If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (23 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

In the later eighteenth century, the design of the flushing toilet underwent several improvements which helped to make it more popular. Alexander Cumming in 1775 made the vital step of inventing the S-bend, the kinked waste pipe which stopped smells from coming back into the room. Previously water closets had featured the D-bend drain, but this design trapped stinking water in the system.

In 1778, Joseph Bramah patented his own particular model of water closet which featured a fifteen-second flush timed by a brass air cylinder. (Bramah also invented the hydraulic press and a famously complicated lock: some northerners still refer to a particularly knotty problem as ‘a Bramah’.) He was born on a farm in Yorkshire in 1748, but an early accident put an end to his labouring life and he became apprenticed to a cabinet-maker instead. He was installing a water closet for a client when he realised that he could create a better one himself. His excellent design would lead the field for the next century.

Bramah’s showmanship and his eagerness to promote and install his water closets made his a well-known name. He claimed

to have fitted 6,000 closets across the country by 1797. Queen Victoria would order one of his models for Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, where it still remains in working order. But even Bramah’s water closets were not perfect. They had a hinged valve at the bottom of the pan, and inevitably this leaked a little.

Indeed, there were problems with all the various Georgian water-closet systems. They needed priming with water daily, and did not always flush successfully. The valves could malfunction, wood could splinter, and their iron pots retained smells and ‘ancient ordure’. Another difficulty with water closets was their position off corridors. As the eighteenth century wore on, sensibilities grew more refined. There was no more public pissing; people, especially ladies, did not want to be seen or heard leaving their bedrooms at night to use the facilities. So chamber pots continued to be used. Simple, tried-and-tested earth closets (just a wooden seat positioned over a midden) in the backyard also remained popular in rural areas.

Another problem which delayed the widespread adoption of the flushing toilet was its requirement for a proper sewerage system. For most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, people’s faeces were collected in cesspits behind or beneath their houses. They were periodically emptied by ‘night-soil men’, who in London took excrement to use as manure on market gardens to the north of the city. By 1800, the city’s million residents had 200,000 cesspits between them. But from each of them polluted water would leak through the soil into London’s rivers.

Cesspits completely failed to cope with the arrival of the flushing toilet, which produced waste now mixed with a large amount of water. In 1815, it was made permissible for individual houses to link their drains into the London sewers intended to carry rainwater from the streets down to the river. By 1848, this became mandatory. There was no longer any need for cesspits and night-soil men, but the result was that raw sewage was being piped straight into the Thames. In 1827, a pamphleteer

described the river as ‘saturated with the impurities of fifty thousand homes … offensive to the sight, disgusting to the imagination, and destructive to the health’. This was the very river that still supplied many people with their drinking water.

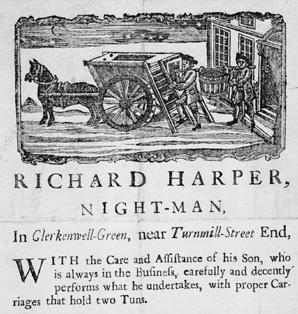

The trade card of Richard Harper, one of the ‘nightmen’ who carted away London’s nightsoil

Obviously, such a primitive means of sewage disposal presented a major public health hazard. London suffered from four major outbreaks of cholera during the nineteenth century, in 1831–2, 1848–9, 1853–4 and 1866. But the link between cholera and an infected supply of drinking water was not made for a considerable length of time. The scale of the problem was underestimated because of contemporary misunderstandings about the nature of disease.

Rather than realising that cholera was water-borne, people

still persisted in believing that a ‘miasma’ of disease moving unstoppably through the air made you ill. The idea that houses should be better ventilated took priority over drainage. Even Florence Nightingale, in her

Notes on Nursing

(1869), condemned the idea of connecting houses to drains, because she thought odours rising from the drains would bring with them scarlet fever and measles. She was not alone in her suspicions: when Linley Sambourne installed a plumbed-in wash basin in his wife’s bedroom at Stafford Terrace, Kensington, she kept the plug in the basin at all times as a guard against evil vapours.

It took a long battle by the heroic Dr John Snow to get anyone to appreciate what he had understood from 1854 onwards: that cholera was spread through water, and that better drains and sewers would help, not hinder, health. Snow’s surgery was in Broadwick Street, Soho, and he noticed that many local cholera victims had been using a pump fed by a well in his street. This well was in close proximity to a sewer. Certain that water from the well was causing deaths, Dr Snow persuaded the parish council to remove the handle from the pump so that people couldn’t use it. Deaths consequently fell. But he had great difficulty in persuading his colleagues of his findings, because the water that actually contained the cholera bacilli looked perfectly clean and wholesome.

Yet everybody became persuaded of the need to invest in a proper sewerage system by the Great Stink of July 1858. A particularly hot spell of weather caused the Thames to give off a terrifically dreadful smell. It even penetrated the Palace of Westminster, giving the country’s legislators a graphic and timely reminder that London lacked proper sewers. They had to hang sheets soaked in lime across their windows as a barrier to the stench.

In fact, improvements were already in hand. London’s Metropolitan Board of Works had been established in 1856, with Joseph Bazalgette as its chief engineer. Bazalgette was in the process

of creating a network of sewers beneath London which would not take waste directly to the Thames but eastwards instead, so that sewage would enter the river downstream of the city and its water supplies. It was noticeable, in the fourth cholera bout of 1866, that only the East End was affected – the sole area yet to be connected to the not-quite-yet-complete sewerage system.

Bazalgette’s work was one of the true marvels of the Victorian age. He would eventually use 318 million bricks to construct over a thousand miles of sewer, and his works to drains, embankments and bridges cost more than twice as much as Brunel’s Great Western Railway. Most remain in use today, underground cathedrals of brick and water.

Bazalgette’s sewer revolution would allow the water closet to become standard in most homes. The Great Exhibition of 1851 had also helped to popularise the flush, through the public toilets provided for its visitors. (Those for ladies were a late addition to the project: initially only men’s needs were considered.) Some 14 per cent of the six million visitors to the exhibition used the facilities, many of them experiencing the flush for the first time. This was despite the fact that they cost a penny to use – hence the expression ‘spending a penny’.

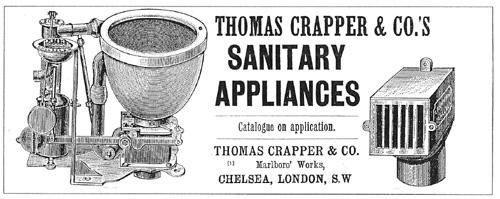

So flushing toilets entered many homes, and now Thomas Crapper became a household name. The famous motto for his toilets, produced from 1861, was ‘a certain flush with every pull’. His is the best-known name in the history of sanitary innovation, but this was really because he became a figurehead for the new industry of sanitaryware rather than because of any particular technological breakthrough he made. His genius was in sales and promotion. He was a self-made man who walked from his native Doncaster to London, at the age of eleven, to find employment with a plumber in Chelsea. Perhaps the apogee of his career was his royal warrant, won after installing toilets at Sandringham House for the Prince of Wales, and his company survived until 1966.

An advertisement for Thomas Crapper’s products … but, contrary to popular opinion, he did not invent the flushing toilet

Despite the suggestions made in his company’s advertising, none of his nine plumbing patents were actually for the marvellous flushing siphon cistern. The credit for inventing this new and thunderous flush, produced by a pivoted arm balanced by a counterweight, must go to Joseph Adamson of Leeds, who took out his patent in 1853. Crapper did not even manufacture his own toilets: the products which bore his name were made by various other firms, mainly in Staffordshire, and he merely sold them on. (It was not unusual for one firm to stamp another’s name on its bathroom wares.) Stoke-on-Trent, with its good local supplies of coal for firing the kilns, was becoming the toilet capital of the world.

Contrary to popular opinion, the

Oxford English Dictionary

notes that the verb ‘to crap’ was in use long before Crapper’s company became widely known. ‘Crap’ was an old English word for rubbish, taken by the Pilgrim Fathers to America and used over there as a slang expression for ‘faeces’. When American soldiers came over to Britain in 1917 to help fight the First World War, they were highly amused to encounter toilets with cisterns marked ‘CRAPPER’. But this was just a coincidence.

Unfortunately not every toilet was a Crapper cracker. The obsolete D-bend remained in use in many places, despite the condemnation of professionals. At the Sanitary Exhibition in

Croydon in 1879, an engineer called William Eassie still felt it necessary to insist that he ‘should above all like to see abolished the filthy D trap with its furrings of faecal matter’.

The best form of toilet pan would eventually turn out to be nothing like the complicated valve-based system installed in the houses of rich early adopters. An alternative, robust and cheap model had begun to emerge in the 1840s, consisting of a crude ceramic bowl placed over an S-bend pipe. All across the country, the ‘Bristol Closet’, the ‘Liverpool Cottage Basin’ and the ‘Reading Pan’ were developed by local manufacturers. These simple devices were the direct forerunners of the modern toilet bowl sold today.

What about the terminology? The word ‘lavatory’ really means a place for washing, i.e. a washbasin, and its use to signify a water closet is a polite euphemism. There’s an argument that the word ‘toilet’, another euphemism, owes its existence to the railways. One’s

toilette

was originally nothing to do with defecation; it meant washing and dressing. Early train carriages had two separate rooms involving water: the ‘toilet’, for washing, and the ‘WC’ or water closet. When, in the early twentieth century, the washbasin and lavatory joined together into just one little room, the more discreet ‘toilet’ was the only word that remained on the single door.

Here’s George Jennings, the Victorian toilet impresario, using yet another, rather charming euphemism for the loo:

although my proposition may be startling I am convinced the day will come when Halting Stations replete with every convenience will be constructed in all localities.

He was writing with considerable prescience. Once the social and technical glitches had been ironed out, nothing could stop the triumphant progress of the flushing toilet. Two hundred and fifty years after its invention, it became an integral part of the British home.