How to Create the Next Facebook: Seeing Your Startup Through, From Idea to IPO (7 page)

Read How to Create the Next Facebook: Seeing Your Startup Through, From Idea to IPO Online

Authors: Tom Taulli

Mobile users are also increasingly using their devices for social networking, so it should come as no surprise that mobile usage on Facebook has surged. By the first quarter of 2012, the site had more than 500 million monthly active users for its mobile products.

However, Facebook has struggled with developing mobile products, which thus far have tended to be relatively slow and are packed with too many features. Why is Facebook still struggling with these issues? It could be because Facebook’s DNA is that of a Web-based company that focuses on users’ desktop experience. Creating an engaging interface for the mobile environment is a whole different ballgame. Success in mobile is not a matter of just slapping a Web app on a mobile device; rather, you have to understand how to create a strong mobile experience for your users.

It should not be a surprise, then, that Facebook plunked down $1 billion for Instagram, a fast-growing mobile photo app that had begun to threaten Photos, a key component of Facebook’s business. Instagram, which is an example of a company with a primary focus on the development of its mobile app (also known as a mobile-first company), understands that when it comes to mobile, simplicity is even more important than it is with desktop apps. When Kevin Systrom and Michel Krieger created Instagram, they first brainstormed all the problems they had with existing mobile photo-sharing apps—and there were many. From there, they wanted to solve three of the most frustrating problems they could come up with:

- Mobile photos don’t look so good. They often seemed to be washed out, most likely because of poor lighting. People wanted better quality pictures from their phones without having to be a professional photographer.

- The uploading process for pictures was too long.

- It was not easy to share photos across multiple social networks like Facebook and Twitter.

Once Systrom and Krieger had narrowed their focus and identified only the most pressing problems with mobile photo sharing, it was much easier to come up with the solutions to these problems. (Funny enough, it usually is harder to find the problems with an existing structure, not the solutions!) To address problem number one—picture quality—they created filters that made the pictures look beautiful and almost as if they were retro 1970s photos. As for problem number two—upload speed—the duo built the app

so it would process the upload while users were doing other things on the app, like filling out photo captions. To improve problem number three, they simply sought to understand and integrate more completely the various platforms into their app.

Instagram launched on October 6, 2010, and it was a runaway hit. By the end of the year, it had reached 1 million registered users. In April 2012, when Facebook agreed to buy the company, it had increased its head count to 30 million registered users. Although Instagram’s success is undoubtedly remarkable, it is even more so when you consider that there are hundreds of thousands of mobile apps available for download, making it extremely difficult for any one app to stand out from the rest of the crowd.

If you’re intent on breaking out in the mobile app arena, there are some best practices to keep in mind. Perhaps the most important is to enter into an app category that is known to be habit forming, like photo and video sharing or games, to hook your users and keep them coming back to engage with your app again and again. Speaking of categories, if your app doesn’t fit neatly into one of the available categories on the app store, try to reposition it so that it does. Otherwise, marketing your app may prove extremely difficult. Last, although your app need not be overly simplistic, it should focus on a single function. If you include too many pages, too many features, too much complexity, you will most likely lose users’ interest; so, make your app instantly easy to understand and use. Often, this means sticking to the standards of your chosen app development program, which—as an added bonus—should make it easier for your app to sail through the approval process!

Although the concept of a

stealth startup

—a startup that is working on its product in secret—sounds cool and may work for some types of businesses, such as high-end corporate networking technologies, it is often a bad idea for companies that are developing consumer Internet and mobile apps. After all, it is crucial to get user feedback on your product early on. Instagram’s Systrom calls the process of beta testing your product the “bar exam,” which consists of going to a bar and showing people your app. By observing their reactions, you can gain some valuable insights about your product.

Beta testing proved critical for Instagram. Its first mobile app, Burbn, allowed users to check in to different places, but when they saw that it wasn’t gaining much traction in the marketplace, Systrom and Krieger set out to find out why. After talking to their users about Burbn’s features, Systrom and Krieger realized a common theme kept recurring in their conversations with users: The app’s photo-sharing feature was quite popular. The good businessmen

that they are, Systrom and Krieger decided to abandon Burbn and focus on developing their photo-sharing feature into a full-blown app; as a result, Instagram was born.

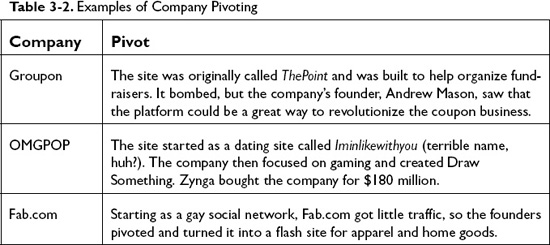

In essence, Systrom and Krieger pivoted, which is another word for when a company abandons its original product and moves into another category. Not long ago, pivot would have been another word for failure, but in today’s world, in which the costs of starting a business are much lower, it is possible for a company to make a radical shift in its product strategy or business model. In fact, investors have even come to expect these types of moves. Instagram is not the only company to arise from a successful pivot.

Table 3-2

outlines a few other notable pivots of which you might not be aware.

Keep in mind that after a pivot, it is important to maintain an insane amount of focus on your product when you develop something that strikes a chord with users. Constant pivoting is a strategy that is likely to go nowhere—and your investors will likely go elsewhere.

For tech entrepreneurs, it is easy to become a slave to the virtual world. But doing so can limit your venture. Hey, people like playing in the real world, too. Look at the kids (and the adults!) who have tons of fun at Disneyland. Or how about a wine tasting tour in Napa? Or a great vacation to, say, Antarctica?

When brainstorming a new business concept, don’t forget to keep the real world in mind, because companies that meld elements of the virtual and real worlds are already gaining traction in the marketplace. Take Birchbox, for example. The founders, Katia Beauchamp and Hayley Barna, got the inspiration

for their company while they were students at Harvard Business School. They wanted to have a way to access a selection of great beauty products, but because of their demanding work schedules and studies, they did not have the time to source the products themselves. Birchbox solves that problem. For $10 a month, members receive a box filled with samples of beauty products based upon their preselected interests. All in all, Birchbox has turned into a great experience for its members and the beauty companies that supply the samples. The service has grown at a rapid pace. Originally, cosmetic companies were finding it difficult to leverage Internet technology to market and sell their products, because it is important for consumers to see, smell, and use their products before making a purchasing decision. With Birchbox, this problem is solved.

In this chapter, we’ve seen how success in product development is really the result of solving one or two big problems that your customers have. How do you do that? Think about some of the problems that have frustrated you personally and then set out to solve them for others. It’s important to understand, though, that it is not a good idea to spend too much time building your solutions. The real value is in getting your product to market quickly so that you can start receiving valuable feedback from your early adopters. In a way, a good product is never really completed; it is always evolving. In the next chapter, we take a look at a hot topic—funding. Even if your product takes off, you still need outside capital to make sure it is built to last.

The lack of money is the root of all evil.

—Mark Twain

In a market where speed is critical, outside funding allows young companies to move faster than they otherwise could if they had to rely only on their own revenues to fund product development. Sure, receiving outside funding means you’ll have to give up some of your company’s equity, but over time, the early sting you might feel when sacrificing a percentage of your shares to get your company up off the ground and running will diminish. If you create a valuable company, the initial dilution of your shares is worth it in the end. Even wealthy entrepreneurs often raise capital. What better way is there to determine whether something you have created is valuable than finding someone who is willing to write a check to fund it?

As we saw in

Chapter 2

, Mark Zuckerberg made some major blunders with his initial attempts at seed funding Facebook. His original investor, Eduardo Saverin, ultimately froze the company’s bank account! However, Zuckerberg learned from the experience and later wound up raising $2 billion from private investors in an effort that proved critical to Facebook’s success. But how, exactly, do you go about securing seed funding? Do you just call up a wealthy friend and ask for an infusion of cash? In this chapter, we take a look at the different types of investors you might want to approach, the cycles of funding, and some helpful tips on timing your funding efforts.

The costs of starting up a company have declined substantially during the past few years, at least for those in the web and mobile app spaces. After all, most mobile or web products can be hosted, launched, and distributed easily and

inexpensively on cloud services such as Amazon Web Services, thereby eliminating the hassle and potential expense of self-distribution. You can start easily with a small amount of storage and bandwidth, and, as your business begins to grow, pay for additional capacity as the need arises. This pay-as-you-go approach is the hallmark of cloud computing and makes life much easier for the startup entrepreneur.

So, for the most part, then, the “cost” of a tech startup is the time it takes for the team to code the product. Your out-of-pocket expenses will likely be well under $25,000, much of which will go toward your company’s legal fees. This is in stark contrast to the dot-com boom of the 1990s, when it took $5 million to $10 million just to obtain vital components of tech infrastructure, such as Oracle databases, licenses to servers, and hardware. All of this is to say that although you may think you need to raise millions of dollars to launch and develop your product successfully, odds are that you will need far less capital than you might expect.

If your product gains momentum, then you are in a much better position to pique the interest of investors whose cash infusions will help you scale your company, which means to accelerate the growth rate. You should also be able to get a better valuation on whatever funding deal you strike with them. Don’t think that you have to draft an executive summary or a business plan when you are still in the early stages of developing your product to draw in investors. Rather, focus on speed and on developing some critical features that will solve your customers’ problems. In many cases, success is the by-product of pursuing a project that solves a specific problem you have. As was mentioned in

Chapter 3

, Zuckerberg created Facebook because he wanted a better way to connect with his school friends, and things turned out pretty well for him.

If your product is getting traction in the marketplace, then the time has come to seek out investors. Keep in mind that there are many types of investors you can approach, each of which specializes in a specific phase of the financing cycle of a new company. Read on to learn about the main players.

Angel investors are those who invest their own money in early-stage ventures. For the most part, angels are wealthy and meet the U.S. Securities and

Exchange Commission’s requirements to act as accredited investors. In addition, many angels have started their own companies or are executives; so, as an added bonus, they often bring incredibly valuable business experience to a venture. Don’t be alarmed if you encounter angels who wish to make their investment in your company through a legal structure, such as a trust or an LLC. Angels use such structures because they lower taxes and provide liability protection, not because they’re trying to scam you.

You may also talk to so-called

superangels

, or high-profile entrepreneurs, who carry a lot of clout within the startup community and become serial investors in early-stage ventures. It’s not unheard of for superangels to invest upward of $1 million in the ventures they decide to seed. In many cases, superangels invest money on behalf of other angel investors by creating a micro venture capital fund. Some examples include Jeff Clavier’s SofTechVC and Chris Sacca’s Lowercase Capital.

Although venture capital is thought of as a fairly new industry, its roots go all the way back to the 1940s, and it started gaining momentum as early as the late 1970s, when VCs funded breakout companies such as Genentech and Apple (keep in mind that VC is a broad term and refers to both a firm and the partners). It was during this time that some of today’s most iconic VC firms, such as Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia, got their start.

Many of these operators set up their offices along Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park, California, which to this day remains the epicenter of venture capital. It is a boon to budding entrepreneurs that Sand Hill Road runs along Interstate 280, which connects San Jose and San Francisco, and is in close proximity to Stanford University. Furthermore, because so many firms are concentrated in such a small area, it is relatively easy and inexpensive, travelwise, to pitch to VCs. An entrepreneur can easily pitch to four or five VCs in a single day!

Unlike angels and superangels, VCs invest money on behalf of their investors, who are known as

limited partners

and include institutions, such as endowments, insurance companies, and pensions, as well as wealthy individual investors (usually, former entrepreneurs). In this respect, a VC is essentially a money manager; any given firm has several partners that seek out investment opportunities, structure investments, and provide follow-on funding.

Every few years, a VC firm will invite several of the firm’s investors to combine their capital into one large fund to invest in an array of startup companies. Each fund that a VC firm creates lasts for 10 to 12 years, which, ideally, is just enough time for the firm to sell all its equity stakes in its portfolio companies. However, because it is now taking much longer for companies to go public—in

part because founders want to retain more control over their ventures, but also because it is very expensive to pull off an IPO—more and more VCs are extending their funds’ lifetimes.

The partners in a venture fund generate income from two sources. First, they charge a management fee, which can range from 1.5% to 2.5%, and is based on the size of the assets in the fund and is paid every year until the fund is closed down. For the most part, the management fee is meant to help the partners with their overhead costs. For a large fund, however—say, $1 billion or more—management fees can turn into lucrative compensation for the partners.

The second way in which the partners of a venture fund are compensated is via carried interest, also known as carry, which generally amounts to 20% to 25% of the profits from the fund and is paid out as a performance incentive. Again, a partner working at a large fund can command substantial fees from carried interest. For example, suppose a VC fund generates $1 billion in profits. In this case, the fund’s partners will divvy up $200 million to $250 million, which explains why many VCs drive fancy cars and have multiple homes.

The VC game, however, isn’t exactly a surefire way to rake in heaps of money. It can be brutal. Because the majority of investments a VC makes will be wipeouts, firms need to invest in ventures that can ultimately become franchise companies, such as Facebook. The goal is that these huge winners will more than compensate for the many losers in a VC’s portfolio. Unfortunately, however, this isn’t always the case. Although tier 1 operators have been able to generate standout returns in recent years, the majority of firms have posted lackluster returns since 2000. As a result, there has been substantial attrition in the number of VC firms in operation throughout the years.

As companies grow larger, it can become more difficult for them to innovate, despite how essential it is for them to do so. Often, in lieu of hiring a chief innovation officer or trying to innovate from within, an established company makes what are known as

strategic investments

in early-stage ventures with the goal of gaining valuable insights into new technologies or markets. Strategic investments can even be used as a way to stifle the competition. For example, a key reason that Microsoft invested in Facebook was to prevent Google from taking a stake in the company; the investment documents that Microsoft drew up specifically prohibited Facebook from taking money from the search engine giant. However, Microsoft received other important benefits when it invested in Facebook. As part of the deal, Microsoft was given the green light to sell

banner ads on Facebook outside the United States, splitting the revenue with the young startup. It also gave Microsoft the opportunity to learn the nuances of social networking. Oh, and the investment turned out to be a big gainer.

So, why should a startup take money from a strategic investor? One reason is that valuation negotiations with strategic investors are usually straightforward, because strategic investors in general are looking for company synergies and not necessarily a substantial monetary return on investment. A strategic investment can also be a validator and vote of confidence for a young company, which can make it easier for the startup to attract new customers. Last, a startup can leverage its strategic investor’s infrastructure and distribution channels, potentially leading to wider exposure and more opportunities for growth. For a startup, it is important to establish specific deliverables—in other words, benefits that the strategic investor will provide, such as introductions or promotion assistance—when brokering a deal with a strategic investor to maximize the value received from the investment.

No doubt, there are downsides to strategic investment, the most notable of which is exposing you to the need to navigate through corporate bureaucracy. It might be agonizingly slow to get much feedback or traction from your strategic investor; therefore, try to avoid giving your strategic investor a board seat or veto rights on major decisions. You should also try to avoid negotiating any exclusive partnerships with your strategic investor because these can ultimately limit your company’s growth potential.

To avoid issuing too many shares and running the risk of diluting their stock, which has the potential to wind up in the wrong hands, many startups seek out debt financing, which involves borrowing money. This may seem like a strange strategy for an early-stage company, but debt financing is actually a viable option for new ventures, thanks to recent developments in startup funding.

During the past decade, a variety of top venture lenders have emerged whose financing provides startups with working capital and helps them buy equipment or meet their short-term needs. If you think only a desperate or flailing startup would seek out venture lenders, think again; Facebook actually borrowed money from venture lenders, such as WTI and TriplePoint Capital, as recently as 2009, when the company’s credibility and worth were already well established.

Prior to signing a debt-financing deal with a startup, venture lenders establish the term of the loan, which usually ranges from 2 to 4 years. Then, in return for their willingness to front the startup working capital, the venture lenders

gain competitive interest on the loan—perhaps 5% to 7%. However, venture lenders also want to acquire some equity in the startup as a condition of the loan. As a result, the startup issues its venture lender an agreed-on number of shares through a warrant, which is similar to a stock option in that it gives the investor the right to buy shares at a fixed price for up to 10 years. The worth of the warrant is usually expressed as a percentage of the overall amount of financing the venture lender provides. For example, if a company borrows $1 million from a venture lender and the warrant coverage is 10%, then the warrant allows the lender to buy $100,000 of common stock. For the most part, venture lenders only provide debt financing to startups that are backed by venture capital, because doing so provides some level of safety for the loan.

Private equity funds, hedge funds, and mutual funds, from time to time, provide late-stage funding for startups they deem to be promising. By investing in more mature companies, late-stage funders have the opportunity to gain strong returns from their investments, but with a significantly lower level of risk because the startups that survive to this later point have most likely achieved impressive sales and established their worth in the marketplace. On the flip side, for the company that is seeking it, late-stage funding is usually a way to generate secondary sales and to allow its existing shareholders—whether they are investors or employees—to sell some of their holdings to these funds. It is also a way to infuse liquidity into the startup without having to file for an IPO, which can be expensive and disruptive to the startup’s operations.