If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (12 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

Illegitimate babies were no strangers even in high society, but there their birth could be much more easily hushed up. In

the chapel of Georgian St James’s Palace, some babies mysteriously ‘dropped in the court’ were baptised; no one knew who their mothers were, but various Maids of Honour seemed suspiciously willing to stand as godmothers. By the early nineteenth century, poor Princess Sophia, daughter of George III, could not be found an appropriate Protestant prince as a husband because of a shortage in supply, and marriage to a commoner was out of the question. So, in desperation, she embarked upon an affair with one of the very few men she knew: an equerry of her father’s called Colonel Garth, thirty-two years older than herself and described by his colleagues as ‘a hideous old devil’. She gave up her child.

It’s very noticeable just how much bigger Victorian families were than Georgian ones: an average of six children as opposed to 2.5. Part of the reason was a decline in the age of marriage. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, most non-aristocratic women got married in their mid-twenties (having saved up a nest egg through work). They were therefore well advanced into their fertile years even before they began to procreate. (Once they’d started, though, they did not readily stop, but frequent infant deaths brought the average number of children down.) In an industrial economy, though, so much more wealth was generated that a man could go out to work and win the wages to support a wife at home. Victorian marriages therefore took place at a younger age, and more babies survived.

For those who didn’t want babies, condoms were available from the late seventeenth century onwards, and there was always the method of coitus interruptus (rather quaintly described as ‘to make a coffee-house of a woman’s privities, to go in and out and spend nothing’.) Reliable contraception in the twentieth century, as we know, has had an enormous effect on society, and to read certain newspapers infertility or ‘leaving it too late’ seems almost as big and regrettable a social issue as unwanted pregnancy.

9 – Deviant Sex and Masturbation

I used to masturbate whenever I thought about Lady Jane Grey, so of course I thought about her continually.

Nancy Mitford, 1948

A piece of pornographic graffiti pencilled onto a staircase wall by a bored page at Hampton Court Palace in 1700 shows a lady with legs akimbo, naked except for a pair of very beautifully drawn shoes. Given the sketchy nature of the rest of the depiction, and the care lavished on the footwear, it seems safe to conclude that he must have been a foot fetishist.

The main point to make in a history of sexual deviancy is that sexual preferences and orientations formed very little of a person’s social identity until the late twentieth century. So there were no labels of ‘homosexual’ or ‘lesbian’ (or even ‘child molester’ or ‘voyeur’), just people who, from time to time, performed such aberrant actions. The Earl of Castlereagh, executed at the Tower of London in the early seventeenth century for sodomising his footman, was tried and condemned by his peers. What really upset them was not the sodomy but the fact that he’d slept with one of his servants.

The beginnings of a homosexual subculture do appear in the early eighteenth century in the ‘molly-houses’ caricatured by the London writer Ned Ward. From these origins grew a whole

group of people who would eventually publicly describe themselves by their sexuality.

Strikingly, lesbian actions are described in medical textbooks long before any hint is given that males might have sex with each other. Perhaps it was a matter of salacious interest for their male authors. Certainly the seedy seventeenth-century uncle of one Nicholas LeStrange would say ‘whensover he saw two women kiss, (otherwise then in the way of salutation) Oh how my breech waters at that’. Queen Anne suffered from negative rumours that she had ‘no inclination for any but of one’s own sex’. But behind the accusations lay fears that women were too powerful at her court, and that they were disrupting the flow of political advice that should stream to the queen from her male courtiers. The practice of sharing beds meant that homosexual actions were surely an accepted part of life for many of both sexes, and they only caused problems when they emerged from behind the bedroom door.

The most interesting period in the history of masturbation was the nineteenth century, when the anti-masturbatory propaganda and scare-mongering information issued to young people had much in common with the anti-drug campaigning material of today. Why did this great wave of fear grip society and cause so much guilt in the bedroom?

Excessive lust seems to have been a problem as old as humanity. Hildegard of Bingen in the twelfth century recommended wild lettuce as a medicine which ‘extinguishes lust in a human. A man who has an overabundance in his loins should cook wild lettuce in water and pour that water over himself in a sauna bath. He should also place the warm, cooked lettuce round his loins.’ But the first book devoted to the dangers of masturbation –

Onania, or the heinous sin of self-pollution, and all its frightful consequences in both sexes considered

– appeared in Georgian London in 1715, where urban life was booming. One explanation for the anti-masturbation movement may lie in the

fact that cities distanced people from nature. They created a growing concern with appearances and correct behaviour, and people moved from being producers to consumers. Then there was the influence of the new ‘rational’ trend in thought and habits. If you prided yourself upon your enlightened rationality, you might well have considered that sexual pleasure without reproduction was pointless and therefore wasteful and wrong. The writer of

The Ladies Dispensatory

(1739) thought female masturbation simply dreadful: women who’d learned to become ‘capable of pleasuring themselves’, he said, were foolishly and wrongly turning down good offers of marriage.

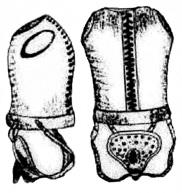

By the nineteenth century, young men were routinely warned of the ‘dangers’ of masturbating, and there were even devices available to make sure it didn’t happen. While it’s quite upsetting to imagine generations of youngsters genuinely believing that they might go blind through pleasuring themselves, the nineteenth-century solutions for preventing them from doing so were often amusingly and crazily Heath Robinson-like in character. The ‘Leather Jacket Corset’ (invented in 1831) included a metal penis tube and ‘prevented access to the testicles’, while ‘The Timely Warning’ was a penis-cooling device that employed cold water to cool ‘the organ of generation, so that the erection subsides and no discharge occurs’.

Now, most people think that as long as the bedroom door is closed, anything goes, and masturbation is a topic for humour not shame.

‘Dr Fleck’s leather corset’, one of many inventive Victorian anti-masturbation devices

10 – Venereal Disease

Oh! Now I have a pressing need to make water … Oh! It scalds me to Pieces … ’tis like Fire … – I have heard and read of pissing Pins and Needles, But never felt what it was till now.

So wrote a sufferer from venereal disease in a striking blow-by-blow account of his symptoms on 9 September 1710. He was experiencing its classic symptoms: pain in urinating and purulent matter dripping from the urethra. ‘These damned twinges, that scalding heat, and that deep-tinged loathsome matter are the strongest proofs of an infection,’ ranted fellow victim James Boswell in 1763. He believed himself to be afflicted by ‘Signor Gonorrhoea’, but at this point people still couldn’t distinguish between gonorrhoea and syphilis. The latter was the more serious: years after the first infection, the symptoms could reappear and culminate in flesh decay, paralysis, madness and a horrible death. Whichever of the two he had, Boswell was understandably gloomy at being confined to his bedroom for several weeks of treatment.

In common with their predecessors and successors in practically all other periods, commentators writing during the First World War thought that the morals of young people were in rapid and dangerous decline. ‘Social customs and traditions are altering rapidly in a most undesirable direction,’ thundered the

author of

The Changing Moral Standard

, as ‘girls, unmarried women and young married women of all classes’ had started behaving like prostitutes. In the early twentieth century, the arguments of campaigners against gonorrhoea shaded into eugenics. One pamphlet issued by the National Council for Combating Venereal Diseases claimed that couples who wanted to marry should obtain approval from a priest and a lawyer, but also from a doctor: ‘surely there can be no sanctity in any marriage unless blood-cleanness and freedom from infectivity are regarded as essentials?’ A printed warning issued to soldiers proposed a more practical solution to the problem of venereal disease: a visit to ‘special treatment centres … where examination is SECRET, FREE OF CHARGE, and CARRIED OUT BY EXPERT DOCTORS’. (People could find the location of their nearest centre by asking a policeman.)

An old procuress, with patches covering up her pox, takes an innocent country girl under her wing

Syphilis first reached Europe from the New World late in the fifteenth century, and then spread rampantly through sexual contact. It could not be transmitted through the air, even though the over-powerful Cardinal Wolsey was accused of having ‘breathed’ syphilis over Henry VIII. While the humour-based concept of medicine still reigned, the recommended treatment was with mercury. (‘Five minutes with Venus may mean a lifetime with Mercury.’) The intention was to make the body sweat excessively, which would restore equilibrium. Syringes for injecting mercury into the urethra sank with the

Mary Rose

in 1545, to be rescued by modern divers. Otherwise a mercury ointment could be rubbed onto the skin, and there were even bizarre anti-venereal underpants coated with the chemical. The mercury did indeed cause a patient to sweat, but the resultant black saliva thought to indicate that the treatment was working was in fact a symptom of advanced mercury poisoning.