If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (44 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

The timeless British vice of binge-drinking. The women have withdrawn to the drawing room to tea, leaving the men to overindulge in the dining room

The convivial gang of all-male drinkers could save time by having their chamber pots close to hand: hence their often being located – bizarrely to modern eyes – in the convenient cupboards of sideboards. But not everyone liked this lazy habit. According to the seventeenth-century Randle Holme, ‘the Jolly crew when met together over a cup of Ale’ should keep the chamber pot near by ‘not for modesty’s sake, but that they may see their own beastliness’. The visiting Frenchman de La Rochefoucauld was similarly unimpressed in 1784 by drinkers sharing a chamber pot: ‘The sideboard is furnished with a number of chamber pots and it is a common practice to relieve oneself while the rest are drinking; one has no kind of concealment and the practice strikes me as most indecent.’ Just as the English have always

thought the French effeminate, our neighbours have always thought us boorish in return.

Yet the English remained deeply attached to their ale. The eighteenth-century craze for gin caused consternation not only because of its powerful intoxicating effect, but also because it lacked the ancient, chivalric associations of beer, the drink that ‘gave vigour to the arms of our ancestors … made them wise in council, and victorious in the field’.

Even the vigorous, religiously inspired teetotal movement of the nineteenth century failed to stamp out the demon drink: 1877 was the year in which more alcohol per head was drunk than before or since. In 1915, the lamp-boy at Longleat House in Wiltshire remembers that still ‘beer was allowed regularly … it was served in copper jacks, sort of large jugs, and was even drunk at breakfast time’.

In the very same year, the chancellor David Lloyd George, a well-known supporter of the Temperance movement, claimed that alcohol was causing ‘more damage in the war than all the submarines put together’. But in fact the two world wars would severely reduce alcohol consumption much more than any government attempts to dictate on the matter.

The production of alcohol had by then moved firmly outside the home, and the brewing industry was severely disrupted in both 1914–18 and 1939–45 by the need to divert resources elsewhere. The amount consumed would remain much lower than the Victorian standard until the end of the 1950s. Then, the return of affluence saw alcohol resume a central position in home life. The cocktail party, the central image of 1950s hospitality, involved plying people with alcohol in one’s living room, and Mike Leigh’s play

Abigail’s Party

(1977) showed the same social occasion remodelled for the 1970s, with the house-proud but crass Beverley forcing her guests to drink themselves sick. Meanwhile, off-stage, the fifteen-year-old Abigail holds a raucous party of her own. The focus of the drinks industry during

the 1980s and 1990s would be upon young people, who might otherwise have turned to the readily available drugs instead for their intoxicants.

Drinking at home remains the bugbear of the nation’s landlords, and middle-aged, middle-class professionals casually having wine with their dinner every night are the group in society that consumes the most alcohol. A new awareness of the health problems it brings may have lowered consumption levels from their Victorian high. What still exists, though, in all its messy glory, is the ageless and very British concept of the binge.

45 – The Wretched Washing-Up

I hate discussions of feminism that end up with who does the dishes …

But at the end, there are always the damned dishes.

Marilyn French, 1978

Before the dishwasher, any grand house – and indeed many modest dwellings too – had a special room for washing up. The scullery takes its name from the Norman-French

escuelerie

, meaning dish room. The 1677

Directions for Scullery Maids

lists their duties as follows: ‘you must wash and scour all the plates and dishes that are used in the kitchen … also all kettles, pots, pans, chamberpots’.

The scullery wasn’t just for washing dishes, but also for rinsing food, and even for plucking or removing the entrails of fowl or flesh on their way into the kitchen. Big stone sinks were complemented by wooden kitchen units (you can see some surviving medieval ones at Haddon Hall in Derbyshire), and salting or preserving might also take place here.

In medieval sculleries, people washed the dishes with a nasty black soap made out of sand, ashes and linseed oil. At least it shifted grease. Their seventeenth-century descendants used a ‘soap jelly’, made by mixing grated soap with water and soda. The cunning scullery maid knew that copper pans could

be brightened with lemon and salt (I’ve tried this and it really works). Mrs Black, in her book

Household Cookery

(1882), was still recommending ‘warm water in which is a little soda. Once a week the sauce-pans ought to be well scoured inside. Rub the inside of tinned sauce-pans well over with soap and a little fine sand or bath-brick till they become quite bright.’

Washing up was always one of the very worst jobs in the kitchen. Albert Thomas, who’d done it many times himself, recalled that even a modest dinner party for ten in a wealthy household of the 1920s required no less than 324 items of silver, china and glass to be washed, in addition to the saucepans. Monica Dickens described the depressing state of her 1930s kitchen after dinner, when ‘every saucepan in the place was dirty; the sink was piled high with them. On the floor lay the plates and dishes that couldn’t be squeezed on to the table or dresser.’ She sobbed over many a late-night encounter with the Vim tin.

But many hands could make light work of the task. Indeed, in remote country houses, where entertainment was in short supply, washing up was even a mild form of fun: Eric Horne, the butler, recalled ‘a goodly company of us in the servant’s hall at night, as the grooms and under gardeners would come in and wash up … more for company than anything else’.

Washing dishes and cleaning plates is hard on the hands, and an off-duty footman could still be identified by the state of his thumbs. Unless a household employed a specialist plate-maid, it was he who would blister his digits rubbing jeweller’s rouge into silver. ‘Cleaning plate is hell,’ wrote Ernest King, another butler. ‘The hardest job in the house … the blisters burst and you kept on despite the pain and you developed a pair of plate hands that never blistered again.’ Cleaning knives was a similarly dark art. According to

The Footman’s Directory

, it was best done with a mixture of hot melted mutton suet and powder rubbed from a brick.

Like all other domestic duties, washing up could be used to express social hierarchy. In Princess Marina’s twentieth-century household at Kensington Palace, the princess herself washed her decorative and ornamental china collection twice a year. The butler washed the best china after family meals, and the ‘odd man’ did the ordinary china after the other servants had used it.

Only when the people who’d formerly employed servants began to have to do their own washing up did they realise how bad their kitchens had been for their servants’ backs. Lesley Lewis, recalling a country-house childhood in pre-war Essex, described the ‘two wide shallow sinks under the window … it was not until I washed up here myself, in the 1939 war, that I realised how inconvenient the equipment was’. The explanation for many inconveniently low sinks is rather depressing: often they were intended for use by the young, and children were the dishwashing machines of choice in many kitchens.

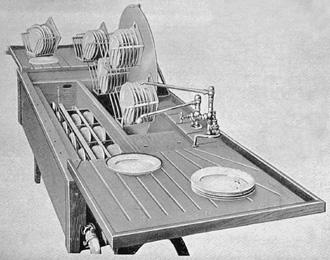

An early mechanical crockery washer from

c

.1930

The first patent for a mechanical dishwasher was taken out in the US by one Joel Houghton in 1850. He designed a wooden tub with a handle at one side: you turned this to spray water

somewhat ineffectually onto the dishes. Like so many other contraptions, it was only really made practical in the 1920s when both piped water and electrical power could be readily employed. The dishwasher, though, belongs with the extractor fan and the electric mixer, rather than the cooker or the refrigerator: it did not become a widespread commercial success until well after the Second World War.

Conclusion: What We Can Learn from the Past

The palsy increases on my hand so that I am forced to leave off my diary – my phrase now is farewell for ever.

Last written words of Lady Sarah Cowper, 1716

This is the end of one story, but the beginning of another.

Today’s homes are warmer, more comfortable and easier to clean than ever before. But I believe that the next step in their evolutionary journey will be a strangely backward-seeming one, and that we still have much to learn from our ancestors’ houses. In a world where oil supplies are running out, the future of the home will be guided by lessons from the low-technology, pre-industrial past.

In Britain today, the current ‘Lifetime Homes’ legislation governing the design of new houses is curiously medieval in tone. It insists that, once again, rooms should be able to multitask. The living room must have space for a double bed in case its owner becomes incapacitated and can’t climb upstairs to bed. There must be room downstairs to install a lift to reach the bathroom if necessary. The age of specialised rooms, which reached its height in the nineteenth century, is long since over, and adaptability is returning to prominence.

When the oil runs out, we’ll see a return of the chimney (

plate 41

).

The only truly sustainable sources of energy are the wind (hard to harness in urban areas), the sun and wood. Forests, if carefully cherished, could provide us with fuel for ever. ‘Biomass’, or wood-burning, stoves are already making a welcome return, and will grow increasingly popular as sources of domestic heat. The sun is also becoming more important in house design. Once upon a time, people selected sites with good ‘air’; now, well-thought-out houses are situated to minimise solar gain in summer, and to maximise it in winter. Most houses will need to face south, to accommodate heat-buffering conservatories and solar panels on sloping roofs, a change that will destroy our now-conventional street arrangements.

The return of the chimney serves another purpose as well, and examples can now be found even in modern buildings without fireplaces. It allows natural ventilation. It lifts stale air out of the house, just like the funnel does on a ship. Mechanical air conditioning uses valuable energy and will soon become simply unaffordable, but a simple chimney containing a heat-recovery unit allows fresh air in while retaining the heat from stale air going out.

Upon the medieval model, walls are getting thicker, for insulation – to keep warmth in – and, increasingly importantly, to keep heat out in a warming world. Windows will grow smaller once again, and houses will contain much less glass: not only because of the intrinsically high energy cost of the glass itself, but because it’s such a thermally inefficient material. I myself live in a tall glass tower, built in 1998, and must agree with Francis Bacon, who condemned the great glass-filled palaces of the Jacobean age. In a house ‘full of Glass’, he wrote, ‘one cannot tell where to become to be out of the Sun or Cold’.