I Sleep in Hitler's Room (39 page)

Read I Sleep in Hitler's Room Online

Authors: Tuvia Tenenbom

I stop him here. How the heck did the Israelis and the Palestinians sneak into the door of this story? How did the Jews get into the picture? Again!

Why Israelis and Palestinians?

“Why not?”

Why yes? Got nothing better, or worse, to deal with?

“Well, we invited Daniel Barenboim and he wanted it.”

Why him?

“He’s big!”

No other biggies?

“Why not him?”

He’s a political animal, very controversial and sometimes anti-Israel.

“He wasn’t then.”

Really? Do you have the exact history of Daniel, when, how, and where he was when he initiated his political involvement?

No, he doesn’t. And then, after a long and almost endless discussion, the answer I finally get is: “Ask Mr. Kaufman.”

Who the heck is he?

“He was in charge.”

So, you don’t really know why Daniel was invited?

“No.”

Good to know.

Martin might not know, but the facts are these: Daniel Barenboim founded West–Eastern Divan with the famed Palestinian-rights activist Edward Said; the performance in Weimar was the orchestra’s maiden performance.

Martin is also a festival producer. One of the festivals he produces on a yearly basis is the Jüdische Kulturtage (Jewish culture days) in Berlin.

Why you?

“They asked me.”

You’re not Jewish, right?

“I’m not.”

What did you learn about Jews?

“They are all connected. Worldwide. No matter what each of them thinks, no matter what political views each of them holds, they are all connected.”

The Nazis would be happy to hear you say this. They think the same thing.

“No, no! No! This is not what I said!”

What did you say?

“The Jews are spiritually connected. All around the world.”

Really?

“When a Jew meets another Jew, anywhere in the world, they immediately connect. I know this. I saw this. That’s what’s unique about the Jews!”

Good that Martin does the festival. Finally there’s somebody out there who can tell the Jews who they are.

Paul Kernatsch, general manager of the Elephant Hotel, comes to say hello.

“I was born in Ireland. My wife likes to buy shoes and I like the Apple store.”

There you go. We immediately connect.

I ask him to tell me the difference between the eastern Germans and the western Germans.

“Eastern German girls are more beautiful and more open-minded.”

Really?

“Yes!”

Give me an example!

“In the east of Germany, pregnancy is not an illness.”

I am here only one day, but I have this impression, and maybe I am totally wrong, that the eastern Germans don’t take as well to criticism as do the western Germans, and that they’re more stubborn. Am I totally wrong?

“No. Both observations are true.”

This hotel was built, or redesigned, on Hitler’s orders. Is this the only hotel he built?

“As far as I know, yes.”

Tell me, how many people specifically asked to sleep in that room, the way I did?

“Since I’ve been here, thirteen years at this point: two people.”

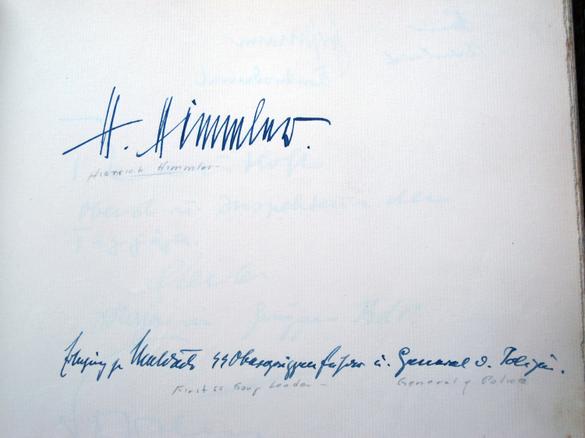

I guess I am in good, exclusive company. Paul goes on to show me the hotel’s guest book from the Nazi period. Here is the signature of Magda Goebbels, wife of Joseph. She writes the date: October 26, 1941. And here’s Heinrich Himmler’s signature, no date given.

Chapter 21

From the Entertainment Center of Buchenwald Concentration Camp to a Demonstration against Israel

Volkhard Knigge, director of Buchenwald Memorial Foundation, shows up at the Elephant. He was told that I was around, and he came for a chat.

“The KZ is the place of rebirth for those who survived and were liberated there. For survivors it’s very important that the sites are kept.”

Why would anyone want a place like that to be preserved? If I cut your limbs off in this room, would you like the room to be preserved?

“I can’t speculate on why the survivors feel this way. This you have to ask them.”

What’s the nature, or the origin, of Nazism?

“It all starts with the definition of a nation. To the French, what defines a nation is its acceptance of a constitution. You are French if you accept the constitution. To the German, it’s blood base. You are a German if your father and mother are.”

The present government of Israel believes that a Jew is a Jew based mostly on blood. Isn’t this, given your definition of the German nation according to Nazism, a Nazi philosophy? In other words: Are those Jews basically Nazis?

Volkhard goes on and on, a custom in this land when you don’t know how to answer a question but don’t want to admit it. But I don’t let go, asking for a clearer response. Being pushed, he says: “I talk about NSDAP [the Nazi party], not others.” But a few minutes later he calms down and we get to exchange some info. He even recommends a bar in Jerusalem, one he really likes: Uganda. Free-minded people are there, he tells me.

Uganda? Why Uganda?

“That’s an allusion to that old idea.”

He refers to the idea that Jews should have settled in Uganda instead of Palestine. Uganda, the bar, made a name for itself as a place that ‘sympathizes with the Palestinian plight.’ Why the director of Buchenwald Memorial gets his hands wet in the Israeli–Palestinian mess is beyond my understanding.

On the next day I meet Daniel Gaede,

Leiter Abteilung Gedenkstättenpädagogik

(head of the education department, concentration camp), at Gedenkstätte Buchenwald. He is to show me around the KZ, and I meet him at the entrance. First off, he tells me he’s partly Jewish. His “grand, or grand-grandfather, was a Jew.” As if I didn’t know. There are more Germans alive with Jewish grandpas than with Nazi grandpas. Way more! But I don’t say anything. Daniel, on the other hand, does. “By Nazi law, I am one-eighth Jewish,” he says. I wonder if Rabbi Schmidt knows how many Jews live in his country.

Daniel takes me on a tour of the camp. Truth is, I’d never come here on my own. But the local tourist-information office in Weimar, the office that takes care of all my needs while I’m in Weimar, arranged this. They heard a Jew was coming, so they arranged for him a KZ visit. And so, here I am.

But I shouldn’t complain. I get to see what the average visitor usually doesn’t get to see. I am on an official visit, and I get an intimate look into a place of horror. And entertainment. Yes, entertainment. What kind of entertainment? A zoo. Yes, there was a zoo next to the crematorium. I would never have known that on my own, but Daniel shows it to me. He actually showed me the crematorium, but I ask him to explain to me a funny-looking structure across a narrow road from the crematorium.

“That’s for the brown bears,” he tells me.

Brown bears? What do brown bears do in a crematorium?

Well, it turns out that the SS had a zoo, right next to the place where humans were turned to ashes, for its soldiers to enjoy. Gassed people on the left, brown bears on the right. Together, they made for one great entertainment center.

We walk into what he calls the pathology room. This Buchenwald concentration camp is actually a theme park, in case you didn’t get it by now. Disneyland in the Fatherland. No kidding. In the room I’m now in, you can see how this place operated. Here is a raised stone structure, with faucet and various cutting tools, where organs were taken out from the dead bodies before the bodies were sent to the crematorium. Sometimes a heart would be taken out for some kind of research, other times skulls were shrunk, to fist-size, and given to friends to serve as ornaments. If the dead had a nice tattoo, the skin and flesh would be cut, dried, and later be made into lampshades. What a life! Lampshades, brown bears, and little skulls as key chains. Good use of dead Jews. All prepared for you by folks with PhDs.

Don’t cry when you read this, my dear, or you’ll never stop.

Down under is the cellar. Here you can see hooks for hanging people.

I stand here, imagine this happening, and find myself speechless.

There’s an elevator here that was used to “ship” the bodies straight into the ovens.

The company that made the ovens, Daniel tells me, felt so elated about their engineering feat that they went on to “register for patent rights.”

The other day, says Daniel, he took a taxi to the camp. He and the driver got to talking. “When I was a boy,” the driver told him, “I used to see corpses in there.”

Yep. The kids were playing around, and they saw everything. It was never a secret. I wonder if this cabbie was ever as honest with his children.

Most likely, not.

After hours of horrific stories, these and others, Daniel sits down with me just outside the campgrounds to tell me about himself and share his thoughts.

He spent a year and a half in Israel, working for Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste, or ASF, Action Reconciliation Service for Peace. His job was to sort documents at Yad Vashem, the Israeli organization dealing with the Holocaust Memorial.

That’s not all he did in Israel. In addition to his work at Yad Vashem, Daniel got involved with the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, spending eight weeks as a volunteer in an Arabic hospital in Nazareth. Nice, right?

Why did you get involved?

“I was there, living the conflict; I was in the middle of it. I wanted to find out if my belief in conflict resolution through nonviolent means was just a great philosophy or something that could also be practiced.”

What did you learn?

“That it’s also practicable.”

How did you figure this out? How did you find that the nonviolence solution is the way?

“Look at this country!”

Germany?

“Yes.”

Hello: This country? You knew this country’s story before you went to Israel, long before you boarded the plane. So why did you go?

Daniel looks at me, apparently surprised that I’m so direct with him.

During his stay in Israel, he tells me, he went to Nablus to talk with the city’s deputy mayor, to learn from him about the Palestinian side; he wanted to understand the Palestinians better. He’s a peace lover, after all. At the end of the meeting, when he and his brother returned to their car, it exploded. What happened? A Palestinian had put a bomb in their car. Daniel’s brother was killed, and Daniel himself lost his left eye.

Was this the end of your involvement in the Israeli–Palestinian issue?

“No. In Weimar last year, I marched in a demonstration for Gaza.”

What has Weimar got to do with Gaza?

“The city of Weimar awarded a human-rights prize to a lawyer from Gaza.”

I step out of my role as interviewer and share a moment with Daniel. I tell him that I totally agree with the notion that he has a right to criticize Israel, demonstrate against it, and do whatever he wishes. That’s the essence of democracy and I have no problem with it. But what I don’t understand is why a person who works in a concentration camp, a system where millions of Jews found their death, doesn’t feel the need to be a little bit more sensitive to Jewish feeling and refrain from such activities.

Daniel listens to me but says not a word. His hands are shaking, and the cup of soda he holds in his right hand almost spills. He stares somewhere, not at me. I push the envelope. I ask him if his hate of the Jew is so deeply rooted that sense has simply failed him. He doesn’t answer. Does he regret anything he did? No.

If the death of his brother and the loss of his own eye didn’t move him, I won’t either.

The story of Israel and Gaza is quite complicated, having many sides to it. But the fact, known to anybody who speaks or reads Arabic, remains this: Gaza has the world’s highest concentration of people who believe in driving the Jews into the sea. Why would anybody from Buchenwald join them?

Because.

At Divan restaurant, a Turkish eatery, there’s a jam session of Yiddishkeit, a Jewish summer festival in Weimar. I go there to spend some time with Jews, living Jews with skulls bigger than fists. Olaf is one of the singers.

Are you Jewish?

“My great-grandmother was a Jew.”

Olaf goes on, telling me his life story. In short, here goes: He studied theology, served as pastor of a church in the Rhineland for a short time, and then went to Berlin, where he still lives. Today he does Yiddish concerts here and there, whenever, but he gets his livelihood from “public assistance.”