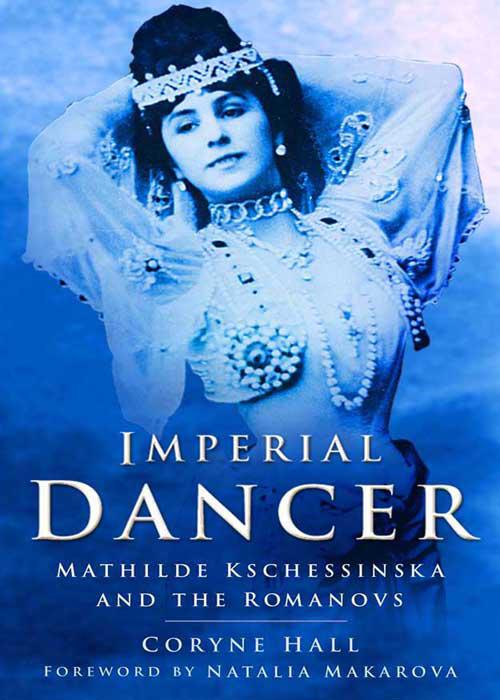

Imperial Dancer: Mathilde Kschessinska and the Romanovs

Read Imperial Dancer: Mathilde Kschessinska and the Romanovs Online

Authors: Coryne Hall

To the memory of my parents Peggy and Ernie Bawcombe; and to the memory of Theo Aronson, whose books were such an inspiration.

C

ONTENTS

Introduction: Myth or Reality?

2

‘Madly … in Love with Little K’

8

‘Danced Your Way to a Palace’

9

‘The Black-eyed She-Devil of the Ballet’

10

‘The Wealthiest Woman on the Stage’

15

The Queen of Russian Ballet

I

t has been said that Mathilde Kschessinska ‘loved ballet in general and life in particular’. On the contrary: she loved ballet in particular and life in general. She certainly led an exciting life. It was an era of true glamour in Russia among the elite. Through her royal liaisons first with Tsarevich Nicholas and later with other members of the Romanov family, Kschessinska secured her position as the reigning Prima Ballerina

assoluta

of the Maryinsky Theatre. The best of her success as a woman was her charm, femininity and inexhaustible sense of flirtation whether with men or an audience. This quality combined with her determination and the incredible energy that she put into her training to achieve her virtuoso technique justified her ballerina status. She was considered to be ‘a

terre-à-terre

dancer, without much elevation, but quick in movement, dazzling in her pirouettes and bubbling over with smiles and charm. She once danced thirty-two fouettés and after a storm of applause, sweetly danced thirty-two more.’ Kschessinska’s life still fascinates people because in our modern time there is a lack of that kind of elegance, grandeur and particularly the mystique of glamour.

Mathilde was a unique figure not only in ballet, but in Russian history as well. Even at an early age, her outgoing personality made an impression on royalty. As a student she was described as ‘small, pretty, vivacious and self-confident’. After her graduation performance from the Imperial school, Emperor Alexander, who was in attendance with his family including Tsarevich Nicholas, summoned her. As she curtseyed to the Emperor, he proclaimed ‘Be the glory and adornment of our ballet.’ Indeed that is what she became.

In my time at the Vaganova Ballet School, during the Soviet period, little was said about the legendary Kschessinska. Her affiliations with the Romanovs and her extravagant lifestyle were a taboo subject. We heard the stories that Diaghilev once created a blue costume for her to match her sapphires, but that seemed unimaginable. Our school library had photos of Spessivsteva, Pavlova and Karsavina but I don’t remember any pictures of Kschessinska. Who would think that in later years that I would choose to stay in the West and my photos would be

taken off the walls of the Vaganova School and my name, too, removed from the history books? When I returned to the Soviet Union after nineteen years of exile to perform once again at the Maryinsky Theatre, I was presented on stage with a wonderful statuette of Kschessinska in her Esmeralda costume with a replica of her pet goat. (Esmeralda was one of her most famous roles and she used to bring her goat on stage in the performance.)

I have often been asked whether Kschessinska left me a crown that Nicholas II had given her. I wonder how these rumours begin. It seems there are not many people left in the ballet world that have met Mathilde Felixovna Kschessinska. I was lucky enough to have spent time with her. Either that means I am of a certain age or I was very young when I met her. (I was very young, of course.) It certainly was a memorable occasion for me when Serge Lifar took me to see her. Hopefully you will continue to read this comprehensive biography of Kschessinska’s fascinating life and you will get to p. 300 where I describe our dinner together. I would like to add that at the end of the evening, as I was leaving, she tried to curtsey. A bit tipsy, she almost lost her balance. But she quickly regained her composure. Gracious, looking pretty with pearls around her forehead, her eyes still sparkling and mischievous, even in her nineties, she bade me farewell.

I do not believe that Kschessinska’s success was only based on her love of power and diamonds. Yes, she could be irresistible to those she wished to please, but it didn’t just come from charm. She had virtuosity, technique, artistry and great magnetism. In retrospect, when a person has everything and suddenly they are left with nothing (as after the Revolution) it is their will to survive that keeps them going. Mathilde Kschessinska had such a strong will. She decided to enjoy her life regardless of the circumstances and she survived with dignity. In her youth she said to her father ‘I want to experience all the happiness I am allowed’ – and she did.

Natalia Makarova

T

here are several people who were involved in this project at the outset and it is fair to say that without their help during the initial stages the book would probably never have been written.

First of all, my thanks to Dr Stephen de Angelis, for invaluable research materials, photographs, and help with the diary entries of Nicholas II; Senta Driver, for assistance with the American archives and who undertook all the research in the Harvard Theatre Collection; Natalia Stewart who, in between her job at the Royal Opera House, translated all the Russian letters as well as providing comments and explanations; Dr Zinaida Peregudova of the State Archives of the Russian Federation for providing, and permitting me to quote from, unpublished material; Beryl Morina, Chief Examiner, Classical Ballet (Russian Method Branch), NATD, for her personal recollections of Mathilde; Barbara Gregory, for permission to quote from the works of John Gregory, whose book

Nicholas Legat, Heritage of a Ballet Master

(Dance Books, 1978) remains the standard work; Professor Tim Scholl, for generously allowing me to quote from his AATSEEL Conference Paper based on his own archival research into Kschessinska’s early diaries and memoirs; Katrina Warne for the loan of Russian books; and Paul Kulikovsky, who gave me the video which finally convinced me to write the book.

I was privileged to spend two days in the home of the late Lady Menuhin, going through the Kschessinska letters in the Menuhin archives. I would like to express my gratitude to the heirs of Lady Menuhin for allowing me to see these letters, and to Susanne Baumgarten of the Menuhin archives for facilitating this. Unfortunately, the letters were sold at auction before the book was completed and it has not been possible to make contact with the new owner(s). I have therefore used information from the letters without quoting from the text.

To my great regret, and despite the best efforts of several people in Spain, no reply was received to my request for access to the archives held by Grand Duke Andrei’s family.

Nevertheless, this book would not have been possible without the help of a large number of people and I would like to express my thanks to everyone listed below. Others have asked to remain anonymous and in respecting their wishes my gratitude is no less great.

In Britain:

Leonard Bartle, the National Arts Education Archive; Eunice Biedryski Bartell, President, The Russian Ballet Society; Mary Clarke, editor,

The Dancing Times

; Joy and Graeme Cruickshank, Theatre Information Group/Society for Dance Research; Richard Davis, Archivist, The Brotherton Library, Leeds University; Diana de Courcy-Ireland; Express Newspapers; Nigel Grant, Dance Teachers On-line; Jonathan Gray and the staff of the Theatre Museum; Paul Grove; Jane Jackson and the staff of the Royal Opera House Archives; Chris Jones, National Resource Centre for Dance; Sonja Kielty; Ian Lilburn; Nesta MacDonald; Natalia Makarova; Lady Rose McLaren; Mikhail Messerer, Company Guest Ballet Teacher, The Royal Ballet; Ann Morrow; James Munson; Bridget Paine and the staff of Bordon Library; Portsmouth Library; Carol Relf; Ian Shapiro, Argyll-Etkin Ltd; Roger Short; Karen Stringer; The London Library; Richard Thornton; Dawn Tudor; Moya Vahey, Chairman, The Legat Foundation; John Van der Kiste; Hugo Vickers; Mollie Whittaker-Axon; John Wimbles; Sue and Mike Woolmans; Marion Wynn; Charlotte Zeepvat; and Frank Taylor of Interworld for his forbearance.

In Denmark:

Anne Dyhr, Det Kongelige Bibliotek; Anna Lerche von Lowzow and Marcus Mandal, Nordisk Film TV; Ove Mogensen; Stig Nielsen.

In Finland:

Ragnar Backström; Jorma and Païvi Tuomi-Nikula.

In France:

Jacques Ferrand; Mme Ivanov; Elisabeth Roussel; Marina von Isenberg.

In Germany:

Professor Dr Eckhard G. Franz, Hessisches Staatsarkiv, Darmstadt.

In Norway:

Trond Norén Isaksen.

In Russia:

Olga Barkovets; Zoia Belyakova; Elizabeth Kulazhenkova; Linda Predovsky; Elena Yablochkina.

In Spain:

The Archives of the Fundación Infantes Duques de Montpensier; Ricardo Mateos Sainz de Medrano; HRH Princess Beatrice of Orleans-Borbòn; HH Prince Michel Romanoff; José Luis Sampedro.

In Sweden:

Tove Henningson; Pamela Moberg; Ted Rosvall.

In Switzerland:

The Bibliotek St Moritz; Dominique Nicolas Godat, The Kulm Hotel, St Moritz; HH Prince Nicholas Romanov; Karen Roth-Nicholls.

In the United States of America:

Mark Andersen; Arturo Beéche, Eurohistory.com; Ronald Bulatoff, The Hoover Institution Archives; Marlene A. Eilers-Koenig; Georgia Hiden; Greg King; Peter Kurth; David McIntosh; Madeleine Nicols (Curator) and Charles Perrier, The New York Public Library Dance Division; Krista Sigler; Stephen Stephanou; Nancy Tryon; Frederic Woodbridge Wilson (Curator), Irina Klyagin and Kathleen Coleman, The Harvard Theatre Collection.

Finally, thanks to my editors at Sutton Publishing, Jaqueline Mitchell and Anne Bennett, for all their hard work in seeing through this book from planning to completion.