Howzat! (24 page)

Authors: Brett Lee

The bowler gets the credit for the wicket for methods 1–5.

A batter can retire – and is considered not out. He might be injured and unable to complete his innings. If he gets better, he can come back in at the fall of a wicket.

There is a very mysterious eleventh way to be given out. It’s if you retire by agreement with the opposition captain, perhaps to give another batter

on your team a hit. If the retired batter doesn’t go back in, the scorecard would say ‘retired – out’. A player in Pakistan, playing in the Quaid-e-Azam Trophy for Karachi against Pakistan Combined Services in the 1958-59 competition, was hit on the chest by a delivery. He died on the way to hospital. There’s a rumour that the scorecard looked like this:

1st innings: Abdul Aziz, retired hurt, 0

2nd innings: Abdul Aziz, did not bat, dead, 0

This could be a twelfth way of recording a dismissal, but the rumour is untrue. The official scorecard showed the player as ‘absent’.

NDERARM BOWLING

In the early days of cricket, all bowling was underarm. There was fast bowling, slow bowling, spin bowling and lobs, where the bowler tried to land the ball on top of the stumps, but it was all underarm bowling. Female cricketers of the 19 century wore wide skirts and couldn’t bowl underarm because of the dress. So instead, they bowled with a roundarm style.

People watching quickly realised what a powerful technique this was. The ball could be delivered more quickly and the pitch could be used to extract bounce and turn. It was banned for a while but people realised the game was more exciting with this

style of bowling. Roundarm bowling soon turned into overarm bowling. This all happened about 150 years ago—well before the first

Wisden

was published!

The most famous underarm delivery was bowled by Trevor Chappell in a one-day game for Australia against New Zealand in 1981. New Zealand needed six runs off the last ball to tie the game, so the Australian captain, Greg Chappell, told his younger brother to bowl an underarm delivery—a grubber that rolled along the pitch and would be impossible to hit in the air. The New Zealand batter, Brian McKechnie, blocked it, then threw his bat away in disgust. After this, underarm bowling was banned from all grades of cricket.

IGHTWATCHMEN

A nightwatchman is a lower order batter who comes in to protect a higher order batter, usually because a wicket has fallen near the end of the day’s play. Rather than risk losing another wicket in the final few overs, the captain sometimes decides to send in one of his bowlers. His job is just to survive until stumps. He will hopefully be not out and remain in overnight—which is where the term comes from.

Nightwatchmen are not really meant to make big scores—often they are dismissed early the next day. But if they survive the evening, they have done their job.

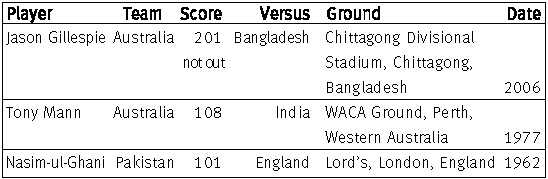

There have been some famous nightwatchmen scores. The highest-ever score by a nightwatchman was made by Jason Gillespie for Australia against Bangladesh at Chittagong in 2006. He made a massive 201 not out.

Here are the best nightwatchmen scores:

Alex Tudor made 99 not out for England against New Zealand in 1999 at Edgbaston.

W

HAT ARE THE ASHES

?

The word ‘Ashes’ comes from a fake obituary written by an English reporter after Australia defeated England in the first Test match the Australians played in England against a full-strength English side, in 1882.

This is what he wrote: ‘In affectionate remembrance of English cricket, which died at The Oval, 29th August, 1882. Deeply lamented by a large circle of sorrowing friends and acquaintances, RIP. NB. The body will be cremated and the Ashes taken to Australia.’

England’s mission was to bring back the ‘Ashes’ from their tour of Australia later that year. They lost the first Test match but won the next two, and so brought the ‘Ashes’ home.

The Ashes trophy is actually a little urn containing what many people believed to be the remains (or ashes) of a bail that was burnt at the time. But in 1998 it was revealed that the ashes in the urn were from a veil, not a bail!

The urn is now kept in the cricket museum at Lord’s, along with the original scorecard from the 1882 game.

VERALL

…

England and Australia have played 311 Test matches since the first game in 1877. The first nine matches played between Australia and England were not for the Ashes. Australia have won 126 of these games (41 per cent), England have won 97 times (31 per cent) and there have been 88 draws (28 per cent). There have been no ties. Three of the games were washed out without a ball being bowled.

OME BIG NUMBERS

…

- The highest team score was made by England at The Oval in 1938, when the team scored a whopping 7 declared for 903.

- The highest individual score by a player in an Ashes Test was 364 by Sir Leonard Hutton during the same game. It was also the highest score in Test history, a record that stood for 20 years.

- Seven players for England have scored double hundreds. Walter Hammond did it four times!

- Fifteen players have made a score of 200 or more for Australia. Don Bradman achieved this feat eight times.

- Jack Hobbs scored 12 hundreds in Ashes Tests – the most by an English player.

- Don Bradman scored 19 hundreds in Ashes Tests – the most by any player.

- There have been some massive partnerships, but the biggest-ever Ashes partnership was between Bill Ponsford and Don Bradman at The Oval in 1934. They put on 451 runs for the second wicket. This is the second-biggest-ever batting partnership for the second wicket in all Tests and the fourth-biggest partnership of all time in Test matches.

- The best bowling figures in one innings were recorded by Jim Laker at Manchester in 1956. He took 10 for 53. In Australia’s first innings he took 9 for 37 – giving him match figures of 67.6 overs, 27 maidens, 19 wickets for 90 runs.

- The most wickets ever taken in a series is 46 – at an average of 9.6 per game. This was by Jim Laker during the 1956 Ashes series played in England.

- The bowler who has taken the most wickets during England and Australia Test matches is the Australian Dennis Lillee. He took 167 wickets, with an average of only 21. (On average, he would get a wicket after every 21 runs hit off him!)

- The most successful wicketkeeper in Australia v England Test matches is Australia’s Rodney Marsh, who took 141 catches and 7 stumpings for a total of 148 dismissals.

B

RADMAN

– 300

IN A DAY

…

1930

A team scoring 300 runs in a day is a pretty good return. That’s 100 runs per session; not that far off a run a minute. Well, what if one batsman did it all by himself? That’s what Don Bradman did on 11 July 1930, at Leeds in England. By the end of the first day, Bradman had made an astonishing 309 runs (not out) out of a total of 3/458. He was dismissed the following morning for 334. His innings lasted 383 minutes and he hit 46 fours.

OTHAM BLITZES AUSSIES

1981

Not once, but twice Ian Botham blitzed Australia during the Ashes series of 1981 – first with the bat, and then with the ball. In the third Test match at Headingley, England followed on 227 runs behind Australia’s first innings total of 401. They quickly

stumbled to 4/41 before Ian Botham blasted a massive 149 not out to give England a chance. Australia only needed 130 runs to win and were looking good at 1/56, but wickets tumbled and eventually England dismissed Australia for 111.

In the fourth Test at Edgbaston, Australia needed 151 runs to win the match. This time it was Botham with the ball who went on to destroy Australia, taking 6 for 37 off 20 overs, including an amazing spell when he took five wickets for just one run!

HATCHER OUT – LBW ALDERMAN

!

1989

Terry Alderman, the Aussie quick from Western Australia, was getting everyone out during the 1989 series in England. He took 42 wickets during the six-Test series – an average of seven wickets per game. Margaret Thatcher was the British prime minister at the time. Someone wanted her out of the job, so spray-painted ‘Thatcher Out!’ on a wall. The next morning the graffiti looked like this: ‘Thatcher Out! – lbw Alderman.’

ORDER

/T

HOMMO

–

SO CLOSE

!

1982

There are two occasions when amazing last-gasp efforts were made by Aussie players to turn certain defeat into almost impossible victory – almost! It was the MCG, 1982, when Allan Border and Jeff

Thomson came together during the final session, with Australia needing 74 runs for the last wicket to snatch a win. They batted for the rest of the day, then into the following morning, bringing the nation to a virtual standstill during the dramatic final moments. Over the course of the partnership, the batters refused to run at least 20 easy singles. After adding 70 runs, and now only four runs short of victory, Thomson edged a ball into the slips. Chris Tavare spilt the ball but it bobbed upwards and Geoff Miller held the catch.

EE

/K

ASPROWICZ

–

SO, SO CLOSE

!

2005

In 2005, during the second Test, England were on the brink of victory. Australia had only two wickets left and still needed 107 runs to win. Brett Lee and Shane Warne, who trod on his wicket, and then Lee and Michael Kasprowicz, almost got there. Steven Harmison finally dismissed Kasprowicz, although some feel that the ball brushed his glove when his hand was off the bat, and so he should not have been given out. In what will be remembered as one of the great acts of sportsmanship, instead of celebrating the win, Flintoff went over to console Lee.

HY DIDN’T HE GET 20?

1956

Taking five wickets in an innings is a fantastic achievement. Nowadays, bowlers hold the ball aloft to the crowd to acknowledge their support just as a batter raises his or her bat after scoring 100 runs. But what about taking 10 wickets? All 10 wickets? Jim Laker, for England, did it in 1956. In the first innings, he didn’t do too badly either, taking 9/37! I wonder if Jim got to keep the match ball?

HAT’S NOT AN AVERAGE – THAT’S A CRICKET SCORE

!

1989

Before the Australian tour of England in 1989, Steve Waugh hadn’t scored a Test 100. By the end of the tour, he had an average of 126.5. In the first Test he made 177 not out and, in the second, an unbeaten 152. It took until the third Test for him to be dismissed – he made a measly 64. His average at that point for the series was a whopping 393.

Thursday 10.00 a.m. to 6.00 p.m.

(1.30—2.10 p.m. lunch)

(4.00—4.20 p.m. tea)

(Likely batting order)

Jimbo Temple

Cam Derwent

Callum White

Sean Robinson

Scott Craven

Kyle van de Brun

Jaimi Clayton

Hanif Khan

Wesley Osbourne

Greg Mackie

Barton Rivers

12th man Jeremy Taylor-Smith

Players to meet in the Frank Grey-Smith Room at 9.00 a.m.

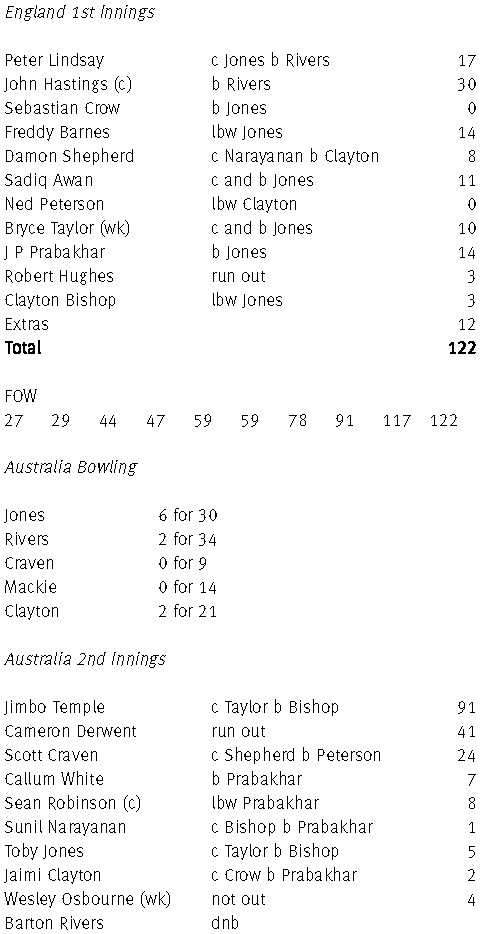

Australia v England

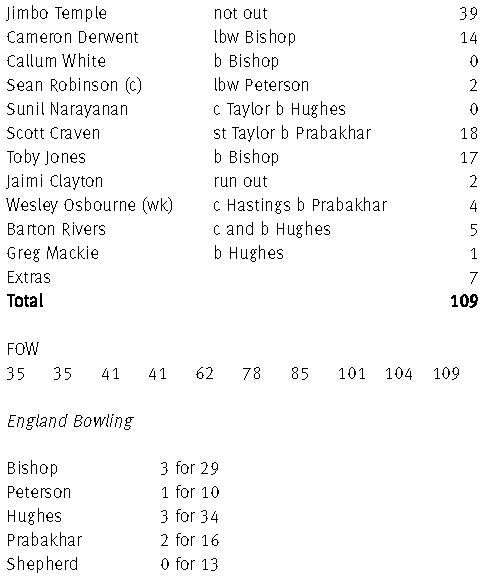

Australia Ist Innings