Incense Magick (20 page)

Authors: Carl F. Neal

Tags: #incense, #magick, #senses, #magic, #pellets, #seals, #charcoal, #meditation, #rituals, #games, #burning, #burning methods, #chaining, #smudging, #herbal blends, #natural, #all-natural

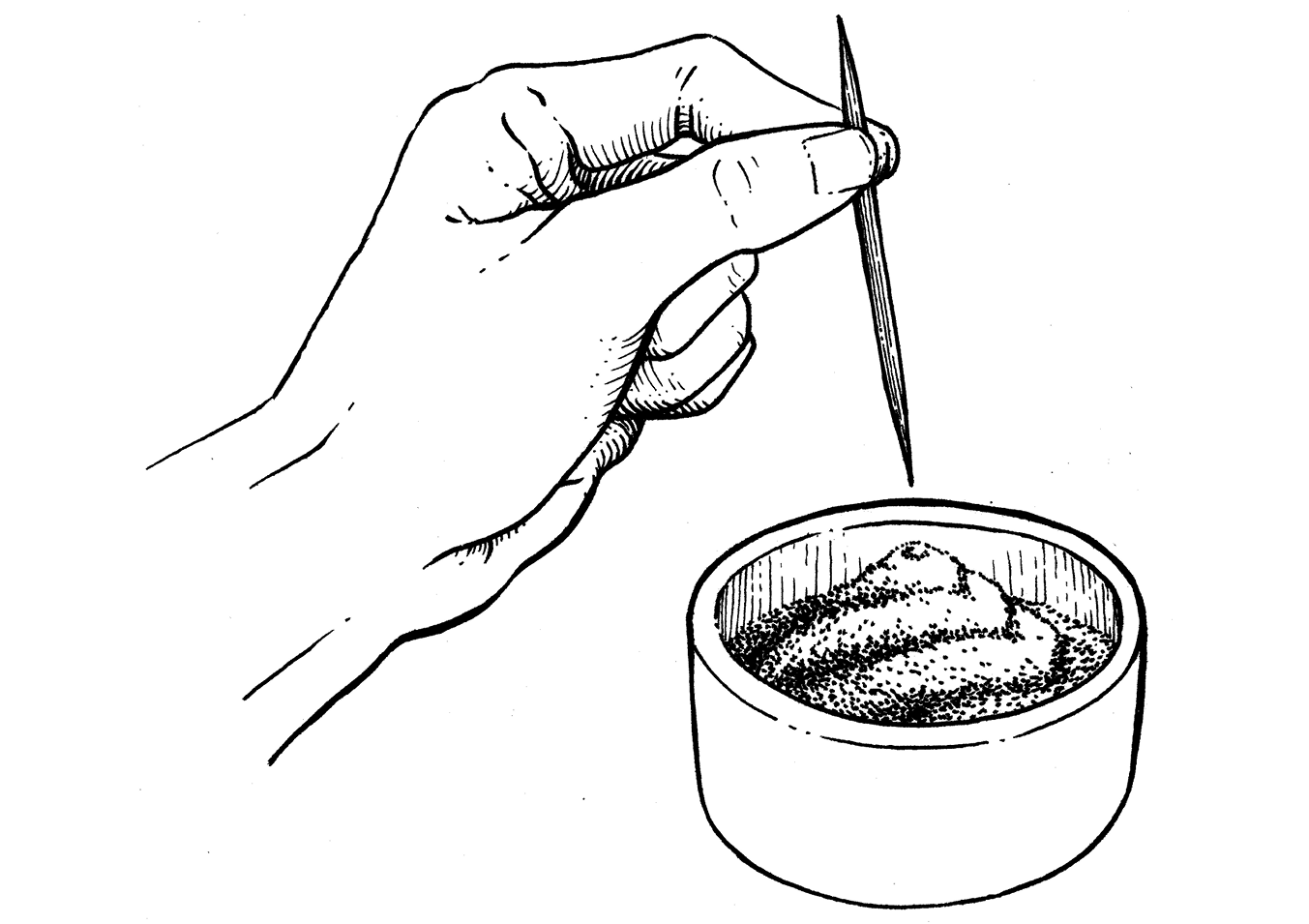

Piercing the volcano with a toothpick.

Place the Plate

Once the hole is pushed into the volcano, the mica plate can be placed on the top. The mica should be placed directly over the hole in the volcano. If no mica plate is available, a small ceramic tile or metal plate may be substituted. In a pinch, even a small square of aluminum foil could be used. The plate rests over the hole, which is directly above the charcoal. This means the heat will travel upward to the plate, creating indirect heat for your aromatics. Once all the elements are in place, you will have great control over the heat in your censer. If you find that the plate is not heating enough, you can gently push it down farther into the ash volcano. If you find that it is too hot, you can remove the plate, add a tiny bit of ash to the top of the volcano and replace the plate or, more simply, remove the plate and use your skewer to push the charcoal down a bit more into the ash, and then replace the plate. The farther apart the charcoal and the plate rest, the cooler the plate will be. The closer the two rest, the warmer the plate will become.

Using this approach for loose incense will allow you to get the most from every aromatic you burn. It gives you great control over the heat applied to the aromatics, keeps smoke to an absolute minimum and produces the purest scent possible short of creating joss sticks or cones. Although the technique seems elaborate, it is actually fairly simple once you become familiar with it.

Listening to Incense

What has been discussed so far is strictly part of the mechanical aspects of this Asian technique. This is, in fact, the least important factor when you examine the heart of kodo and kodo-inspired incense burning styles. The most important aspect of kodo, at least from some perspectives, is touching the power of the amazing aromatics. These incense materials are so revered that the experience transcends merely smelling the incense. The Japanese teach a tradition of “listening to” incense. While it may seem an odd way to look at things, with further thought and experience you will learn that there is a tremendous amount to be said for this approach to most areas of your incense use.

I have taught all of my students to use incense burning as an opportunity to learn and grow. I always reinforce the idea that no particular traditional association or practice will work for everyone, and if it does it may not work in the same way. I encourage everyone to begin building their “incense vocabulary” by taking time to sit with single ingredients and “listening” to what that aromatic has to say. If you still your mind and allow yourself to hear, aromatics will whisper their secrets to you. When I learned of the terminology used in kodo that described exactly what I had taught for years, I knew that this form of art had truly deep roots.

Deep Reverence for Incense

At the heart of kodo and related adaptations is the deepest respect for every part of the ritual and true reverence for the rare woods used in kodo. When the koro is passed in the kodo ceremony, some participants will turn their heads and place their ear to the mouth of the koro. This is a demonstration of reverence and is a physical action that reflects the spirit of the idea that they are listening to the incense. It is further proof that magick can flow in both directions with regards to the physical world: our physical actions can impact what we do on an energetic level, and magickal energies can shape actions in the physical dimensions.

All participants in kodo-style incense ceremonies are attentive and very respectful of one another and the process from beginning to end. The organizer is treated with impeccable manners and is likewise an extremely attentive host. Even in the far-less-formal “incense games,” the level of decorum is far higher than is commonly found in kodo-inspired activities here in the West.

A Group Activity

Kodo, and most of the other activities kodo has inspired, are intended to be group activities. There are several reasons for this. An obvious one is the social nature of incense events. Not only does it allow one to host a very special (and expensive) party for the pleasure of friends, it serves as a way to display wealth in the materials used. It is also a way to show status based on those who attend your party and your access to special materials. At one time kodo was considered a necessary skill for any Japanese gentleman. Kodo gatherings, or even game nights, demonstrate your own skills to others.

On a more important level, the materials used in kodo and games are often expensive because high-quality aloeswood is quite rare. Not only is it a waste of money to hold these materials for only one person, it is also selfish. Eight people can enjoy a sampling of aloeswood just as easily as one person. It costs no more to share your incense with your friends, so why not allow them to enjoy this rare bit of beauty from nature? I think that all of those points are just as valid today as they ever were. I'm not suggesting that you never burn incense when you're alone, but any time you have a rare scent from the natural world, please share it with others. It is one way that Mother Earth speaks to her children. I hope you won't keep that message to yourself.

Study, Rituals, and Games

Kodo was once an essential part of Japanese life in the upper stratus of society. Incense use went far beyond kodo, but in some ways kodo is the ultimate elevation of incense celebration. Much like the Japanese Tea Ceremony, kodo is a precise ritual. It is studied as an art and a science, and its study survives into the twenty-first century.

Formal Incense Study

While the kodo schools are not nearly as large as they were in antiquity, many of them still exist. An avid student can spend years perfecting the techniques required to perform the kodo ceremony correctly. When I talk about kodo schools, I mean it in much the same way we would discuss martial arts schools. Some schools have their own variations on the ceremony or possibly the materials used. The essentials are the same, but the details may vary. If this is something that speaks to you, I suggest you read more about kodo and even look for one of the schools. They periodically hold in-person seminars and offer coaching in person or via electronic methods. Participating with these groups is also a great way to attend a formal kodo ritual.

Detailed Ritual

I have already offered one disclaimer, but I feel compelled to offer an additional one: I am no expert in kodo, and what I offer here is a reinterpretation of the kodo ceremony through the eyes of a Neopagan author. If you enjoy the kodo approach, as I do, you should seek proper training in the art if you want to perform an accurate ceremony. Fortunately for the rest of us, we can adapt techniques and philosophies to fit within our normal incense framework. I believe a great starting place would be Kiyoko Morita's excellent book

The Book of Incense

(Kodansha International, 1992).

Specialized Tools

To be a true practitioner of kodo, you need a proper set of tools. Those of us who aren't such precise practitioners substitute items for the traditional tools, but you should locate a set of the real thing in order to conduct a formal kodo ceremony. They aren't horribly expensive and are available from several different retailers in the United States. The traditional tools include a pair of wooden and a pair of metal chopsticks. The wooden ones are used for handling small pieces of aromatic wood, while the metals ones are used for handling charcoal and ash. Silver tweezers are used to handle mica plates, and an ash press is needed to shape the volcano. A tiny broom is required to keep the edge of your censer clean, and an incense spoon can be used to handle aromatics as well.

Kodo tool sets are sometimes given as gifts to kodo aficionados but they make a great gift for yourself as well. If you want to try some kodo techniques but would rather hold off on the expense of purchasing a tool set immediately, you can use some less-expensive substitutes. If you look around your home, you will likely find viable options to replace the traditional tools. Clearly you don't have to use silver tweezers since the ones in your medicine cabinet will serve the purpose. While pliers are one substitute for tongs, an inexpensive nutcracker (two rods of metal that are hinged together at the top) works pretty well too. Wooden chopsticks (even bone or plastic) are easily located, and very inexpensive ones can be found in many grocery stores. While not ideal for handling charcoal, a large pair of tweezers can also work. Any small, clean paint brush will serve to replace the feather brush, and many letter openers and butter knives (as suggested by Kiyoko Morita) will work as an ash press.

Censer Preparation

In addition to the “nuts and bolts” of censer preparation I discussed earlier in this chapter, there is also an aesthetic aspect to the preparation of a censer for kodo. Different formal traditions or schools mark the top of the prepared censer with a signature pattern drawn or pressed into the surface of the incense volcano. Specific books on kodo will give you the details of those patterns but, in informal use, you can create patterns in your volcano either as a personal signature or using an emblem that is important to you. Some covens have adapted this style into their own rituals and some of those use a unique pattern to denote their coven.

With the volcano being round, you can take advantage of this and use decorations on it just as you would a circle of symbols on paper or other mediums. Conversely, you could treat it as a reflection of a magick circle and mark the four quarters with appropriate symbols. Adapt this method to your own practices in whatever way you see fit. If you can imagine something, you can impress those thoughts into the surface of your volcano.

Many aspects of censer preparation, seating arrangements, and more are part of the ritual of kodo. A table is prepared so that all the participants can sit comfortably around it, near enough to pass the censer. Traditionally, the master of ceremonies will sit at the central position with an assistant beside her. The master will place a clean mica plate on the top of the volcano and add a single splinter of aloeswood to it. The censer (koro) is passed to the master's left. Each participant will hold the koro with the left hand under it and the right hand cupped over the top. The participant lifts his right hand slightly so that his nose can be placed at the top of the koro. The fragrance is inhaled and enjoyed. The most respectful participants will often turn their heads and momentarily place an ear above the koro to symbolize listening to incense. Once the koro has been passed to each participant, it is handed back to the master, who replaces the mica plate with a clean one. A new type of aloeswood is added and the koro is passed again.

Incense Games

Incense games in the kodo style (called numikoh) are often created with the idea that there is no competition involved and there are no “wrong” answers. Other games can be highly competitive affairs where each guest attempts to accurately identify different kinds of aloeswood (a difficult task for any nose that is not well practiced) or even write poems or stories based on what they smell. You can certainly play the traditional games, especially as the incense knowledge of you and your guests grows. For this section, I've adapted traditional incense games into forms that might be a bit more familiar to the magickal community.

Once you grasp the basic concepts of incense games, you will see how they can be easily adapted to use in your own practices. Incense games are a great way to bring people together into a common experience that has familiarity to it. It is also a great educational opportunity. Games can be adapted for use from total novices to the most experienced herbalists.

The two sample games that follow will give you the concept of these games. You can then modify them or use them to inspire completely different games. You will know best what level and style of game will work for any given audience you might have. The games test the scent memory and palettes of each guest, but most games also contain another aspect beyond the incense.

The typical arrangement for an incense game would be to have one master of ceremonies seated at a center seat at a table (sometimes an assistant will sit to the right), and the guests will sit around the table. Incense will be prepared in a censer and passed to the entire group (clockwise, or deosil). Each participant should have a pencil and sheet of paper to record his or her answers to the game's questions. The master of ceremonies does not play in the game but still needs pencil and paper to record information as the censer is passed. Although the master of ceremonies and any assistants do not play the game, they can still enjoy the scent of each passing of the censer. The purpose of this type of game is to grow closer to others and to have fun.

Journey Across America

This game uses incense to represent a journey from one coast to the other. Four aromatics are selected for the journey and the participants will get to sample three of the scents before the game begins. You will need Western cedar wood (you could substitute any other cedar but the Western is the most appropriate), piñon, sage, and rosemary. All of the aromatics should be powdered. Ceramic tiles or mica plates are not absolutely mandatory but they are very helpful. You will also need at least one censer with prepared charcoal (using multiple censers makes the game flow more quickly and smoothly). You need to select censers that can be passed when scentless charcoal is burned inside. Obviously a Japanese koro is an ideal choice as it has a perfect shape for holding to one's nose and “listening to the incense” while remaining cool enough to easily handle. Ideally you would use two koros with prepared charcoal, the seven packets of aromatics, and seven mica plates or small ceramic tiles plus pencils and paper for everyone.