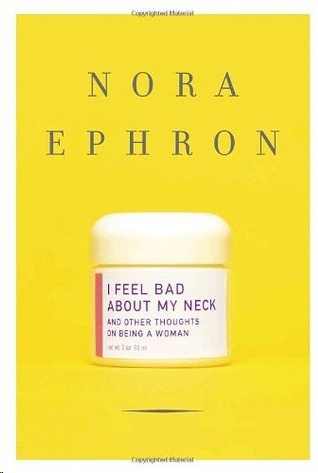

I Feel Bad About My Neck

Read I Feel Bad About My Neck Online

Authors: Nora Ephron

Contents

Me and JFK: Now It Can Be Told

The Story of My Life in 3,500 Words or Less

The Lost Strudel or

Le Strudel Perdu

For Nick, Jacob, and Max

I Feel Bad About My Neck

I feel bad about my neck. Truly I do. If you saw my neck, you might feel bad about it too, but you’d probably be too polite to let on. If I said something to you on the subject—something like “I absolutely cannot stand my neck”—you’d undoubtedly respond by saying something nice, like “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” You’d be lying, of course, but I forgive you. I tell lies like that all the time—mostly to friends who tell me they’re upset because they have little pouches under their eyes, or jowls, or wrinkles, or flab around the middle, and do I think they should have an eye job, or a face-lift, or Botox, or liposuction. My experience is that “I don’t know what you’re talking about” is code for “I see what you mean, but if you think you’re going to trap me into engaging on this subject, you’re crazy.” It’s dangerous to engage on such subjects, and we all know it. Because if I said, “Yes, I see exactly what you mean,” my friend might go out and have her eyes done, for instance, and it might not work, and she might end up being one of those people you read about in tabloids who ends up in court suing their plastic surgeons because they can never close their eyes again. Furthermore, and this is the point: It would be All My Fault. I am particularly sensitive to the All My Fault aspect of things, since I have never forgiven one of my friends for telling me not to buy a perfectly good apartment on East Seventy-fifth Street in 1976.

Sometimes I go out to lunch with my girlfriends—I got that far into the sentence and caught myself. I suppose I mean my women friends. We are no longer girls and have not been girls for forty years. Anyway, sometimes we go out to lunch and I look around the table and realize we’re all wearing turtleneck sweaters. Sometimes, instead, we’re all wearing scarves, like Katharine Hepburn in

On Golden Pond.

Sometimes we’re all wearing mandarin collars and look like a white ladies’ version of the Joy Luck Club. It’s sort of funny and it’s sort of sad, because we’re not neurotic about age—none of us lies about how old she is, for instance, and none of us dresses in a way that’s inappropriate for our years. We all look good for our age. Except for our necks.

Oh, the necks. There are chicken necks. There are turkey gobbler necks. There are elephant necks. There are necks with wattles and necks with creases that are on the verge of becoming wattles. There are scrawny necks and fat necks, loose necks, crepey necks, banded necks, wrinkled necks, stringy necks, saggy necks, flabby necks, mottled necks. There are necks that are an amazing combination of all of the above. According to my dermatologist, the neck starts to go at forty-three, and that’s that. You can put makeup on your face and concealer under your eyes and dye on your hair, you can shoot collagen and Botox and Restylane into your wrinkles and creases, but short of surgery, there’s not a damn thing you can do about a neck. The neck is a dead giveaway. Our faces are lies and our necks are the truth. You have to cut open a redwood tree to see how old it is, but you wouldn’t have to if it had a neck.

My own experience with my neck began shortly before I turned forty-three. I had an operation that left me with a terrible scar just above the collarbone. It was shocking, because I learned the hard way that just because a doctor was a famous surgeon didn’t mean he had any gift for sewing people up. If you learn nothing else from reading this essay, dear reader, learn this: Never have an operation on any part of your body without asking a plastic surgeon to come stand by in the operating room and keep an eye out. Because even if you are being operated on for something serious or potentially serious, even if you honestly believe that your health is more important than vanity, even if you wake up in the hospital room thrilled beyond imagining that it wasn’t cancer, even if you feel elated, grateful to be alive, full of blinding insight about what’s important and what’s not, even if you vow to be eternally joyful about being on the planet Earth and promise never to complain about anything ever again, I promise you that one day soon, sooner than you can imagine, you will look in the mirror and think, I hate this scar.

Assuming, of course, that you look in the mirror. That’s another thing about being a certain age that I’ve noticed: I try as much as possible not to look in the mirror. If I pass a mirror, I avert my eyes. If I must look into it, I begin by squinting, so that if anything really bad is looking back at me, I am already halfway to closing my eyes to ward off the sight. And if the light is good (which I hope it’s not), I often do what so many women my age do when stuck in front of a mirror: I gently pull the skin of my neck back and stare wistfully at a younger version of myself. (Here’s something else I’ve noticed, by the way: If you want to get really, really depressed about your neck, sit in the backseat of a car, right behind the driver, and look at yourself in the rearview mirror. What is it about rearview mirrors? I have no idea why, but there are no worse mirrors where necks are concerned. It’s one of the genuinely compelling mysteries of modern life, right up there with why the cold water in the bathroom is colder than the cold water in the kitchen.)

But my neck. This is about my neck. And I know what you’re thinking: Why not go to a plastic surgeon? I’ll tell you why not. If you go to a plastic surgeon and say, I’d like you just to fix my neck, he will tell you flat out that he can’t do it without giving you a face-lift too. And he’s not lying. He’s not trying to con you into spending more money. The fact is, it’s all one big ball of wax. If you tighten up the neck, you’ve also got to tighten up the face. But I don’t want a face-lift. If I were a muffin and had a nice round puffy face, I would bite the bullet—muffins are perfect candidates for this sort of thing. But I am, alas, a bird, and if I had a face-lift, my neck would be improved, no question, but my face would end up pulled and tight. I would rather squint at this sorry face and neck of mine in the mirror than confront a stranger who looks suspiciously like a drum pad.

Every so often I read a book about age, and whoever’s writing it says it’s great to be old. It’s great to be wise and sage and mellow; it’s great to be at the point where you understand just what matters in life. I can’t stand people who say things like this. What can they be thinking? Don’t they have necks? Aren’t they tired of compensatory dressing? Don’t they mind that 90 percent of the clothes they might otherwise buy have to be eliminated simply because of the necklines? Don’t they feel sad about having to buy chokers? One of my biggest regrets—bigger even than not buying the apartment on East Seventy-fifth Street, bigger even than my worst romantic catastrophe—is that I didn’t spend my youth staring lovingly at my neck. It never crossed my mind to be grateful for it. It never crossed my mind that I would be nostalgic about a part of my body that I took completely for granted.

Of course it’s true that now that I’m older, I’m wise and sage and mellow. And it’s also true that I honestly do understand just what matters in life. But guess what? It’s my neck.

I Hate My Purse

I hate my purse. I absolutely hate it. If you’re one of those women who think there’s something great about purses, don’t even bother reading this because there will be nothing here for you. This is for women who hate their purses, who are bad at purses, who understand that their purses are reflections of negligent housekeeping, hopeless disorganization, a chronic inability to throw anything away, and an ongoing failure to handle the obligations of a demanding and difficult accessory (the obligation, for example, that it should in some way match what you’re wearing). This is for women whose purses are a morass of loose Tic Tacs, solitary Advils, lipsticks without tops, ChapSticks of unknown vintage, little bits of tobacco even though there has been no smoking going on for at least ten years, tampons that have come loose from their wrappings, English coins from a trip to London last October, boarding passes from long-forgotten airplane trips, hotel keys from God-knows-what hotel, leaky ballpoint pens, Kleenexes that either have or have not been used but there’s no way to be sure one way or another, scratched eyeglasses, an old tea bag, several crumpled personal checks that have come loose from the checkbook and are covered with smudge marks, and an unprotected toothbrush that looks as if it has been used to polish silver.

This is for women who in mid-July realize they still haven’t bought a summer purse or who in midwinter are still carrying around a straw bag.

This is for women who find it appalling that a purse might cost five or six hundred dollars—never mind that top-of-the-line thing called a Birkin bag that costs ten thousand dollars, not that it’s relevant because you can’t even get on the waiting list for one. On the waiting list! For a purse! For a ten-thousand-dollar purse that will end up full of old Tic Tacs!

This is for those of you who understand, in short, that your purse is, in some absolutely horrible way, you. Or, as Louis XIV might have put it but didn’t because he was much too smart to have a purse,

Le sac, c’est moi.

I realized many years ago that I was no good at purses, and for quite a while I managed to do without one. I was a freelance writer, and I spent most of my time at home. I didn’t need a purse to walk into my own kitchen. When I went out, usually at night, I frequently managed with only a lipstick, a twenty-dollar bill, and a credit card tucked into my pocket. That’s about all you can squeeze into an evening bag anyway, and it saved me a huge amount of money because I didn’t have to buy an evening bag. Evening bags, for reasons that are obscure unless you’re a Marxist, cost even more than regular bags.

But unfortunately, there were times when I needed to leave the house with more than the basics. I solved this problem by purchasing an overcoat with large pockets. This, I realize, turned my coat into a purse, but it was still better than carrying a purse. Anything is better than carrying a purse.

Because here’s what happens with a purse. You start small. You start pledging yourself to neatness. You start vowing that This Time It Will Be Different. You start with the things you absolutely need—your wallet and a few cosmetics that you have actually put into a brand-new shiny cosmetics bag, the kind used by your friends who are competent enough to manage more than one purse at a time. But within seconds, your purse has accumulated the debris of a lifetime. The cosmetics have somehow fallen out of the shiny cosmetics bag (okay, you forgot to zip it up), the coins have fallen from the wallet (okay, you forgot to fasten the coin compartment), the credit cards are somewhere in the abyss (okay, you forgot to put your Visa card back into your wallet after you bought the sunblock that is now oozing into the lining because you forgot to put the top back onto it after you applied it to your hands while driving seventy miles an hour down the highway). What’s more, a huge amount of space in your purse is being taken up by a technological marvel that holds your address book and calendar—or would, but the batteries in it have died. And there’s half a bottle of water, along with several snacks you saved from an airplane trip just in case you ever found yourself starving and unaccountably craving a piece of cheese that tastes like plastic. Perhaps you can fit your sneakers into your purse. Yes, by God, you can! Before you know it, your purse weighs twenty pounds and you are in grave danger of getting bursitis and needing an operation just from carrying it around. Everything you own is in your purse. You could flee the Cossacks with your purse. But when you open it up, you can’t find a thing in it—your purse is just a big dark hole full of stuff that you spend hours fishing around for. A flashlight would help, but if you were to put one into your purse, you’d never find it.