I Sleep in Hitler's Room (36 page)

Read I Sleep in Hitler's Room Online

Authors: Tuvia Tenenbom

“Lo,” Oliver answers me in Hebrew. No.

You studied Hebrew on your own?

“Ken,” says Oliver—Yes—and continues the conversation in Hebrew.

“Years back my father came home one day and gave me a gift: The Hebrew Bible. I didn’t know how to read it, didn’t even know where it starts and where it ends. I put it away and forgot about it. When I got involved with a Catholic priest and we became boyfriends, I thought of the book and gave it to him.”

Your boyfriend is a Catholic priest?

“We’re no longer together.”

Well, interesting. But how does he know Hebrew?

“When my father died I was thinking about the gift that he gave me, the Hebrew Bible. I wanted the Bible back, and I got it. I couldn’t read it still. I decided that I had to. I flew to Israel, where I studied Hebrew in an ulpan [language school].”

Oliver inserts an Israeli CD in the bar’s CD player, and the gay bar is now loudly singing in Hebrew.

“I threw two Israeli parties here. Last time, before we had the party, I went to the Jewish community to see if I could borrow a menorah for our party. The synagogue is Orthodox. I got in and the rabbi was in a meeting. I was shaking. Imagine if I went to the archbishop and asked him to lend me a religious item for a gay party. He would show me the door! But here I sit in an Orthodox synagogue, and I am not a Jew, asking them to lend me a religious item for a gay bar. I was shaking. And then the rabbi looks at me and he says: ‘When the party is over, remember to bring it back.’ I couldn’t believe it! We had the menorah right here, in the center!”

Most everybody I met in my German journey up to now was anti-Israel. What’s wrong with you, Oliver?

“People in Germany, the majority of them, don’t understand what it means to worry if you’ll see your son by the end of the day or not, because he might be dead by then. This is the reality for Israelis. I lived there a few months and I saw it. But Europeans don’t get it. Not just Germans. I try to tell them that what happens there is not about politics, it’s about life and a certain mentality. They think everything is about politics, like it is here. But no, over there it’s not about ideas and opinions, it’s about life.

“Do you want a kosher beer? I’ve got them. Want to try one?”

Oliver refuses to be paid for whatever I consume in his bar. “You’re a guest,” he says.

The Jewish Bride of Berlin would feel home in this bar.

On the day of morrow, refreshed and very well fed, I go to see Paul Bauwens Adenauer. Paul is the grandson of Germany’s Kennedy, or at least Köln’s Kennedy, Konrad Adenauer, the first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany and the founder of CDU, or Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands, the Christian Democratic Union of Germany.

Paul is the president of the Chamber of Commerce, Köln, and owns his own company.

Is Germany one nation?

“Soccer-speaking, it is.”

Besides soccer. Is this one country?

“It’s on the way.”

Is there a characteristic, a common trait that unites all Germans?

“Yes.”

What is it?

“The Germans are romantic. They think there’s a solution for everything and anything. If you watch German talk shows, you will see that they think there’s an answer to every question. There’s a belief that the government can solve everything. In the United States they believe in themselves, a feeling of “I can do.” That is not the case here. Here is this belief that somebody, usually government, can and should do everything. This translates into an attitude that, if something I did doesn’t work, it’s never my fault but some other entity’s fault.”

Can this explain World War II?

“In a way. There’s a belief and trust in authority. It’s this feeling that Hitler used and misused.”

Are you telling me that the clichés are truth? Meaning, would you say that Germans like to obey?

“Germans like to follow leadership.”

More so than other nations?

“Yes.”

Paul too?

“What?”

You. You too?

“I hate it. I don’t like to follow, I would—”

So you are not German?

“I am a

Kölsche

. In Köln, people forced the archbishop out of the city gates hundreds of years ago. That’s our history.”

Could it be that the reason you don’t like to obey is that you come from the ruling class? Not everybody in this city is so fortunate, or misfortunate, to have a chancellor as a grandpa.

“Maybe. But I think it’s also what Kölners are. It’s not in their nature for them to follow. They prefer to follow themselves.”

So, they’re not Germans?

“No, they are the worst of the Germans . . .”

What else makes them Germans, then?

“They are good mechanics. And they like to work.”

Why do they like to work?

“I don’t know. They like to work more than they like to make money. Americans like the money, Germans like the work. Germans like to make things perfect. There’s honor in fine work. Germans hate it when something doesn’t work properly.”

Paul strikes me as a smart man. I wonder if I should bring up the “Jew” issue and decide in favor. Perhaps Paul would be able to cure me of my “Jewish Hurt” in this country. I put the issue on the table:

I can report to you that with one exception, in a gay bar, the Germans I met “at random” were all anti-Jewish. Why is it that so many Germans are negative about Jews, Israel?

“I think that this attitude is stronger in other European countries than in Germany.”

Let’s talk about Germany. Is it true that Germans are very critical of Jews and of Israel?

“Now that you put it this way, I think it’s true. I didn’t think of it before, but yes.”

All political alliances?

“The left wing is more critical of Israel than the conservatives are.”

Paul also has an explanation for this attitude:

“Israel must sometimes be tough, I believe, because Israel is such a small country, a little country surrounded by enemies. But the average German doesn’t see this, they think that problems should be solved in a soft way. That’s the German’s response to the history of the Third Reich. They send soldiers to Afghanistan but they think that nobody should be allowed to get hurt.”

How do you explain the anti-Semitism I encountered in, let’s say, Duisburg?

“There are basically no Jews in this country, just a very few. The relationship the people here have to the Jews is theoretical, not real.”

Germans, those who purport to be strongly against anything that even smells of anti-Semitism, were present when I was bombarded with anti-Semitic accusations, but they didn’t contradict any of it. Why didn’t they object?

“Germans follow. They are not people who will stand their ground. They have no political backbone.”

Soon DITIB will have a mosque here. What is your opinion? In Duisburg they send strong Jew-hate messages to their people, even celebrating known anti-Semites. Yes, they do it in Turkish and not in German. But they do it. This is what they really stand for. And soon they’re coming here, to your city, and it’s going to be in your courtyard. What do you do with this?

“Good question.”

Are you embracing the idea of having a mosque here?

“Two thoughts in my head. There is freedom of faith, so why not have a mosque?

But when I hear what you say, this seed, this venom of Jew hating, I think it would be horrible if this grew in Köln. There’s a false understanding of tolerance on the part of the Germans.”

What will you do?

“I will bring it to public awareness.”

After a long discussion, during which he admits to not having a clear answer or a viable path for action, he says:

“In Köln we don’t go deep into these things, just the surface. We like parties . . .” Paul thinks that Köln is the fun city of Germany. “All the lazy people are assembled here. I think that’s what it is.”

Last question: What does it mean to come from the family that you come from?

“I am a slave to my status.”

Minutes after meeting Paul, I sit down with Stefan, a laid-off journalist. This is a man on the other side of cultured Köln: the poor intellectual.

Stefan says, quoting either himself or others: “When the Dom is ready and complete, the world will end.”

This obviously happens to be a fact of life here. The work and reconstruction done on the premises of this Dom is constant. But it’s worth it. A “complete Gothic architecture has two towers. There exists only one structure like it: in Köln.”

Stefan, free from the boundaries that some media companies might require of their employees, lets his tongue loose: “Business and politicians are together. One hand washes the other. This is the biggest mafia in Germany. But Köln isn’t special in that regard; this happens in other cities as well.”

Arnd Henze, on the other hand, has a job. He is a

redakteur

, or editor, at the powerful WDR TV. I meet him next. I take one look at him and I “box” him. He is, I say to myself, a self-proclaimed ethical and moral man, totally PC, a self-righteous man who cares for the weak, the poor, the minority and is totally committed to total human rights. The perfect newsman. The Honest Newsman. If he could, he would choose this woman: An old Jewish black Muslim Buddhist lesbian, who suffers from severe malnutrition and is in the advanced stages of AIDS. I mean, if that were possible.

Let’s talk and see who he really is.

Why are you doing what you’re doing?

“To offer transparency to people and inform them, in order to maintain democracy. Democracy is about participation, and for that you must be well informed. I am aware that as a person I am biased, but my colleagues have their biases as well.”

Greeaat!

Do you have an agenda?

“Of course I do. Human rights, climate protection.”

What’s the ratio of your pushing stories that conform to your political views, in comparison to those that oppose your views?

“I had Bush sound bites that I totally disagreed with.”

Come on! That’s obvious. If I had to report in 1939 what’s going on I would report on what Hitler said. That’s nothing to do with pushing ideas, that’s pure news.

“I didn’t make the comparison to Hitler, you did.”

I am fully well aware of that, and I will never say that you made any comparison between Bush and Hitler. Now: Forget sound bites. Stories. Those that corroborate your views and those that do not. What’s the ratio? How many of the stories that you personally report on happen to be stories that confirm your own views?

“Ninety percent of the feature-length stories that I do corroborate my views.”

He goes on to tell me that WDR’s “ratings go down when we report on the Middle East, because people think that we’re pro-Israel.” I don’t know much about WDR but it’s good to know that this huge media company loves the Jews. Somebody’s got to love them, don’t you agree?

I walk along the streets of Köln, a city that had almost vanished during World War II. My eyes travel over its reconstructed walls and buildings, and I think: How painstakingly the German people must have worked! They’ve restored every little stone, redrawn every old line, and refilled every drop in their faucets. This must have taken unshaken determination, enormous effort, and rivers of sweat. But they did it. Dot by dot, drop by drop, tear by tear. It is admirable, it is touching, and it’s fascinating.

But what does it say about the people?

Who knows?

Continue walking and you will see how cultured this city is. And how ridiculous.

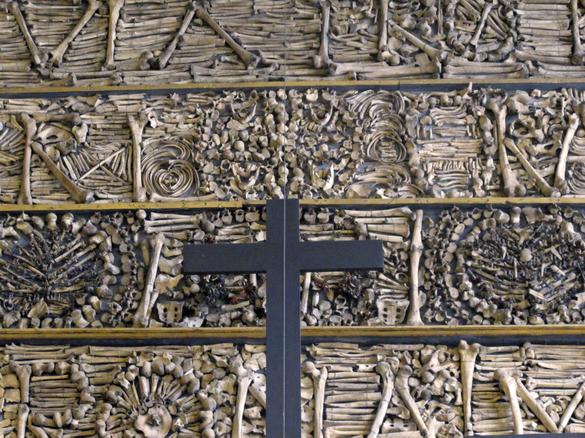

Here is a church, St. Ursula, honoring a virgin who died for the Right Cause with 11,000 of her companions, all virgins as well. Yes, really.

You might wish to say that this is just a legend, but you will risk the wrath of God if you do. No kidding. If you stick around in this church long enough, you will discover in it a section known as the Golden Chamber. Here you’ll find an exhibition of “prayer lines” that are made of human bones. Yep. Human bones, quite a large number of them, painted gold and hung all over in this chamber. All around. It’s a disturbing image. Human bones on the walls that look frighteningly similar to the chicken bones on my plate from the day before. As if these walls in this church are here to teach you: That’s all you are, a chicken for somebody to eat.