Hugo! (31 page)

Authors: Bart Jones

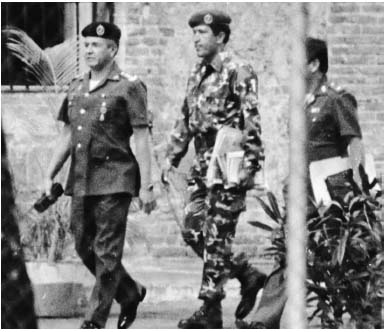

A day after the coup, photographers caught a

glimpse of military officials transferring Chávez

at the Fort Tiuna military base. Ever the voracious

reader, he carried that day's newspapers

and other material. (AP/ Wide World Photos)

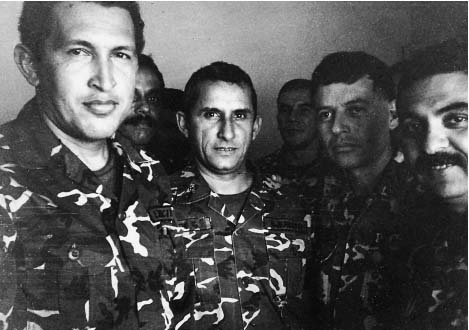

Rather than villains, Chávez, Francisco Arias

Cárdenas (second from right) and other rebels

were seen by many Venezuelans as dashing

heroes while they spent two years in prison

for launching the coup. Newspaper reporters

and photographers were able to sneak in with

their equipment and photograph the rebels in

heroic, wholesome-looking poses.

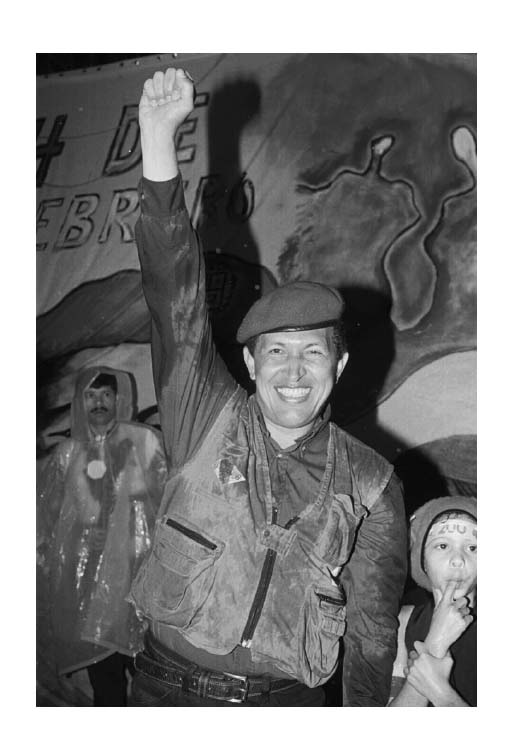

After his release from prison in 1994,

Chávez hit the road to drum up support for

his Bolivarian movement. Far from apologizing

for the coup, he celebrated it. In 1997,

while still debating whether to turn to electoral

politics in Venezuela's corruption-ridden

system, he marked the fifth anniversary of

the uprising by holding a rally in Caracas.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

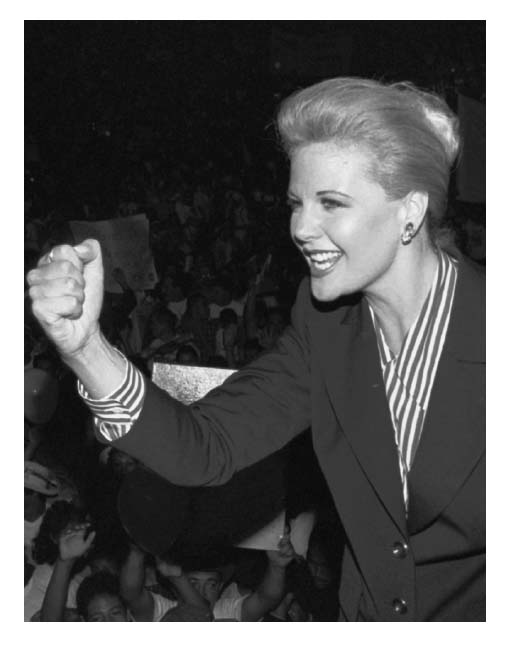

Former Miss Universe Irene Sáez, a six-foot-

one strawberry blonde who had a successful

run as mayor of an upscale section of

Caracas, was the odds-on favorite to win the

1998 presidential race — until she started

opening her mouth and gushing platitudes.

Chávez, in contrast, came soaring in from

out of nowhere — at least in the eyes of the

establishment — and catapulted to the top

of the polls with his fiery calls for revolution.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

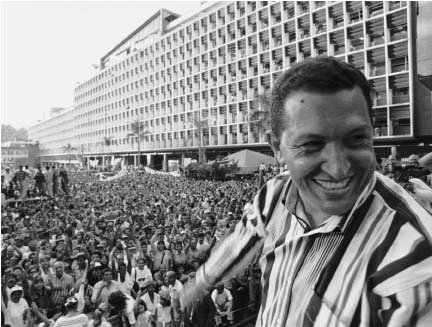

Political analysts, diplomats and pollsters didn't give Chávez a chance of winning in early 1998, but

before long he was attracting massive crowds. When he asked people at this rally to raise their hands if

they agreed with his 1992 coup attempt, a sea of hands went up. (AP/Wide World Photos)

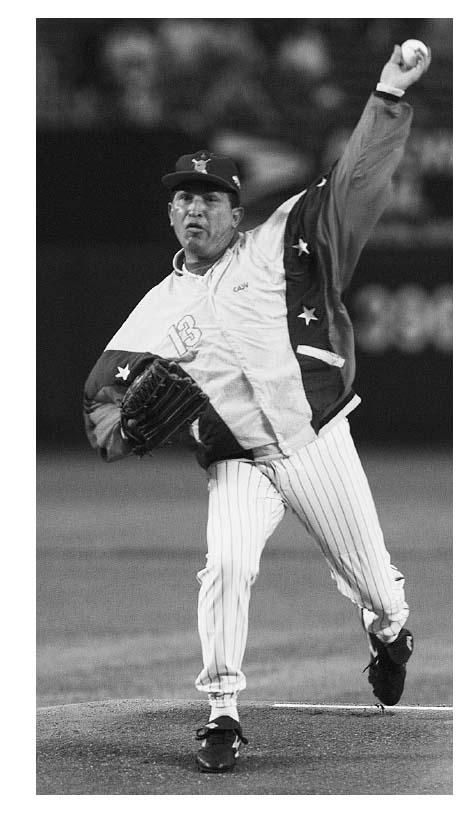

As a boy, Chávez dreamed of playing major

league baseball. He never made it, but

achieved the next best thing in 1999, when

as Venezuela's newly elected president he

threw out the first ball at a New York Mets

game at Shea Stadium. Chávez took the Big

Apple by storm, seducing Wall Street investors

and providing play-by-play commentary

for Venezuelans back home during the game.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

Ever the master of the spontaneous, unpredictable

gesture, Chávez left bodyguards and

businessmen accompanying him on a trip to

China in October 1999 breathless as he took

off jogging up the Great Wall of China. Chávez

later disarmed Vladimir Putin by dropping

into a karate stance when they first met to

show he knew the Soviet leader was a black

belt. (AP/Wide World Photos)

A master communicator, Chávez quickly

sought to exploit his talents by starting

his own weekly, live radio program,

Hello,

President

. Before long he expanded the

Sunday program to television, and by 2007

turned it into a two-night-a-week affair. (AP/

Wide World Photos)

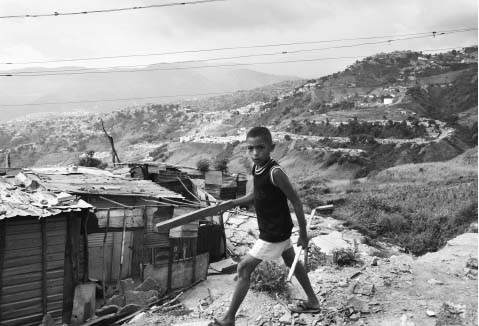

While Venezuela's upper-class despised and

mocked Chávez, the massive underclass

worshipped him. In dirt-poor barrios such

as Nueva Tacagua, where North American

Maryknoll missionaries worked and residents

lived in tin shacks, Chávez was a demigod.

People hung portraits of him on their walls

and vowed to defend him to the death. (Noah

Friedman-Rudovsky)

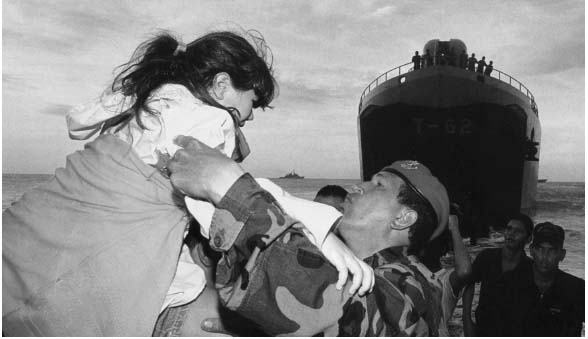

Mudslides in December 1999 on the Caribbean coast near Caracas left an estimated fifteen thousand

people dead in the worst natural disaster in Venezuela in at least a century. Yet in many ways it was one

of Chávez's finest hours as president. He took personal command of the rescue and recovery operation in

Vargas state, gave nightly updates to the mourning nation on television, and barely slept. The navy sent in

ships to pull thousands of people out of the disaster zone. (Agencia Bolivariana de Noticias)

Three days after the tragedy struck, Chávez personally gave instructions to paratroopers before they

were sent into the disaster zone. (Agencia Bolivariana de Noticias)