Human Remains (48 page)

The novel is told from the perspectives of both Colin and Annabel and, movingly, the dead. What made you decide to structure it in this way?

I wanted to experiment a little more with narrative voice, having used a past-present narrative structure in both

Into the Darkest Corner

and

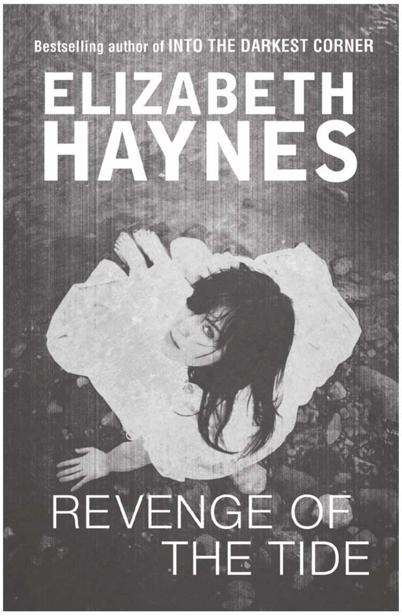

Revenge of the Tide

. I also liked the idea of the roles of predator/prey and hunter/hunted and I thought it was interesting that Annabel and Colin take both roles at different points in the story. Having researched articles, stories and films about those who decide to withdraw from society and end up dying alone, I wanted to explore the potential reasons why people make this choice – and to consider our responsibility as a society to find that balance between caring for our neighbours, and recognising our right to make adult decisions for ourselves as individuals. It’s difficult to know whether dying in your own home, alone, and at a time of your choosing, is something that should be seen as a tragedy or as a basic human right.

Did you enjoy conjuring up Colin’s voice? Do you think he has any redeeming qualities?

It was without doubt a challenge for me to write a male voice, and more specifically one that is so unusual. Without wishing to sound unhinged myself, it took me a long time to persuade Colin to ‘open up’ and let me write his story. It was particularly daunting because he’s clearly far more intelligent than I am and I’m sure he wouldn’t consider me to be equal to the task. Despite his idiosyncrasies, I find his unrelenting confidence in his own importance quite funny.

How did you come up with his particular technique?

There are elements of many different therapies or systems at play in Colin’s technique, all of which are fundamentally designed to be therapeutic or empowering. What Colin does is subtly twist things so that what people actually want – to die without pain or fear – is accomplished in such a way that he can also benefit. One of the principles underpinning neurolinguistic programming is that it needs to benefit both the practitioner and the individual with whom rapport is built – in other words, win-win. Despite his unusual desires, and his undeniable lack of integrity, Colin’s technique still achieves this to a certain degree.

Do you think it could be possible in reality for someone like Colin to use benign therapies for evil intent?

NLP is a powerful way to approach communication, and at its best can be empowering, helping people to change their lives for the better, to encourage them to take control of their own destinies and realise their goals. Whether a combination of NLP, hypnosis and mind control could achieve what Colin does in my story is another matter. Colin’s technique is only successful with those who have already chosen a particular path, after all.

Do you think there is such a thing as an untraceable murder?

No, but it’s endlessly intriguing to try and imagine one. Everything leaves a trace – the trick is knowing where to look.

This is your third novel; how does it differ from

Into the Darkest Corner

and

Revenge of the Tide

?

The first two books are fundamentally about relationships, so I wanted to write a book about the absence of them, about people existing in the world and revolving around the wider society like satellites – living as part of the system but not connecting with it. I am intrigued by the idea of loneliness – or, more accurately, aloneness – as a lifestyle choice.

How did you decide on the structure for

Into the Darkest Corner

?

I wanted to write a dual narrative to explore the story of the same character four years apart, to show the difference in her life before and after a traumatic event. In

Into the Darkest Corner

we meet Catherine as a carefree and outgoing twenty-something, living her life to the full, but we also see her four years later, clearly suffering from crippling OCD and terrified for her safety. Running the two strands of her story in parallel allowed the contrast to unfold, from how she copes with Christmas, for example, to more essential themes such as her opinion of herself; her courage, her fears, her self-esteem. And the structure provided the perfect way to build suspense, since the reader is waiting to find out what happened to Catherine in between those times, and whether her fears in the present are justified after all.

When we meet Genevieve in

Revenge of the Tide

she’s living on a houseboat on the River Medway. What made you choose this setting for the novel?

I’ve always been intrigued by the idea of living on a boat, and as I live quite close to Rochester and the River Medway I thought it would be a great place to write about. I really enjoyed threading Genevieve’s adventure through locations that are familiar to me; it made the whole story much more real. The river can be so beautiful in the sunshine, with Rochester Castle standing guard over it, but at night time, on a foggy night in November, it can be quite chilling too. For Genevieve, at the start of the novel, living on a houseboat is a long-held dream, but it rapidly turns into a nightmare when a body washes up against the side of her boat, and she recognises the victim. The story of how she came to escape her double-life in London – office worker by day and pole dancer by night – is revealed as her sense of security in her new life unravels, and the boatyard that initially felt like such a safe haven can’t hide her secrets forever.

How has your life changed since the publication of your first novel,

Into the Darkest Corner

?

It’s all gone a bit mad, really. I have to keep pinching myself, since the life I’m living now is pretty close to the writerly fantasies I had as a teenager. I did think I’d rather like to live in a converted lighthouse on a clifftop, but for now I’m quite happy with my writing shed. I particularly enjoy meeting book groups, in person or via Skype. It’s a real privilege to get feedback from readers and I’m always amazed and chuffed to bits when people take the time to email to let me know what they thought. I still can’t quite believe that I am a writer and I struggle to call myself that if anyone asks what I do for a living. I can manage to think of myself as a novelist – as is everyone who successfully completes National Novel Writing Month! – but being a proper writer somehow still seems a little unreal, as though the day I take that on board will be the day it all ends. For now, though, I’m going to enjoy everything while I can.

If you have enjoyed

Human Remains

, you might also like Elizabeth Haynes’ bestselling second novel

Revenge of the Tide

For an exclusive extract, read on…

I

t was there when I opened my eyes, that vague feeling of discomfort, the rocking of the boat signalling the receding tide and the wind from the south, blowing upriver, straight into the side of the

Revenge of the Tide

.

For a long while I lay in bed, the sound of the waves slapping against the hull next to my head, echoing through the steel and dulled by the wooden cladding. The duvet was warm and it was easy to stay there, the rectangle of the skylight directly above showing the blackness turning to dark blue, and grey, and then I could see the clouds scudding overhead, giving the odd impression of moving at speed – the boat moving rather than the clouds. And then, that discomfort again.

It wasn’t seasickness, or river-sickness, come to that: I was used to it now, nearly five months after I had left London. Five months living aboard. There was still a momentary shock when my feet hit the solid ground of the path to the car park, a few wobbly steps, but it was never long before I felt steady again.

It was a grey sort of a day – not ideal for the get-together later, but that was my own fault for planning a party in September. ‘Back to school’ weather, the wind whistling across the deck when I got up and put my head out of the wheelhouse.

No, it wasn’t the tide, or the thought of the mismatched group of people who would be descending on my boat later today. There was something else. I felt as though someone had rubbed my fur the wrong way.

The plan for the day: finish the last bit of timber cladding for the second room, the room that was going to be a guest bedroom at some point in the future. Clear away all the carpentry tools and store them in the bow. Sweep out the boat, clean up a bit. Then see if I could cadge a lift to the cash-and-carry for party food and beer.

There was one wall left to do, an odd shape, which was why I had left it till last. The room was full of sawdust and offcuts of wood, bits of edging and sandpaper. I’d done the measurements last night but now, frowning at the bit of paper, I decided to recheck it all just to be on the safe side. When I had clad the galley I’d ended up wasting a load of wood because I misread my own measurements.

I put the radio on, turned up loud even though I still couldn’t hear it above the mitre saw, and got to work.

At nine, I stopped and went back through to the galley for a coffee. I filled the kettle and put it on to the gas burner. The boat was a mess. It was only occasionally that I noticed it. Glancing around, I scanned last night’s takeaway containers hurriedly shoved into a carrier bag ready to go out to the main bins. Dirty dishes in the sink. Pans and other items in boxes sitting on one of the dinette seats waiting to be put away, now I had finally fitted cupboard doors in the galley. A black plastic sack of fabrics and netting that would one day be curtains and cushion covers. None of it mattered when I was the only one in here, but in a few hours’ time this boat would be full of people, and I had promised them that the renovations were almost complete.

Almost complete? That was stretching the truth a little thin. I had finished the bedroom, and the living room wasn’t bad. The galley was done too, but needed cleaning and tidying. The bathroom was – well, the kindest thing that could be said about it was that it was functional. As for the rest of it – the vast space in the bow that would one day be a bigger bathroom with a bath instead of a hose for a shower, a wide conservatory area with a sliding glass roof (an ambitious plan, but I’d seen one in a magazine and it looked so brilliant that it was the one project I was determined to complete), and maybe a snug or an office or another unnamed room that would be wonderful and cosy and magical – for the moment, it worked as storage.

The kettle started a low whistle, and I rinsed a mug under the tap and spooned in some instant coffee, two spoons: I needed the caffeine.

A pair of boots crossed my field of vision through the porthole, level with the pontoon outside, shortly followed by a call from the deck. ‘Genevieve?’

‘Down here. Kettle’s just boiled, want a drink?’

Moments later Joanna trotted down the steps and into the main cabin. She was dressed in a miniskirt, with thick socks and heavy boots, with the laces trailing, on the ends of her skinny legs. The top half of her was counterbalanced by one of Liam’s jumpers, a navy blue one, flecked with bits of sawdust and twig and cat hair. Her hair was a tangle of curls and waves of various colours.

‘No, thanks – we’re off out in a minute. I just came to ask what time we should come over later, and do you want us to bring a lasagne as well as the cheesecake? And Liam says he’s got some beers left over from the barbecue, he’ll be bringing those.’

She had a bruise on her cheek. Joanna didn’t wear make-up, wouldn’t have known what to do with it, so there it was – livid and purplish, about the size of a fifty pence piece, under her left eye.

‘What happened to your face?’

‘Oh, don’t you start. I had a fight with my sister.’

‘Blimey.’

‘Come up on deck, I need a smoke.’

The wind was still whipping, so we sat on the bench by the wheelhouse. The sun was trying to make its way through the scudding clouds but failing. Across the other side of the marina I could see Liam loading boxes and carrier bags into the back of their battered Transit van.

Joanna fished around in the pocket of her skirt and brought forth a pouch of tobacco. ‘The way I see it,’ she said, ‘she should keep her fucking nose out of my business.’

‘Your sister?’

‘She thinks she’s all clever because she’s got herself a mortgage at the age of twenty-two.’

‘Mortgages aren’t all they’re cracked up to be.’

‘Exactly!’ Joanna said with emphasis. ‘That’s what I said to her. I’ve got everything she’s got without the burden of debt. And I don’t have to mow any lawn.’

‘So that’s what you were fighting about?’

Joanna was quiet for a moment, her eyes wandering over to the car park where Liam stood, hands on his hips, before pointedly looking at his wristwatch and climbing into the driver’s seat. Above the sounds of the marina – drilling coming from the workshop, the sound of the radio down in the cabin, the distant roar of the traffic from the motorway bridge – the van’s diesel rattle started up.