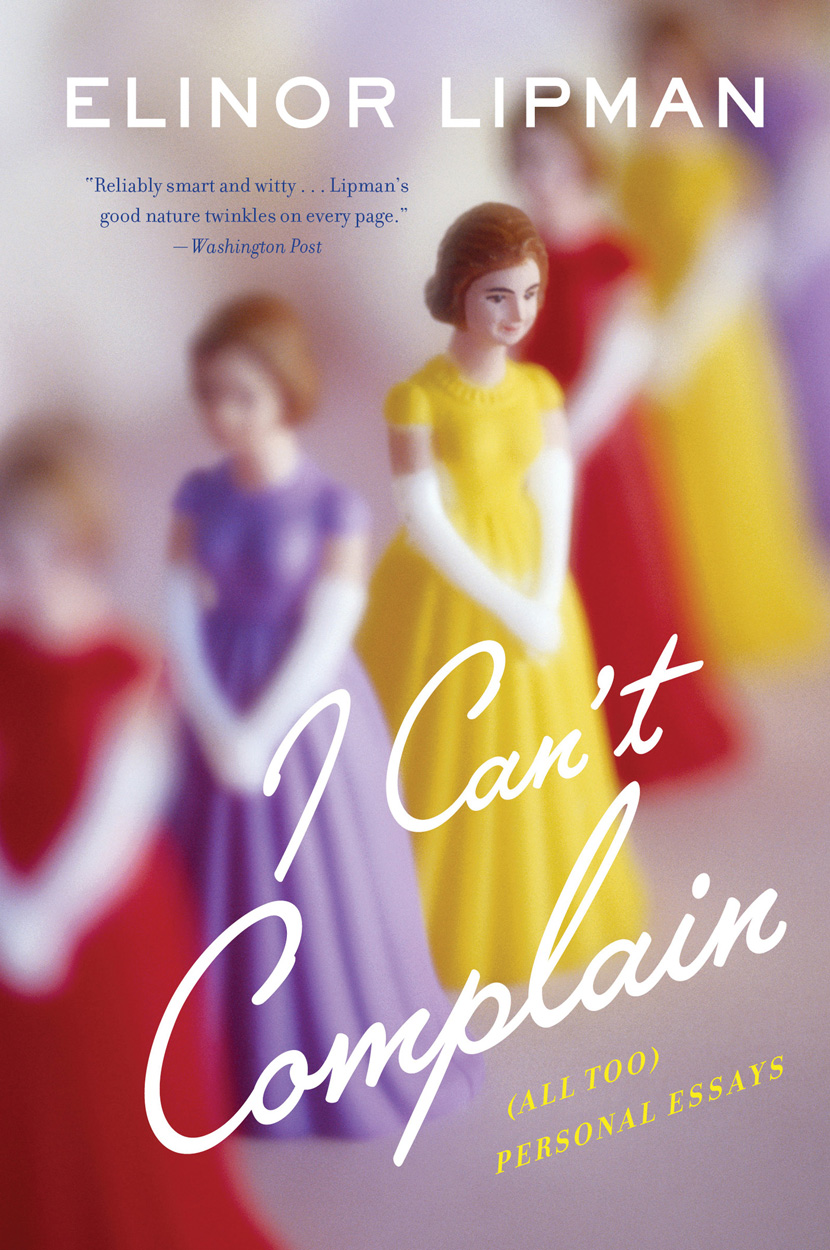

I Can't Complain

Authors: Elinor Lipman

The Rosy Glow of the Backward Glance

A Tip of the Hat to the Old Block

No Outline? Is That Any Way to Write a Novel?

Assignment: What Happens Next?

Your Authors’ Anxieties: A Guide

Watching the Masters by Myself

First Mariner Books edition 2014

Copyright © 2013 by Elinor Lipman

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Lipman, Elinor.

[Essays. Selections]

I Can’t Complain : (All Too) Personal Essays / Elinor Lipman.

pages cm

ISBN

978-0-547-57620-6

ISBN

978-0-544-22790-3 (pbk.)

I. Title.

PS3562.I577I25 2013

814'.54 — dc23

2012040360

e

ISBN

978-0-547-57622-0

v2.0314

For Benjamin Austin,

champion son

I came late to the essay-writing genre, when various magazine and newspaper editors asked me to expound on a particular topic and I felt it was not only polite but also good deadline discipline to say yes. Before too long I discovered that which often starts out as duty can, a thousand words later, become an assignment I was awfully glad to have accepted.

I was inspired to write “How to Get Religion” after attending Julia Flora Reilly Golick’s bat mitzvah in 1993—so amazed and touched was I by every minute of that event. Its last line (“I pray you invite me to your wedding”) came true, a most satisfying follow-up.

I must thank Laura Mathews of

Good Housekeeping,

who faithfully and regularly asks me for nonfiction, especially for her Blessings column. “Good Grudgekeeping” appeared there under (obviously!) a different title.

I am particularly grateful to the

Boston Globe

for not tiring of my byline. It was John Koch who gave someone at their magazine the idea to put me into a new Coupling column rotation, which resulted in “Boy Meets Girl,” “May I Recommend . . . ,” “I Want to Know,” “A Mister and Missus,” “Monsieur Clean,” “Ego Boundaries,” “I Married a Gourmet,” “I Sleep Around,” and “The Best Man,” hence the 750-word uniformity.

“A Tip of the Hat to the Old Block” was a

Boston Globe

op-ed piece that ran on St. Patrick’s Day 2008. Don MacGillis edited all of my op-ed pieces there, so lightly that I will always recognize him as a genius. “I Still Think,

Call Her”

ran in the

Boston Globe Magazine

on January 1, 2000, and “Assignment: What Happens Next?” in the

Boston Globe

as “Carrie Me Home: To Big or Not to Big?”

“Confessions of a Blurb Slut” appeared originally as “A Famous Author Says ‘Swell! Loved It!’” in the

New York Times’

Writers on Writing column (their title—who’d say that about herself?) and was then reprinted in

Writers on Writing,

volume 2.

Ages ago, when Amazon.com sold only books, Kerry Fried asked me to write about my favorite novel.

The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis,

crazy-funny stories by Max Shulman, was my answer. Here, in “The Funniest and the Favorite,” I’ve grafted to it part of an essay I wrote about my father for

Good Housekeeping,

“Father Knew Best.”

“It Was a Dark and Stormy Nosh” was published in

Gourmet;

“I Touch a Nerve” in

Tablet Magazine;

“We ❤ New York” in

Guilt and Pleasure;

“My Book the Movie” on the Huffington Post; and “No Thank You, I Think” in

More

magazine. “Julia’s Child” was written for the anthology

What My Mother Gave Me: 31 Women Remember a Favorite Gift,

so thank you, Elizabeth Benedict, its editor, and Algonquin Books. In a different form, I wrote about my mother’s condiment phobia in

Salon

(“Mayo Culpa”).

“No Outline? Is That Any Way to Write a Novel?” first appeared on Borders’ website. “Which One Is He Again?” was originally published in the

Washington Post

’s Book World section, as was “Your Authors’ Anxieties: A Guide,” for which I thank assigning editors, respectively, Marie Arana and Ron Charles, increasingly viral (in the best sense) book lover.

“This Is for You” originally appeared in the

New York Times

’ Modern Love column as “Sweetest at the End.” It remains one of my most gratifying publishing experiences, the gift that keeps on giving, for which I thank the column’s editor, Daniel Jones.

“Watching the Masters by Myself” was originally published in the

Southampton Review

after its editor, Lou Ann Walker, asked me to contribute to the journal’s issue on water. When I confessed I had nothing to say about water, she most kindly said, “Then write about anything you want.”

“A Fine Nomance” is published here for the first time.

My son barely minds being publicly exposed in several of these essays and seems to think it goes with the territory. “The Rosy Glow of the Backward Glance” was originally published in

Child.

Even more embarrassing for him, “Sex Ed” appeared in the anthology

Dirty Words

(Bloomsbury, 2008). Thank you, Ben, over and over again.

As with everything I write, Mameve Medwed and Stacy Schiff were these essays’ first readers and counselors. Thank you, dear friends. And thank you, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, for letting me do this, with deep and fond thanks to Andrea Schulz, ideal editor.

And to Robert Austin, of blessed memory and star of the show.

Julia’s Child

T

HERE ARE SEVERAL

things I know by heart, requiring no notes or source material, mostly along practical, gastronomic lines: you add a fistful of dried split green peas and a parsnip to the water that will become your chicken soup; you don’t overbeat the milk and eggs lest your custard not set; and when making latkes, you always grate the onion before the potatoes so the glop doesn’t turn pink.

I don’t know what other daughters learned from their mothers, but mine was a purveyor of homely domestic tricks, imparted not with formal lessons but by osmosis, by example at the stove, in conversation, as dough was kneaded or liver chopped.

First, what you should know about Julia Lipman: She married late, at thirty-seven, but when asked by her daughters how old she was when she married answered twenty-three. She gave birth to me, the second child, six weeks before she turned forty-one. My birth certificate lists “mother’s age” as thirty-four, and it wasn’t a clerical error. She was dainty. She wore housedresses and aprons and never flats. Her bed slippers were mules, and her French twist required hairpins. She used Pond’s cold cream on her face, Desert Flower lotion on her hands, and she didn’t like drinking water out of mugs. She loved the Red Sox and mild-mannered British mysteries. She wore Estée Lauder perfume and never the colors red, pink, or purple. She did not drive a car, play tennis or golf, ride a bicycle, know how to swim, nor did I ever see her pitch, throw, or catch a ball. She was a queen of arts and crafts: a Brownie leader, a Lowell Girls Club fixture for twenty-five years; a knitter, sewer, wallpaperer, and gardener extraordinaire.

I wanted to be like my father, who was neither dainty nor fussy in any department. He scraped mold off leftovers and burnt crumbs off toast, while saying cheerfully, “Just doing my duty.” I once heard him say, “Julia, what saves you is that slight streak of crudity running through you,” meaning the occasional off-color remark she’d murmur that made them both laugh. I once found a petal-shaped piece of earring, sapphire-blue glass, in her dresser drawer, and asked her what it was. “Oh, it’s from an earring I once had. Daddy stepped on it and broke it when we were dating,” she told me. They had met in December and married in March, thirty-seven and thirty-nine years old. A stranger had once stopped her on the street, an older man who asked, “Why is it that someone with a complexion as beautiful as yours isn’t married?”

I’m sure she said nothing; I’m sure she shrugged and said, “Oh, I don’t know.”

But my sister and I and our children, given the opportunity from within a time capsule, might have said to the gentleman, “It probably didn’t hurt her skin one bit that she had a condiment phobia.”

You see, before there were conspicuous vegans, before the era of lactose intolerance and sprue, when the description “picky eater” referred only to toddlers and children, my mother was famously finicky. I don’t mean,

If someone served her a hamburger with ketchup, she’d scrape it off and eat it nearly uncontaminated.

What I mean is: If some unfortunate hostess put ketchup on the bun, my mother would push the offending plate away, unable to eat the accompanying potato chips, and ask for nothing else, her appetite ruined. And maybe eat a shirred egg when she got home. It was like our mother had a condition. She refused to taste anything that came from the grocery aisle displaying the vinegary and the savory, the relishes, the mustards, the pickles of any kind; the salad dressings, the barbecue sauces, the Tabascos, the Worcestershires or the A.1.’s. We didn’t even own them. If a visiting relative needed some such lubricant or flavor enhancer, he knew not to ask.

Maybe there are worse things. I am no fan of ketchup. I eat my French fries plain, my fried clams without tartar sauce, and my Reubens without Russian dressing. My favorite mustard is the powdered kind, ground from the seed. Ditto my sister.

Now I feel bad. Our mother wanted us and loved us dearly. Her chicken and fish, her stews, her meatloaves, her lasagna and kugels and everything else were flavorful in their own, unadulterated way. Spices and herbs were fine. Lemon juice was a dear friend. She could cook and bake like Julia Child, undaunted by recipes calling for yeast or buttermilk or breast of veal. She made a lemon meringue pie that a food stylist would envy. She baked challah, Irish bread, cinnamon rolls, babka, Christmas stollen for neighbors. I have these recipes on index cards, half in her handwriting and half in mine. She sewed us beautiful clothes—prom dresses of piqué and velvet, and impossible little miniature outfits for our Ginny dolls.

By her standards, I was not a purist. I once looked up from my lunch of marinated leftover cooked vegetables and found her watching me with a puzzled look.

“What?” I asked.

She shook her head sadly. “I never thought a daughter of mine would like cold food so much.”

Her children were food adventurers, she thought. She asked me why I needed to dribble balsamic vinegar on a fresh tomato when it was so delicious plain. I countered, “Do you butter your bread? Do you salt your tomato? It’s like that, Ma.” I know I scared her, once confiding that a squeeze of ketchup added just the right

je ne sais quoi

to my minestrone. And my college roommate’s mother-in-law’s recipe I make every time an occasion calls for a brisket? Ketchup again. But never when my mother was visiting. I never tricked her. I used some other tomato reduction. A daughter-hostess has to live with herself.