In the Catskills: A Century of Jewish Experience in "The Mountains" (26 page)

Read In the Catskills: A Century of Jewish Experience in "The Mountains" Online

Authors: Phil Brown

Tags: #Social Science/Popular Culture

Old hotel, now private home, Ulster Heights, 2000. Many old hotels are now the residences of individuals. Ulster Heights has an especially large number of them. P

HIL

B

ROWN

Comparison of small and large hotels. The owners and staff in the kitchen of the Maple Court Hotel, Dairyland, 1941. This small hotel had a maximum capacity of eighty guests and was clearly run with a very small labor force, though they certainly worked hard.

A

LICE

G

UTTER

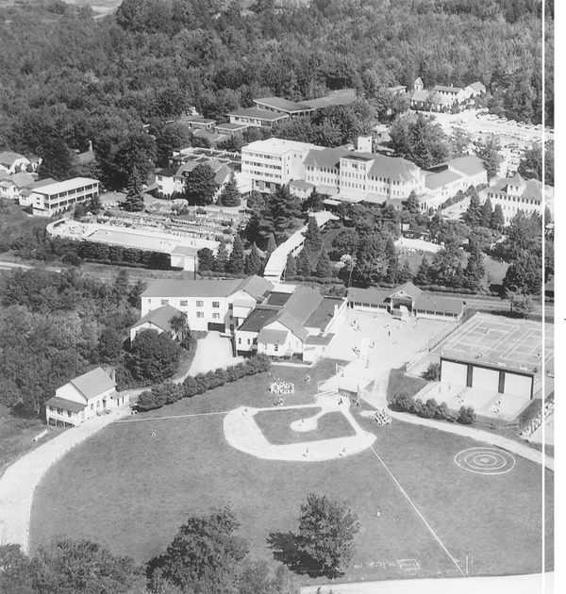

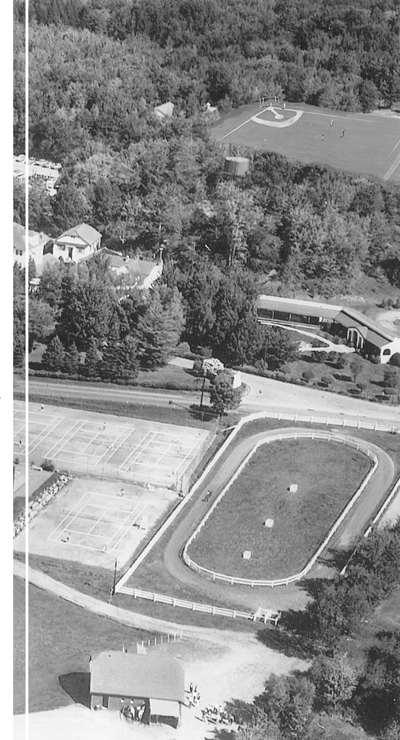

Brickman Hotel, South Fallsburg, 1960s. In contrast to the Maple Court, Brickman’s could hold about 750 people. It had two baseball fields, a dozen tennis courts, and a riding academy. The aerial view shows much of the original shape, despite extensive modernization. B

EBE

T

OOR

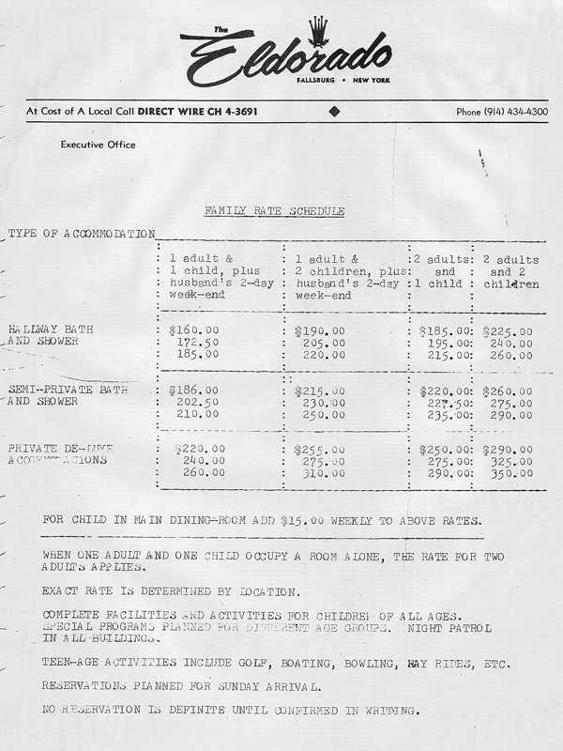

Rate sheet for Eldorado, Fallsburg, 1960s. The prevalence of weekend husbands can be seen in the rate categories. This medium-sized hotel could hold perhaps 300 people. C

ATSKILLS

I

NSTITUTE

C

atskills hotelkeepers pioneered the all-inclusive vacation, with three meals plus a nighttime tea room, entertainment, many sports and activities, and eventually day camps for children. Because they often began as boarding houses and small family-style hotels, even larger hotels retained a certain intimate feeling. The owners were always present, often as a pair of in-law couples, and they all worked in various capacities. They mingled with guests, many of whom were relatives, friends, and acquaintances, and provided a familial environment. This milieu was safe but also contained the pros and cons of intimate contact. More than 1,000 boarding houses and hotels existed over the century, the latter making up the vast majority. At least 500 operated at any one time, and they ranged from small places holding 40 people to large ones with 500–900 guests, Grossinger’s with more than 1,000, and the Concord with 2,000.

Abraham Cahan, founder of the

Jewish Daily Forward

newspaper, was one of the major Jewish writers in the early decades of the twentieth century. His 1917 novel,

The Rise of David Levinsky

, was the first piece of fiction to take up the Catskills. This excerpt, “Dinner at the Rigi Kulm House,” is a literary look at the life of an elegant Catskills hotel and its elaborate food, served to the accompaniment of a band. Cahan captures the tumult of the dining rooms, even in this fine hotel, that can still be observed today.

Hortense Calisher’s short story “Old Stock” is unique in telling the story of a Jewish family at a Gentile-owned boarding house that now has Jewish clientele. German Jews who have recently had a financial downturn, this family is displeased at staying with Eastern European Jews. That conflict was significant throughout America, and clearly in the Catskills, where German Jews typically stayed in a different area, around Fleischmann’s. Calisher’s fifteen-year-old protagonist, Hester Elkin, and her mother visit a nearby woman they have come to know, but are surprised to hear this neighbor of Dutch descent make an anti-Semitic remark, apparently unaware of her guests’ background. That casts a shadow on Hester’s vacation, as she keeps expecting anti-Semitism to surface in others at the boarding house.

“Young Workers in the Hotels,” an excerpt from my

Catskill Culture: A Mountain Rat’s Memories of the Great Jewish Resort Area

, is a description of my own and other young workers’ experiences as waiters, busboys, bellhops, and counselors. I describe our work life, the staff quarters, ways we entertained ourselves, and the importance of this experience in terms of both income and learning key work skills.

Eileen Pollack’s “The Pool” comes from her novel

Paradise, New York

, in which young Lucy grows up in her grandparents’ and parents’ hotel. Later, when her grandmother is trying to sell it to Hasidim, Lucy tries to salvage it. While not autobiographical, Pollack’s novel draws on her experience in the hotel business until she left for college. In this excerpt, nine-year-old Lucy describes her life as an owner’s child, using the pool setting to examine her fascination with the dining room staff and observe the guests.

Tania Grossinger’s “Growing up at Grossinger’s” derives from her book of the same title. Grossinger’s mother, a relative of the Grossingers who owned the famous resort, worked as the social hostess there for many years. This gave Tania a wonderful insight into the workings of the hotel, and she treats us to a glimpse of the famous entertainers who played there and of how the staff lived and entertained themselves.

Sidney Offit’s “Five and Three House” comes from his 1959 novel

He Had It Made

, just republished in 1999. Offit’s original title for his book was

Five and Three House

, but it was changed before publication. “Five and three” refers to the typical tip level of the hotel—five dollars a week for the waiter and three for the busboy. The lead character, Al Brodie, talks himself into a waiter’s job and makes his way as best he can in the tense atmosphere. Offit presents the best account yet of life in the dining room and kitchen, full of humor and sex.

Jerry Jacobs wrote “Reflections on the Delmar Hotel and the Demise of the Catskills” especially for this anthology. Jacobs is a sociologist whose family owned a small hotel near Liberty, and who only later in life came to realize that his experiences there were worthy of sociological attention. He notes that most of the Jewish academics he knows have no interest in studying Jewish life, and that this has meant that we have hardly any exploration or documentation of the importance of this unique culture. He provides a vivid view of the inside of the hotel business, including the many different jobs he had; explores some of the reasons for the decline of the Catskills; and mourns the loss of the sense of community it provided.

D

inner at the Rigi Kulm on a Saturday evening was not merely a meal. It was, in addition, or chiefly, a great social function and a gown contest.

The band was playing. As each matron or girl made her appearance in the vast dining-room the female boarders already seated would look her over with feverish interest, comparing her gown and diamonds with their own. It was as though it were especially for this parade of dresses and finery that the band was playing. As the women came trooping in, arrayed for the exhibition, some timid, others brazenly self-confident, they seemed to be marching in time to the music, like so many chorus-girls tripping before a theater audience, or like a procession of model-girls at a style-display in a big department store. Many of the women strutted affectedly, with “refined” mien. Indeed, I knew that most of them had a feeling as though wearing a hundred-and-fifty-dollar dress was in itself culture and education.

Mrs. Kalch kept talking to me, now aloud, now in whispers. She was passing judgment on the gowns and incidentally initiating me into some of the innermost details of the gown race. It appeared that the women kept tab on one another’s dresses, shirt-waists, shoes, ribbons, pins, earrings. She pointed out two matrons who had never been seen twice in the same dress, waist, or skirt, although they had lived in the hotel for more than five weeks. Of one woman she informed me that she could afford to wear a new gown every hour in the year, but that she was “too big a slob to dress up and too lazy to undress even when she went to bed”; of another, that she would owe her grocer and butcher rather than go to the country with less than ten big trunks full of duds; of a third, that she was repeatedly threatening to leave the hotel because its bills of fare were typewritten, whereas “for the money she paid she could go to a place with printed menu-cards.”

“Must have been brought up on printed menu-cards,” one of the other women at our table commented, with a laugh.

“That’s right,” Mrs. Kalch assented, appreciatively. “I could not say whether her father was a horse-driver or stoker in a bath-house, but I do know that her husband kept a coal-and-ice cellar a few years ago.”

“That’ll do,” her bewhiskered husband snarled. “It’s about time you gave your tongue a rest.”

Auntie Yetta’s golden teeth glittered good-humoredly. The next instant she called my attention to a woman who was driven to despair by the superiority of her “bosom friend’s” gowns, had gone to the city for a fortnight, ostensibly to look for a new flat, but in reality to replenish her wardrobe. She had just returned, on the big “husband train,” and now “her bosom friend won’t be able to eat or sleep trying to guess what kind of dresses she brought back.”

Nor was this the only kind of gossip upon which Mrs. Kalch regaled me. She told me, for example, of some sensational discoveries made by several boarders regarding a certain mother of five children, of her sister who was “not a bit better,” and of a couple who were supposed to be man and wife, but who seemed to be “somebody else’s man and somebody else’s wife.”

At last Miss Tevkin and Miss Siegel entered the dining room. Something like a thrill passed through me. I felt like exclaiming, “At last!”

“That’s the one I met you with, isn’t it? Not bad-looking,” said Mrs. Kalch.

“Which do you mean?”

“‘Which do you mean’! The tall one, of course; the one you were so sweet on. Not the dwarf with the horse face.”