In the Catskills: A Century of Jewish Experience in "The Mountains" (3 page)

Read In the Catskills: A Century of Jewish Experience in "The Mountains" Online

Authors: Phil Brown

Tags: #Social Science/Popular Culture

Abandoned chicken farm, Glen Wild, 1998. Farming provided the basis for the first Jewish settlement in the Catskills. Dairy farming was not very successful, but farmers raising poultry and eggs fared better. In the 1950s and 1960s, Sullivan County produced more eggs than any other county in the state. Farmers began taking in boarders very early on, often continuing to operate their farms while the guests enjoyed the country. Many hotels and bungalow colonies grew from such humble origins. P

HIL

B

ROWN

Hotel and bungalow colony signs. Roads and highways were full of individual billboards, but large signboards like this were also common, since there were so many hotels and bungalow colonies.

E

ILEEN

K

ALTER

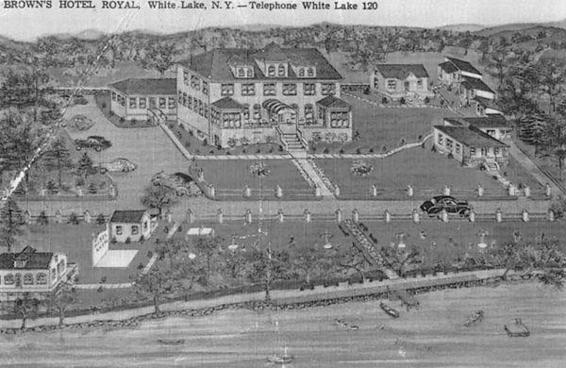

Brown’s Hotel Royal, White Lake. William and Sylvia Brown owned this hotel from 1946 to 1952. Phil Brown has been in touch with the family of the man who sold it to them as well as two subsequent owners, including the present owners of the Royal’s current incarnation, the Bradstan Country Inn. This card is by Alfred Landis, the most artistic of all postcard printers. P

HIL

B

ROWN

The Main House at the Seven Gables Hotel, Greenfield Park, 1952. Sylvia Brown was chef at the Seven Gables from 1955 to 1960, and it is the hotel that was the most formative in Phil Brown’s life in the Catskills. F

RANK

D

APSKI

William Brown in front of the casino at the Seven Gables. For a couple of years he ran the concession, located in the casino, and Phil Brown helped out, young as he was. P

HIL

B

ROWN

From ruin to renewal. The pool at the Grand Mountain Hotel, Greenfield Park, went from a weed-overgrown wreck in 1999 to a beautiful, appealing pool in 2000. There have been a few revivals of small and medium-size hotels. The Grand Mountain probably held 250 guests, and in the 1960s was famous for its late-show strippers.

P

HIL

BROWN

T

he history of the Jewish Catskills really starts on the farms. Baron de Hirsch, a major Jewish philanthropist, funded many agricultural projects that put Jews onto farms in places such as Argentina, South Dakota, Saskatchewan, New Jersey, and the Catskills. From the first years of the twentieth century, the farms of Ulster and Sullivan counties were a major part of the early Jewish settlement there, providing a year-round Jewish population base and the building and support of synagogues. These were primarily dairy and chicken farms, since not much else grew well in the region. In the middle of the twentieth century, Sullivan County led the state in egg production. The long-term impact of the farms was their taking in boarders to supplement their meager income. Some farmers decided to make the boarding business their main enterprise. Once the boarding house was established, it might develop along one of two routes. Some became kuchalayns (boarding houses where renters shared kitchen facilities), which frequently transformed into bungalow colonies. Others became hotels (as did some kuchalayns later). These transformations will be the subject of the following two sections. Here, we focus on the origins of the farms and offer some glimpses of the impact of World War II and the Holocaust on local life and on resorts.

Phil Brown’s opening essay, “Sleeping in My Parents’ Hotel,” sets the stage for this collection. Through his account of sleeping in the current incarnation of what had been his parents’ hotel in the 1940s and 1950s, he notes the themes that shape the book.

Abraham Lavender and Clarence Steinberg’s selection, “Jewish Farmers of the Catskills,” comes from their book of that title, a masterful study from documents, interviews, and personal experience. They offer a slice of farm life, the challenges farmers faced, the support they got from the Jewish Agricultural Society, and their importance in the local Jewish community. Clarence Steinberg grew up on a farm in Ellenville and later worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, so he well understands the legacy of the Jewish farmers.

Reuben Wallenrod’s “Hotels and the Holocaust” comes from

Dusk in the Catskills

, his novel tracing the seasonal life of a small hotel modeled on Rosenblatt’s Hotel in Glen Wild, where Wallenrod often stayed. This excerpt illustrates the conflict between having a good time on vacation and the reality of the massacre of Jews in Nazi Europe.

Martin Boris, in “The Catskills at the End of World War II,” also addresses this era, but right after the war and with reference to local residents. This is an excerpt from his

Woodridge 1946

, which centers on Our Place, a Woodridge restaurant, and its owners, workers, and customers. Among other things, Boris deals with conflicts between traditional religious traditions and leftist politics. Indeed, this book is one of the few writings we have about communist and socialist activities in the Catskills.

Sleeping in My Parents’ Hotel:

The End of a Century of the Jewish Catskills

O

n beautiful August 3, 1998, I was sleeping in my parents’ old hotel in the Catskills. A half century ago, that would have been pretty unremarkable, but William and Sylvia Brown owned Brown’s Hotel Royal on White Lake only from 1946 to 1952. It’s a miracle the place still stands, recycled as the Bradstan Country Hotel and beautifully detailed with luxurious antiques and appointments far exceeding an old Catskills hotel. Most small hotels—the Royal would be stuffed at 60 guests—long ago collapsed, burned, or simply were reclaimed by the land. For my book,

Catskill Culture

, I compiled a list of 926 hotels (subsequently expanded to 1,094 on the Catskills Institute Web site) that graced the Jewish summer paradise of Sullivan and Ulster counties over the last century. Less than two handfuls remain, none of them as small as the Royal, and they close at an alarming rate.

That’s why the Royal’s survival is so spectacular. I “found” it in 1993, on my first field trip to the Catskills, after having stayed away since 1979. Like many others who worked hard in the Catskills or who tired of the culture, I fled after finishing college. It took many years to integrate into my adult life the ambivalence that I had always experienced there. I had been uprooted every year in May from school and friends to go there and live with my parents in cramped rooms. I watched my parents work extremely hard each summer, three months’ labor with not a single day off. We never had our own summer vacation, but only served other people on theirs. Also, like many others, I fled from the strong Jewish culture of the area, not knowing until recently how to make sense of it.

I say that I “found” the Royal because my parents, until they died—my father in 1972, my mother in 1991—hid from me their failed venture into the hotel business. Certainly, they had told me that they once had a hotel, when I was born. They even showed me some photos of us there. But they said the hotel was “gone.” Surely they knew it still stood, in various reincarnations, including a seedy rooming house, since they worked the Catskills their whole lives and knew an enormous number of people and places there. My father died working in his coffee shop concession at Chaits Hotel in Accord, and my mother remained cooking there till 1979. For many of their years working in Swan Lake, they drove right past White Lake en route to Monticello. My father often worked for Dependable Employment Agency, driving new hires all over the Mountains, so he would undoubtedly have passed it many times. And nowhere was that far that they couldn’t have shown me their old hotel, especially since I often asked. All I ever got was, “It’s gone,” even when we spent several weeks in May on the Kauneonga side of White Lake at our friends George and Miriam Shapiro’s bungalow colony while my parents looked for work.