Iconoclast: A Neuroscientist Reveals How to Think Differently (13 page)

Read Iconoclast: A Neuroscientist Reveals How to Think Differently Online

Authors: Gregory Berns Ph.d.

Tags: #Industrial & Organizational Psychology, #Creative Ability, #Management, #Neuropsychology, #Religion, #Medical, #Behavior - Physiology, #General, #Thinking - Physiology, #Psychophysiology - Methods, #Risk-Taking, #Neuroscience, #Psychology; Industrial, #Fear, #Perception - Physiology, #Iconoclasm, #Business & Economics, #Psychology

A Minority of One

Although Feynman had no problem with his role as perennial iconoclast, for most people the willingness to stand alone for one’s opinion does not come easily. Like the fear of public speaking we saw in the last chapter, the fear of social isolation is deeply woven into the human brain. We readily discount our own perceptions for fear of being the odd one out.

All our primate cousins, and even the earliest hominids, have depended on their clans for survival. As a result, a million years of mammalian evolution have produced a human brain that values social contact and communication above all else. The way in which we interact with each other is, in many ways, more important than what our own eyes and ears tell us. So much so, that the human brain takes in information from other people and incorporates it with the information coming from its own senses. Many times, the group’s opinion trumps the individual’s before he even becomes aware of it. And while we humans readily ascribe our thoughts and feelings to ourselves the truth is that many of our thoughts originate from other people.

There is, of course, great value in belonging to a group. Safety in numbers, for one. But there is also a mathematical explanation for why the brain is so willing to give up its own opinions: a group of people is more likely to be correct about something than any individual. Both of these factors—social value and the statistical wisdom of the crowd—explain why so few people end up being true iconoclasts. Understanding these effects can encourage would-be iconoclasts and foster conditions for innovation within organizations. The story begins in the 1950s …

The men dress with conspicuous purpose.

9

They have volunteered for a psychology experiment in visual acuity. Most of the men have never taken a course in psychology, sticking instead to a course of study in history, politics, and economics that is well known to the Wall Street recruiters each spring. At the designated time, a group of eight assemble in an ordinary classroom. Most of the men know each other in some fashion, for the campus is one of the smaller of the Ivies. All have been recruited by a friend, classmate, or fraternity brother, but the recruitment process is strictly

sotto voce

, lending an air of mystery to the whole enterprise.

The professor enters the room. Solomon Asch wears a weathered tweed coat over a matching vest and woolen pants. He is shorter than most of the volunteers and points to the two rows of desks. With an

Eastern European accent, he asks the men to please take their seats. There ensues some jockeying of position, but one subject of particular interest ends up in the middle of the second row.

In fact, he is the only subject. The other seven are acting as stooges to go along with the professor’s experiment.

The subject looks up from his desk and sees an artist’s easel holding a stack of white pieces of cardboard. He begins to wonder why he volunteered for this exercise. He had heard about the experiment from a fellow who lived in a neighboring suite of his dorm, but this dorm mate isn’t someone he would call a friend under most circumstances. The other men in the room seem so at ease with themselves, talking about the recent Dewey-Truman fiasco and smoking cigarettes.

Asch clears his throat and explains the task.

“Before you is a pair of cards. On the left is a card with one line. The card at the right has three lines differing in length.” He turns over the first pair of cards to illustrate his point. “They are numbered 1, 2, and 3, in order. One of the three lines at the right is equal to the standard line at the left. You will decide in each case which is the equal line. There will be eighteen such comparisons in all.”

Asch pauses and looks around the room to make sure that his audience understands the task. He takes in this particular group and adds, “As the number of comparisons is few and the group small, I will call upon each of you in turn to announce your judgments, which I shall record here on a prepared form.” The professor points to the person nearest him in the front row and adds, “Suppose you give me your estimates in order, starting here in the first row, proceeding to the left, and then going to the second row.”

The fellow sitting next to the subject plays the part of a wiry, nervous sort. He chain-smokes and fidgets constantly. He raises his hand and asks, “Will there always be a line that matches?”

Asch assures him that there will. “Very well. Let’s begin with the card currently showing.”

The card on the left has a single line, about ten inches long. The right-hand card has three lines, the middle line being substantially longer than the other two and also clearly of the same length as the target.

The first person says, “Line Two is the correct answer.”

Asch marks something down on a clipboard and motions to the second person to answer. The men (actors) proceed around the room until the subject—the only subject—must answer.

The task seems straightforward, and by this point he is somewhat relieved that it isn’t difficult. “Two,” he says.

The second set of cards contains lines that range in height from one to two inches, but as with the first set, it is not difficult to pick out the ones that match. Everyone gives the correct answer.

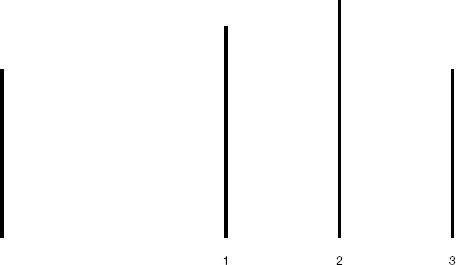

The third set looks like what is shown in figure 4-1.

The first person says, “One. It’s Line One.”

The subject does a double take, and while he regards the lines with renewed intensity, the second person says, “One.” So does the third. And the fourth, and everyone in front of him.

FIGURE 4-1

Asch experiment

The subject becomes intensely aware that the entire group is awaiting his answer. He thinks,

I don’t see how they can answer so quickly. I thought it was Three, but I can see how One might be the same length. My eyes must be going bad

. Feebly, he states, “One.” The fidgety guy lights up another cigarette and takes a long drag, getting immense enjoyment from the drama playing out in the seat next to him.

It does not get any better for the subject. Of the eighteen trials, the group is unanimously wrong on twelve. The unwitting subject, despite what his eyes see, goes along with the group 100 percent of the time.

After the experiment, everyone but the true subject is dismissed. Asch pulls him aside and asks, “How often did you answer as the others did, against your own first choice?” This was a standard question asked of all the subjects. Invariably, even the most conformist of subjects underestimated the number of times that he went along with the herd.

The subject replies, “Possibly as many as one-fourth or one-third.” The subject thinks about his estimate and continues, “Mostly I wasn’t sure, I was undecided. Plus, some of the choices were difficult.”

In fact, the choices were not difficult. It was the group pressure to give the wrong answer that made the choices seem difficult.

Although most subjects were not totally conformist like the one just described, the amount of conformity was, nevertheless, shocking. Without a group giving wrong answers, 95 percent of subjects performed

without a single error

. But with the group, only one-fourth of the subjects were able to maintain this perfect performance. Most subjects caved to group pressure about one-third of the time.

Asch’s debriefing procedure revealed that most subjects had some awareness of what they were doing, although as just illustrated, most subjects underestimated by a large degree the number of times they went along with the group. Some just accepted the group’s judgment as an indication that their own perceptions were wrong. One particularly conformist subject stated, “I just wondered what was wrong with me.”

Another said, “There were so many against me that I thought I must be wrong.”

Others gave no evidence that they were even aware of the fact that they were wrong.

See as I Say

Asch was an iconoclast himself, single-handedly creating the field of social psychology. As a Polish Jew conducting experiments in the years following WWII, Asch aimed to understand how millions of Germans could blithely follow the Nazi ideology of extermination. Asch’s approach, which stands as one of the most influential psychology experiments of the twentieth century and has been replicated hundreds of times, showed that even when you strip away all the ambiguity of what an individual sees, and there is no possibility of personal gain or reprisal, people will still go along with the group.

The social psychologists who followed Asch favored this explanation of conformity: we know what we see, and we know right from wrong, but with enough social pressure, we cave in to the fear of standing alone. Ironically, this explanation of conformity contains a certain heroic element that accounts for its persistence. If we grant that we are all a bit reticent at times to stand up for our personal opinions, this leaves the door open to act as individuals when we choose. It is a noble grasp for free will. But—and this is the kicker—we must be brave enough. This was Asch’s point. Even in a neutral laboratory setting, most people are not that brave.

Now you may think,

Surely, I would be brave enough to stand my ground

. True, not everyone in Asch’s experiment went along with the group. But even if some are not that brave, they might think that they could decide, for whatever reason, whether to go along or not. But what if that is wrong, and we do not have as much free will as we’d like to think? What if groups of people change how we see the world? Then we

are dealing with a much more pernicious form of conformity: a form of conformity we might not even be aware of and one that dooms the would-be iconoclast before he even knows it.

The extent to which perception can be altered by fear is a question that has lingered over social psychology. It is a difficult question to answer, for if a person’s perception were truly altered, he might not even know it. Asch realized that at least two distinct mental processes go into making a perceptual judgment like his line task. The first is perception itself. As we saw in the first chapter, perception is shaped not only by what the eyes transmit but by an individual’s expectation of what they are seeing. The second process—judgment—is a type of decision making. In Asch’s experiment, the decision was simple: picking the two lines that were the same length. It is important to note that these are distinct cognitive processes and are potentially mediated by different circuits in the brain.

Ever since Asch, most social psychologists have assumed that conformity is exerted at the decision-making stage in a sort of spineless capitulation to the majority. Nevertheless, hints of perceptual shifts can be found throughout the literature on social conformity. Even Asch reported several subjects who marched along with the group and yet seemed blithely unaware that they were wrong. Their unawareness suggested, but by no means proved, that their perception had been altered. The traditional entrée into a person’s perception is to ask him or her—either directly, or indirectly through experiments. But no matter the method, perception has never been fully separated from the judgment process. At least until fMRI came along.

Although neuroscientists have been using fMRI to systematically map out the neurobiology of processes such as memory, emotion, attention, and perception, nobody had thought to use fMRI to answer the looming question of whether other people can change what you see. To answer this question, in 2005 my research group tackled the problem of how fear might change perception in a modern variation of Asch’s experiment.

10

The logic of our experiment was simple. If other people change what you see (or what you think you see), then fMRI should detect changes in perceptual regions of the brain. If, on the other hand, conformity occurs at the decision-making level, we should see changes in decision-making regions. As we saw in the first chapter, visual information originating from the eyes first hits the brain in the back of the head in the occipital cortex. The information then flows forward, splitting into two paths—one through the high road in the parietal cortex, the other through the low road in the temporal lobe—and they meet again in the frontal lobes. Because perception occurs largely in the first stages of this process, in the back of the brain, we hoped that we could separate the perceptual side of conformity from the decision-making side.

No matter how it turned out, the answer would have wide-ranging implications for how we, as individuals, make decisions in groups. Take, for example, the democratic institutions that have been erected in the last two centuries. They all depend on self-determination. In the Bill of Rights, we protect the liberties of individuals. In return, there is an implicit contract that requires everyone to participate in the governance of society. This includes voting for representatives, adherence to the rule of law, trial by jury, and the conduct of business according to accepted practices. We allow for differences of opinions, but these differences are resolved through institutions such as voting. Beneath all these institutions lies the assumption that individuals “call it as they see it.”