IGMS Issue 4 (6 page)

Authors: IGMS

I rose, turned my back on them and stalked through the airlock into the LM.

Commander Gutierrez caught up with me just outside my quarters. "That's it? That's all you're going to say?"

I stopped. "Yes."

She looked at me appraisingly. "You know they'll all hate you for that little show and not-tell."

I shrugged. "As long as they're united again. . . That's what you wanted, right?"

Gutierrez nodded. "Just between you and me, though, who was it in the picture?"

Cocking an eyebrow, I said, "Assuming it was one of the great religious leaders of the past, how on Earth -- or Aurora -- would I know him from Adam?" I hit the button to open the hatch to my quarters. "Now, if you'll excuse me, Commander, I have a column to file."

The mystery of just who Alla Beeth was and how he got to Aurora may never be fully explained. But as Earth's first ambassador to Aurora, he prepared the way for peaceful relations between our two worlds. And for that, we can only say, "Thank you, thank you very much."

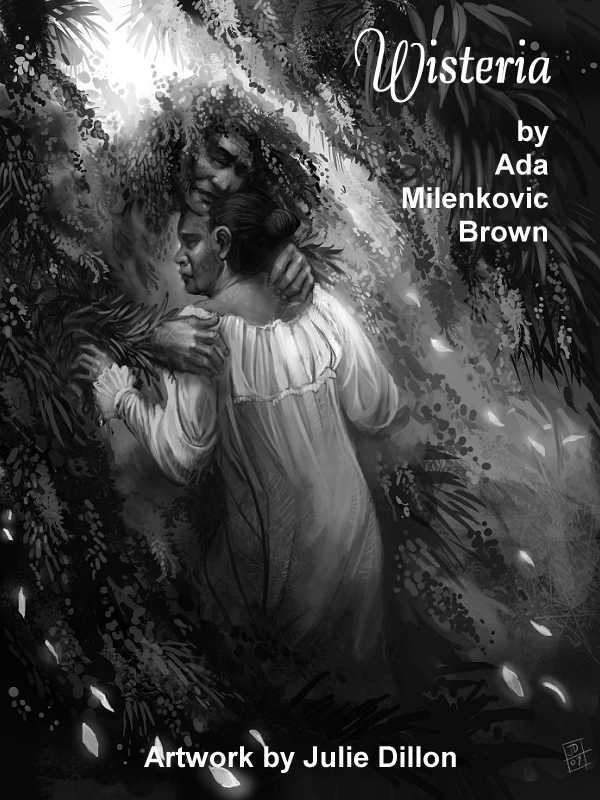

by Ada Milenkovic Brown

Artwork by Julie Dillon

When Dahlia got out of Junior's truck in front of the three story house, the first thing she noticed was the face in the leaves. The stone carving jutted out from the center of a rock terrace, a carving of a man's face with a leaf beard, his eyes peeking out from more leaves all round them, as if the leaves had wound together as they grew and that had somehow made a man. For just a minute, she tried to make it out that it was Garner's face. But of course it wasn't.

A mess of flowers, mostly red and yellow, surrounded the terrace along with a rock garden, with here and there a weed in amongst the rocks. Garner could have told her the names of the flowers. But Garner had been gone five years now.

Junior waved and drove off, his riding mower rattling a little on top of the flatbed. Dahlia straightened her tote bag and looked again at the garden with the face watching her cross up toward the house. If Garner or even Junior had care of it, they'd have made sure the yard was better weeded.

A lady with wispy silver hair and a bright yellow sun dress stood nervously beside the front door. She cleared her throat, so Dahlia looked at her.

"Are you Mrs. Meeks?" the lady said to Dahlia. She talked like she came from up north.

"Most folks call me Dahlia." Which was true about white folks anyway, at least the older ones. The younger ones had been calling her Miz Dahlia, just like everyone else, ever since Civil Rights had made its way east of Wilson. But she felt it wasn't her place to tell anyone to call her Miz.

"The kitchen's this way." The lady smiled like she was having her picture made. It often seemed to make Northern ladies a little nervous to have hired Dahlia to cook. But they didn't really have no choice about that. Dahlia was the best cook in the county.

The lady said, "I did tell you, didn't I, my tea is at one p.m. tomorrow?"

"That's fine. I'll be baking the cakes today, and then tomorrow morning I'll come back to fix the sandwiches and the shrimp." Dahlia followed the lady through the living room, winding past two over-stuffed sofas decorated with vines and big flowers. The pattern was echoed in a border that ran just below the ceiling. It was funny about the white folks Dahlia worked for, how a lot of their houses looked alike. The rooms were too big and the furniture too far apart -- like they never wanted to sit close and be friendly. No way to even sit outside at all except fenced in by a swimming pool. Swimming pools didn't set with Dahlia. Drown you if you weren't careful.

Their shoes tapped along the oak floors into the kitchen. Dahlia opened her tote bag and pulled out a faded calico apron and put it on.

The lady -- Miz Torrance, Dahlia recollected finally -- pointed out canisters of flour, sugar, and cocoa. Then the pans and the bowls on shelves. "I think I've got everything you mentioned on the phone."

Dahlia nodded. "I'll get to work then. Oh, and Miz Torrance? Tomorrow my son's landscaping over by Chocowinity. So I'll need you to come pick me up. As I don't drive."

Miz Torrance blushed a little. "Of course. Could you write down directions?"

Dahlia handed her a piece of paper where Junior had done just that.

"The second stoplight -- is that what this says?" Miz Torrance stuck the paper out to Dahlia.

Dahlia told her she didn't have her reading glasses, but yes, if she was talking about downtown Grimesland, you turned at the second stoplight, which was Beauford Street. Dahlia edged toward the refrigerator and hoped Miz Torrence had no more questions about Junior's note, or at least not enough questions to figure out that Dahlia couldn't read good. But Miz Torrance just smiled weakly and backed away. So Dahlia paid her no more mind, but washed her hands and set the butter out to soften.

When she got to running the mixer, two pairs of feet pattered in behind her.

"What are you making?" This was a tow-headed boy about five.

Dahlia ticked it off on her fingers. "Caramel cake, coconut cake, and dirt cake." The last was for the children.

"Dirt cake! Yuck!"

On Dahlia's right was the girl, who was taller, but looked just like the boy except with dark braids. She clicked her tongue at her brother. "It's chocolate."

"That's right. See? Gonna crush these cookies for dirt." Dahlia held up a package of oreos. "And put in candy worms."

"Gummi worms," the girl corrected her.

"Cool." The brother ran to another room where soon a TV was coughing out explosions and foolish music.

The sister got on tiptoe and set her head on folded arms on the counter beside the cake bowl. "Sometimes I think he's developmentally delayed." She pronounced it very carefully.

Dirt cake brought Dahlia back to thinking about Garner. Dirt was his element. When they had married and moved into his Great Aunt Euphemia's shotgun house in Grimesland, there'd been nothing around it but dead grass and dirt. Garner had dug and planted and weeded. And little by little, year after year, it all turned green.

Till his heart attacked him.

Now, all that was left of Garner was leaves -- sycamores, hydrangeas, weeping willows, and wisteria. It was all Garner. It had his stamp. She'd just never thought to look for his face in it.

She pulled the coconut layers out with silvery mitts, ignoring the heat breath of the oven, and put in the big flower pot of dirt cake batter.

Time to get started on the frostings. Caramel first, that was the tricky one, you had to stir it just right when you heated it up or it come out grainy.

Yes, if you could see anyone's face in the leaves, it would surely be Garner's.

That night Dahlia tossed and turned in bed -- on her right side, on her back, on her stomach. It had been no use trying to sleep on her left side since Garner died. Because that was the side of the bed he slept on. Because even without turning that way, she could feel he wasn't there.

She wished she hadn't seen that carving. Now she wanted to see Garner's face in the leaves. Dahlia threw off the covers and put on her shoes. She slipped out the back screen door, which creaked as it closed, and she stepped into the grass.

The yard was warm and humid and bathed in moonlight. The sycamores raised dark branches like fingers into the air; the willows hulked over in mounds over their trunks. She studied the trees as she wound her way through. No face.

She circled past the hydrangeas, their blue flowers white in the evening, to the middle of the yard where the wisteria grew on a circle of trellises covered over with spokes of planking. It had been Garner's present to her on their thirty-fifth anniversary, and now the vines and grape clusters of flowers tangled down in their gazebo shape. She went all around it looking in through the leafy vines and cones of flowers. Then she went in the middle under the spokes to sit finally on the stone bench Garner had put there and stare at his gravestone.

Maybe the children had the right of it. Maybe it was foolishness to have him here instead of at the cemetery down by the church. Junior thought so sure, though he never said, but you could tell by the set of his back as he trimmed around the gravestone with his edge trimmer. Her daughter Larissa never stopped talking about it the minute she set foot in Dahlia's house. Mama, you shoulda' this and Mama, you shoulda' that. There was plenty of shoulda's Dahlia could say about Larissa's business -- Dahlia's grandbabies playing on that computer till all hours, getting no sleep -- but Dahlia kept

out

of other folks' business, and they should keep out of hers. Plenty of folk had family cemeteries on their land -- you could see graves every which way on the country highways. And besides, Dahlia would have felt in the church yard like she was leaving Garner. I'm here, she whispered. I won't go away this time. She stared around in the semi-darkness. Should have done this in the daytime. I'm here to touch your face. I'm here to hold your hand. No one answered her in the dark.

Tuesday was a busy day. She got to the Torrance house late, on account of Miz Torrance getting lost picking her up. She made ham biscuits in a whirlwind all morning, which near to wore out her fingers, kneading, patting, and cutting the biscuits to bake. Then the tea party, putting out cold shrimp, which luckily she didn't have to peel because Miz Torrance chose not to pay the extra fee, pimento cheese sandwiches, iced sweet tea, and hot coffee. And of course she put out the cakes. When the doorbell started ringing, she went back to the kitchen and did her homework, writing down the names of foods that she found on cans in the pantry. Occasionally she went in amid the chorus of chattering voices to restock the sandwich trays.