If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (10 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

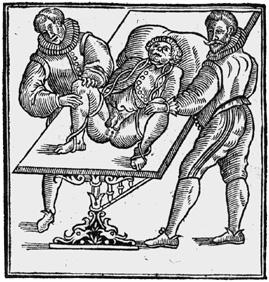

‘Cutting for the stone.’ Samuel Pepys underwent the operation to remove a stone from his bladder in his own home

Even while the medical profession was becoming established, the bedroom at home remained the scene of many a crisis. When Samuel Pepys, for example, had a stone in his bladder removed, his surgeon came to his house to perform the operation. The preparations took place in his own bedchamber. He was tied down on a table so that he could not thrash about, and two strong men were also present to ‘hold him by the knees’ and ‘by the arm-holes’.

With the Enlightenment, though, the bedchamber began to lose its role as an operating theatre. Those in need began to turn to the professionals. There were physicians who would still visit you at home for a fee, but also surgeons who could perform operations in their own shops, and apothecaries and chemists who could sell you herbal remedies and drugs from commercial premises. Early hospitals (places for the provision of hospitality)

were mainly places for the relief of the poor and indigent, rather than for curing the middle and upper classes. So on into the nineteenth century a professional nurse might still arrive to help a wealthy family with a sick member turn a bedroom into a sickroom. Eventually, though, by the twentieth century, illness became firmly associated with the surgery and hospital. Today, the very idea of a doctor making a ‘home visit’ sounds unusual and retrograde: it seems like a practice from a more leisurely past.

Medical drama in the bedroom is much rarer than it used to be. Now that 58 per cent of us take our last breath in a hospital, we’ve forgotten that once everyone expected to die at home.

7 – Sex

Would you rather sin with Elinor Glyn on a tiger skin?

Or would you prefer to err with her on some other kind of fur?

Verses on Lord Curzon’s lover, romantic

novelist Elinor Glyn, 1864–1943

We tend to assume, along with Philip Larkin, that ‘Sexual intercourse began/In nineteen sixty-three … Between the end of the

Chatterley

ban/ and the Beatles’ first LP.’ There was a curious reluctance to talk about sex for well over a century, between 1800 and 1960. Yet before that copulation was openly discussed, with much less stigma and shame.

Nor was sex restricted to the bedroom. Edmund Harrold, a priapic wig-maker living in late-Stuart Manchester, kept a detailed diary of his sex life, including comments such as ‘did wife 2 tymes couch & bed in an hour an[d] ½ time’. In 1763, James Boswell exceeded him with a clever actress/prostitute named Louisa: ‘a more voluptuous night I never enjoyed. Five times was I fairly lost in rapture … I was somewhat proud of my performance.’ On this occasion they were in a bed, but it’s only fair to point out that the lanes and fields were far more attractive to medieval and Tudor young people who lived in otherwise communal spaces. The fact that early bedrooms were shared could certainly inhibit romance. The seventeenth-century

Abigail Willey of Oyster River, New England, would stop her husband ‘coming to her’ when she didn’t feel like it by making her two children sleep in the middle of the bed rather than taking their usual position at the sides.

We don’t hear Harrold’s wife’s or Louisa’s side of the story, and there’s a widely held notion that the church has always encouraged the missionary position as it kept a woman in her rightly subordinate place. But Harrold would have sex with his wife both in the ‘old fashion’ (missionary position) and the ‘new fashion’ (her on top), the latter especially when she was pregnant. And in fact, pre-modern female sexuality was considered to be powerful, formidable and valuable.

Medieval women who considered their husbands to be unsatisfactory could always pray at the shrine of St Uncumber in Westminster Abbey to be rid of them. (‘If the man’s member is always found useless and as if dead, the couple are well able to be separated.’) Alison, Geoffrey Chaucer’s ‘Wife of Bath’ in

The Canterbury Tales

, devoured no less than five husbands in her attempt to satiate her sexual appetite, and male impotence is no modern bedroom problem. Sir Tristram in Sir Thomas Malory’s

King Arthur and his Knights

could not perform with his wife because of intrusive memories of his former lover, Isolde. As soon as Isolde popped into his mind, he became all ‘dismayed, and other cheer made he none’. And having spoken of Henry VIII’s impotence was one of the accusations made of Anne Boleyn at her trial in 1536.

Medieval women were considered to have a right to an orgasm. As the author of the thirteenth-century

Romance of the Rose

put it, ‘one should not abandon the other, nor should either cease his voyage until they reach port together’. One fourteenth-century Oxford doctor recommended that frustrated sisters should simply do it for themselves: a woman should get her midwife to lubricate her fingers with oil, insert them into the vagina and ‘move them vigorously about’.

Yet society also condoned a long-standing division of labour between a mistress (provider of pleasure) and a wife (mother of children), and only a minority made a successful transition from the former to the financial security of the latter. Anne Boleyn was a notable exception, and did so by making Henry VIII wait six years before consummating their relationship. She allowed him addictive tasters along the way. As he wrote to Anne when they were apart, Henry was often lost in daydreams about her: ‘wishing myself … in my sweetheart’s arms, whose pretty duckies I trust shortly to kiss’. Once Anne was married, though, she had to put up with the occasional infidelity, especially during her pregnancies, when she was curtly told by her husband to ‘shut her eyes and endure as her betters had done’.

To modern eyes, a striking emphasis was placed upon a woman’s sexual pleasure in medieval times. This was because in medical terms the medieval female body was thought of as simply a weaker version of the male, a kind of mirror image of it, with the sexual organs placed inside rather than outside. The female orgasm, therefore, was thought essential to conception, just as the male orgasm was. (At the same time, Tudor medicine books contained remedies for complaints affecting a man’s ‘womb’.) The idea that a female orgasm led to conception was put like this in the seventeenth century: if a man feels during intercourse ‘a kind of sucking or drawing at the end of his yard … a woman may have conceived’. This was why Samuel Pepys was careful not to allow his many and varied mistresses to enjoy themselves, even while he insisted on taking his own pleasure. For women, another dreadful drawback to this belief was what happened in cases of rape. If a raped woman became pregnant, she must have experienced an orgasm, therefore she was not raped.

However, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the female orgasm entered into decline, and people began to question its very existence. Physicians discovered, during the course of the Enlightenment, that orgasm is not in fact necessary for

conception. As a result, the importance society attached to sexual pleasure for women plummeted. Thus we get the stereotype of the frigid Victorian age, with females frightened of sex. Victorian women were not expected to experience orgasms; the official line was that their doctors and husbands thought them incapable of it.

This change in biological understanding had enormous implications for society. Women gradually shed their medieval stereotype as insatiable temptresses in order to become the Victorian ideal of pure, chaste, virginal angels. A society where sexual order was maintained by physical chastisement gradually began to give way to internal moral codes, where behaviour was policed by social forces such as shame and expulsion from the community for sexual transgression. Even before the end of the seventeenth century, the historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich notes, the New England county courts which had dished out whippings and convictions in the early settler period began to lose their grip, and fines began to replace beatings. The result: less violence, but more psychological repression. So the modern mentality was born. Only when, in the later twentieth century, sex began to be considered as something pleasurable for women in its own right – not merely as wives or mistresses – did the female orgasm return to prominence in scientific and public discourse.

Despite the earlier emphasis on female pleasure, a respectable married woman was monogamous. In the medieval and Tudor ages, the sexual urges of young men were cleverly sublimated through the cult of chivalric love: they were supposed to devote themselves to the service of ladies of superior social status, and to expect nothing physical in return. (Favours, patronage and promotion at court were all acceptable alternatives.)

The chivalric cult had a strange parallel in the sleeping arrangement known as ‘bundling’, which was common both to rural areas of seventeenth-century Wales and to eighteenth-century

New England. This was likewise a non-sexual relationship, where a young man and woman passed the night alone in a bedroom together, but remained fully clothed. Sometimes they were even tied down or a board was placed down the middle of their bed. The idea was to make it through to morning without having sex, in order to find out whether they got on well enough together to marry. Until 1800, when it began to arouse a new moralistic disapproval, to ‘bundle’ was considered both chaste and sensible as it led to more successful marriages:

Cate Nance and Sue proved just and true

Tho’ bundling did practise;

But Ruth beguil’d and proved with child,

Who bundling did despise.

The other explanation for this curious custom can be found in the architectural design of pre-modern rural cottages. Obviously, in an age when houses contained far fewer rooms than there were family members, the young people were short of private places in which to become acquainted. It was a kindness on the part of a girl’s parents to leave a young couple alone together in the upstairs bedchamber, the rest of the family gathering in the kitchen or parlour below instead. The ropes and the board assuaged the parents’ conscience, as they were responsible for finding their daughter a suitable husband, yet also for preserving her virginity. On the other hand, pre-marital sex was not seen as disastrous for people of the middling or lower sort, and a pre-marital pregnancy could be welcome proof of fertility. ‘You would not buy a horse without trying it first,’ explained one Norfolk farmer to his vicar.

The process of creating royal or aristocratic children, though, was the business of the whole nation, and its importance was so great that it took place in a semi-public context. The proxy bedding of Henry VIII’s sister, Mary, sounds rather undignified, yet the process saw her legally wed. Mary lay on a bed in what was described as a ‘magnificent

déshabille

’ with bare legs. The

French king’s ambassador took off his own red stockings and lay beside her. As their naked legs touched, ‘the King of England made great rejoicing’. (When Mary finally reached France, its elderly king was delighted with his new bride and boasted ‘that he had performed marvels’ on his wedding night.)

A century later, another English princess named Mary, aged only ten, had to endure a public bedding with her brand-new husband, the fourteen-year-old Prince of Orange. The bride’s father, King Charles I, ‘had some difficulty in conducting’ his new son-in-law through the thick throng of spectators gathered around the bed where the young princess lay waiting. Once in bed, the boy prince ‘kissed the Princess three times, and lay chastely beside her about three-quarters of an hour, in presence of all the great lords and ladies of England’. After this, his duty was considered done.