Hugo! (30 page)

Authors: Bart Jones

Despite lacking the support of Chávez's MBR-200, which was

holding hard to its abstention campaign, Arias won. Two months later,

he moved into the same governor's mansion he had seized during

the February 4, 1992, coup. He was now in charge of the state that

accounted for at least half of Venezuela's economic output with its oil,

minerals, and cattle.

The Bolivarian movement spent a year debating whether Chávez

should run for president. They held local assemblies, regional assemblies,

national assemblies. Often the sessions started in the morning

and lasted into the middle of the night. While many of the Bolivarians

supported the idea, Chávez also faced resistance. Some segments

opposed the electoral route and "accused us of having abandoned the

revolution because we had discontinued the armed struggle . . . We

knew taking the electoral path was a strategic decision that could be

catastrophic, that we could walk right into the trap that the system set

for us, that it could lead us into a pit of quicksand." It was possible

Chávez would not have an adequate electoral machine in place and go

down in defeat, destroying his political aspirations.

But he wanted to take the risk. By early April 1997 he was telling

reporters the MBR-200 would probably put up a candidate — with

Chávez the obvious choice. On April 19, the anniversary of Venezuela's

declaration of independence, he and the Bolivarian movement convened

a special national congress to make a final decision. After a

meeting that started about 9 A.M. and ended about 2 A.M. the next day,

they decided to launch Chávez's candidacy. They thought too much

was at stake. Not only the

presidential race but regional and municipal

elections nationwide were to take place the same day. Not everyone supported

the decision. Some key members of the movement who opposed

the campaign resigned.

Three months later, in July, Chávez officially

registered his new

party, the Fifth Republic Movement (MVR), with the National Electoral

Council. He and his supporters had to change the name of their group

because Venezuelan law prohibited the use of Simón Bolívar's name for

political parties.

Two thousand supporters cheered Chávez outside the board's

offices that day. El Comandante was embarking on a road that would

make him famous worldwide and a force to reckon with. But the international

media hardly noticed. They made brief mention of the developments,

or ignored them. Even those that did report Chávez's candidacy

dismissed it as almost irrelevant. "Few Venezuelans think the retired

lieutenant colonel has a serious chance of winning, since his once sky-high

popularity has plummeted . . . Critics say he talks too much about

South American independence hero Simón Bolívar and too little about

concrete solutions to the country's problems, such as unemployment,

poverty and corruption." One report cited a recent poll giving Chávez

8 percent of the vote.

Instead of the former coup leader, the establishment's eyes were

fixed on

Irene Sáez.

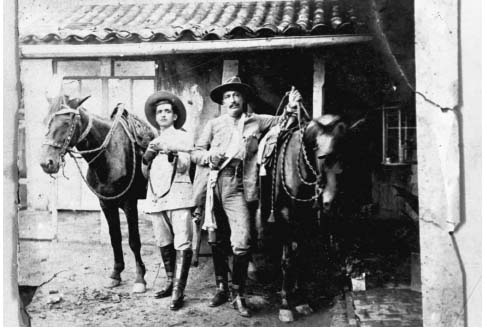

Hugo Chávez and his brother Adán in their

hometown of Sabaneta.

Chávez grew up half believing his greatgrandfather

Pedro Pérez Delgado (on the

right), also known as Maisanta, was a bloodthirsty

outlaw. But a book by a Barinas doctor

and his own investigations later revealed

another depiction of Maisanta, who became

one of his heroes.

As a cadet in Venezuela's military academy with a growing admiration for Simón Bolívar, Chávez was

chosen for a special trip to Peru in 1974 to mark the 150th anniversary of the battle of Ayacucho. The

sojourn provided his first direct exposure to a social experiment launched by a progressive, although dictatorial,

military man, General Juan Alvarado Velasco. Chávez, third from right, enjoyed a dinner out with

other cadets from around Latin America.

Besides delving into the life of Simón Bolívar, Chávez found time for a plethora of activities as a cadet

and young officer, including serving as master of ceremonies for beauty pageants. This one took place

in 1975 during his final year as a cadet.

Chávez holds a Venezuelan flag during a ceremony at a plaza in Barinas in 1976.

Chávez on a training mission in 1982.

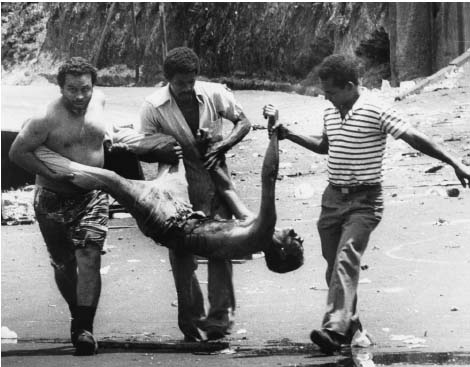

The Caracazo food riots on February 27, 1989,

and subsequent repression by government

troops left more than one thousand people

dead and galvanized Chávez and his Bolivarian

comrades into action. Three years later, they

emerged from secrecy and launched a coup

against the man who ordered the repression,

President Carlos Andrés Pérez. (Francisco

Solorzano)

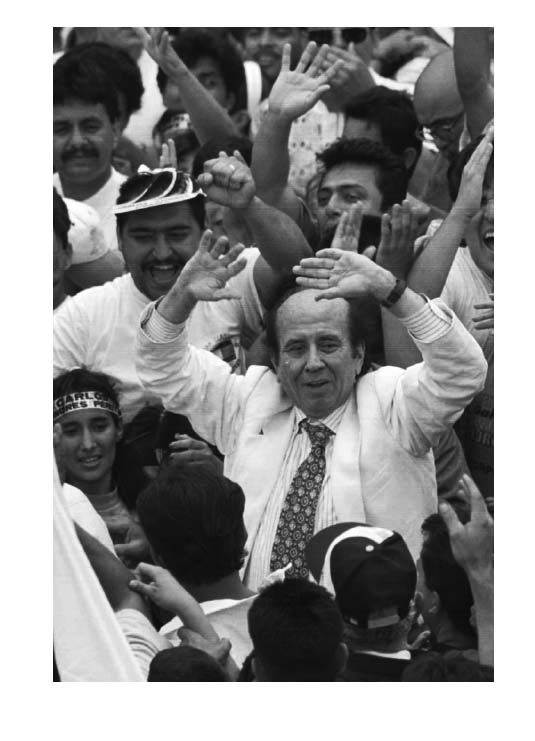

In his heyday President Carlos Andrés Pérez

could make women faint at rallies, but he

became despised after the bloodshed of

the Caracazo, one of the worst massacres

in modern Latin American history. Yet even

after the killings and his impeachment as

president, his home state of Táchira remained

a bastion of support. In 1996, fans mobbed

him. (AP/ Wide World Photos)

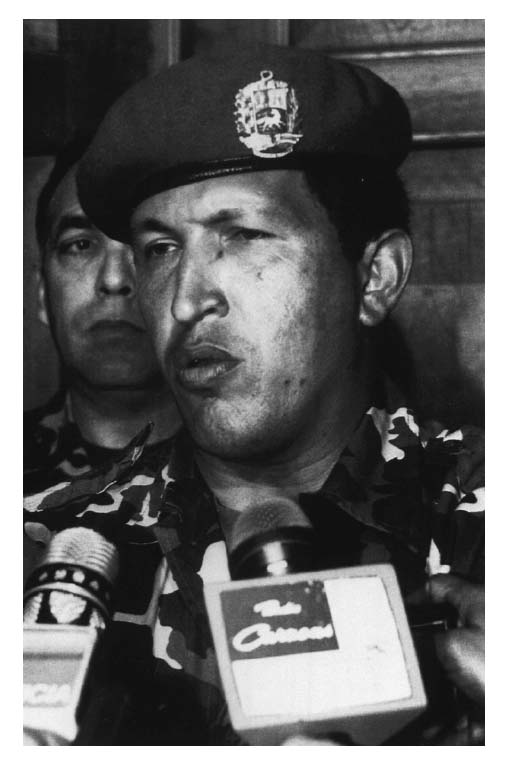

Chávez, then a lieutenant colonel, shocked

the nation by leading a coup on February 4,

1992, and became a hero to millions for trying

to overthrow President Carlos Andrés Pérez.

His famous seventy-two-second speech,

in which he declared live on national television

that the rebels had not achieved their

goals

por ahora,

for now, catapulted him to

stardom. Still, Venezuela's traditional political

class was horrified by the revolt, and foreign

governments condemned it. (AP/Wide

World Photos)