Imperfect Justice: Prosecuting Casey Anthony (19 page)

Read Imperfect Justice: Prosecuting Casey Anthony Online

Authors: Jeff Ashton

Tags: #True Crime, #General, #Murder

A shot of the overgrowth on the blanket by the time it was found.

Courtesy of the Orange County Sheriff’s Office

Once the crime scene unit moved onto the scene, they were remarkably careful with every aspect of the site.

Courtesy of the Orange County Sheriff’s Office

They painstakingly documented everything to make sure that no aspect of their work was subject to question.

Courtesy of the Orange County Sheriff’s Office

One of the crime scene workers laboring over the site.

Courtesy of the Orange County Sheriff’s Office

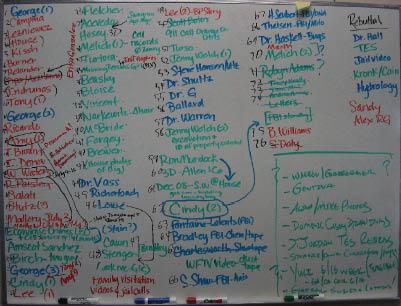

This was the white dry-erase board that we used to help us organize and get prepared for the trial. Everything from setting up our order of witnesses and structuring our argument was mapped here.

This shot of me, Frank, and the defense team was taken during the jury selection at the Pinellas County Criminal Justice Center. From left to right: me, Frank, Jose Baez, and Cheney Mason.

Used with permission of the

Orlando Sentinel,

© 2011

In this photo from the trial, Linda, Frank, and I are sifting through the garbage that was in the back of the Pontiac so that I could counter a point made by a defense witness who had testified that there was an actual piece of meat in the garbage. As I quickly pointed out, what he was calling a piece of meat was just a piece of paper—nothing that could have produced the strong odor found in the car.

Used with permission of the

Orlando Sentinel,

© 2011

A shot of the team taken at my retirement party. Unfortunately, Frank wasn’t able to make it. I’d put off my retirement for six months to see this trial through until the end, and I couldn’t have found a finer group of people to do it with. As much as it didn’t end how I would have liked, I was ready to move on (from left to right: Yuri Melich, Linda, me, John Allen).

Photograph by Rita Brockway Ashton

At this point, I don’t think we’ll ever find out what really happened that night. As I’ve revisited the verdict in the months since, I think somewhere along the way everyone—from Cindy and George Anthony to the media to the people trying the case—lost sight of Caylee. That, along with her death, is perhaps the greatest tragedy of all.

DEALING IN FORENSICS

A

fter getting word from Linda that I was on the case, my first call was to Arpad Vass, a forensic anthropologist at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, where many of the country’s scientific breakthroughs occur. Vass, an expert in the odor of decomposition, was in the process of developing a standard for decomposition odor analysis, or DOA. This standard was being designed to help identify the more than four hundred chemical compounds that emanate from a decaying human body. I needed to know if he thought his new technology could be of help in determining whether the odor in the Pontiac was undeniably that of human decomposition.

Prior to my conversation with Dr. Vass, I reviewed some of his published writing so that I wouldn’t sound like a complete moron when we spoke. His work is based on the principle that all odors are simply combinations of different chemical compounds released into the air through chemical and/or biological reactions. Some of those compounds are detectable by human beings, and we perceive them as smells. My mom’s spaghetti, the odor of which is instantly recognizable to me, is simply a group of chemical compounds in a certain concentration that my brain has learned to interpret, recall, and react to. Similarly (and I hope Mom forgives my use of her delicious spaghetti in this analogy), the odor given off by a human body during decomposition—which, if you have ever experienced it, is instantly recognizable—is also simply a combination of chemical compounds.

The challenge of the work is that our brains can’t distinguish individual compounds in the odors themselves. The goal of Vass’s work is to determine which compounds are most common. Once those compounds can be determined, a device can be developed to detect them in the air, in much the same way machines at the airport examine our luggage for the presence of compounds found in explosives. It was the first part of his research, the isolation of the common compounds, that had potential application to this case.

When I reached Dr. Vass at his office, he was happy to talk science, but he did not warm to the idea of testifying. It was out of his comfort zone. He had testified only once before, sixteen years earlier, in a case based on the chemical analysis of soil near a body, called postmortem interval testing. I recall him repeatedly telling me that the thought of testifying was not making him feel “warm and fuzzy.” I liked him from the beginning.

Dr. Vass was an unapologetic science geek. He pursued scientific investigation for the pure fascination of it, loved solving scientific problems, and discussed them with an addictive passion. Speaking with a slight affect, a disarming quality that made him accessible, he seemed to me very atypical of a forensics expert. I have dealt with forensic experts for decades, good ones and bad ones, honest ones and dishonest ones. Regardless of their reliability, one thing that these experts usually have in common is that they’re applying the research of other experts to forensics problems. Rarely had I worked with a forensics expert like Dr. Vass, a man who had actually invented the process of which he spoke. True scientific innovation is rare in professional expert witnesses.