India Discovered (21 page)

It was a measure of the Taj’s uniqueness that some even suggested that its designer might have been one of the Europeans employed by Shah Jehan. This idea was, of course, anathema to Havell. It was just another example of foreigners trying to find a non-Indian inspiration for anything in Indian culture that took their fancy. Examining the literary evidence in some detail, he concluded

that even the inlay work – cornelian and agate stones embedded in the white marble in the most delicate of floral designs – was not, as was generally thought, of Italian origin. It was true that the

pietro duro

work of Florence was much in fashion at the time, but mosaic inlays had been used in India for centuries: James Tod had mentioned a Jain temple of the fifteenth century with something similar.

Besides, the records showed that the inlay artists employed on the Taj were all Hindus.

The gardens, too, which add so much to the staging of the Taj, were the work of a Hindu, from Kashmir. But on this point Havell was prepared to give ground. There was no Indian tradition of formal gardens, divided and subdivided with geometrical precision by neat paths and water courses. From the pools of

dense shade to the gay parterres and the gurgling fountains, this was an oasis legacy, the expression of a hard, warrior people’s longing for luxury and physical indulgence, a place in which to forget the austerities of the Central Asian deserts and dally with Omar Khayyam and a long glass of sherbet.

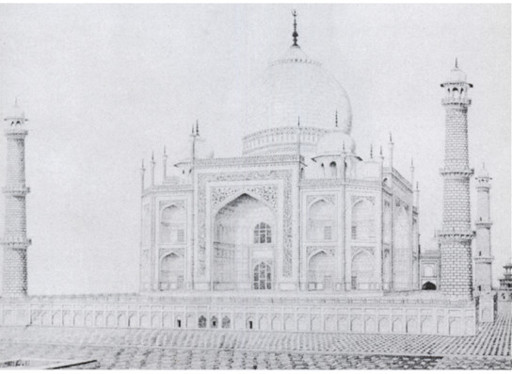

Undoubtedly the siting of the Taj Mahal has a lot to do with its unique appeal. The shady gardens

and reflecting water-courses, the flanking buildings in sober red sandstone, the dark frame of the great gateway and the backdrop of the Jumna river – all combine to make the sudden sailing into sight of the white marble mirage a dramatic experience. But it was the building itself that Havell was most interested in. He had studied the

silpa-sastras —

the traditional manuals of the Hindu builder

– and believed that even the bulbous dome conformed more closely to Indian ideals than those of Samarkand. There was even a sculptural representation of such a dome in one of the Ajanta cave temples. Moreover, the internal roofing arrangement of four domes grouped round the fifth, central, dome conformed exactly to the

panch-ratna,

the ‘five jewel’ system so common to Indian buildings of all sorts.

All this was not enough in itself to shake traditional views, but Havell was not finished. In the nineteenth century, as now, people were inclined to concentrate too much on the buildings of Delhi and nearby Agra. For most, the Pathan and Moghul styles were the sum total of Islamic architecture, because they were the ones represented in Delhi and Agra. Fergusson, of course, knew better, and devoted

considerable attention to the Islamic buildings of Gujerat, Bijapur, Gaur and elsewhere. But he made no attempt to fit these into his ‘natural sequence’ of Saracenic architecture; they were simply provincial styles, of considerable merit but no lasting significance. Havell, though, examined them much more closely and became convinced that, away from the political turmoil of north-west India,

the architectural continuity before and after the Mohammedan conquest was unbroken; and that it was from these provincial centres that the ideals and craftsmen used by Shah Jehan had been drawn. In Gujerat some of the mosques of the first Mohammedan dynasty are indistinguishable from temples; also in Gujerat, white marble had been used extensively by both Hindu and Jain. On the other side of India,

at Gaur in Bengal, the Mohammedans inherited the brick building tradition of the Hindu capital that had occupied the same site. Here there were exceptionally versatile masons, familiar with the voussoir arch. The extent to which they were subsequently employed throughout the Moghul empire can be judged by the ubiquity of curved Bengali roofs – even in the Red Fort at Agra. At Bijapur the Mohammedans

also inherited a local building tradition, for nearby lay the great Hindu capital of Vijayanagar. European accounts of Vijayanagar before its destruction only hint at its architectural wonders, but certainly the dome and the pointed arch were in general use. It was no coincidence that the great building period in Mohammedan Bijapur began immediately after the fall of Vijayanagar. Encouraged

to concentrate on the dome, the erstwhile Hindu architects produced first the Bijapur Jama Masjid and then the giant Gol Gumbaz with one of the largest domes in the world. According to Havell, it was on the skills of these master dome builders that Shah Jehan drew for the Taj Mahal.

In all this there was much speculation. It was fifty years since Fergusson had first put pen to paper, yet new

material was still being ‘religiously docketed and labelled according to his scheme’. In showing that he could have been wrong about the inspiration behind Moghul architecture, Havell sought to question the whole basis of his work. ‘The history of architecture is not, as Fergusson thought, the classification of buildings into archaeological water-tight compartments according to arbitrary ideas of

style, but a history of national life and thought.’ Its object should be the identification ‘of the distinctive qualities which constitute its Indianness, or its value in the synthesis of Indian life’.

This was certainly asking too much of a nineteenth-century art historian. But it was true enough that any scheme of classification must have its faults; and the greatest casualty of Fergusson’s

was the secular architecture of India. His classifications related primarily to religious buildings, to temples, tombs and mosques. Palaces, forts and public works were tacked onto his various classifications with little regard for their style. Hence the Rajput palaces, arguably the most impressive and certainly the most romantic group of buildings in India, were sandwiched incongruously between

the latest and least distinguished Indo-Aryan temples and a preamble on the earliest Saracenic buildings. Subsequent works, following Fergusson’s scheme, often relegate them to an appendix. For, as Havell rightly observed, there could be no argument that in secular architecture the styles of Hindu and Mohammedan, of Rajput and Moghul, were one and the same. Moreover, the origins of this style were

wholly Indian. Witness the great fifteenth-century Man Singh palace in the Gwalior fort. ‘One of the finest specimens of Hindu architecture that I have seen & the noblest specimen of Hindu domestic architecture in northern India,’ noted Cunningham. Babur, the first of the Moghuls, evidently agreed. His official diary shows that he admired and coveted this building above all others in India. In due

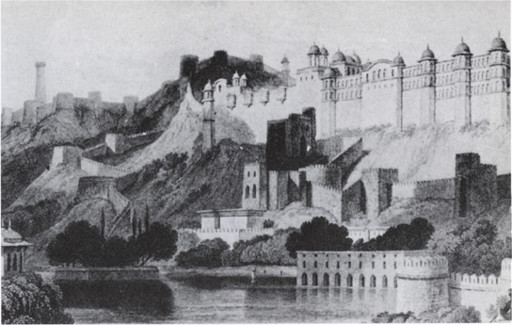

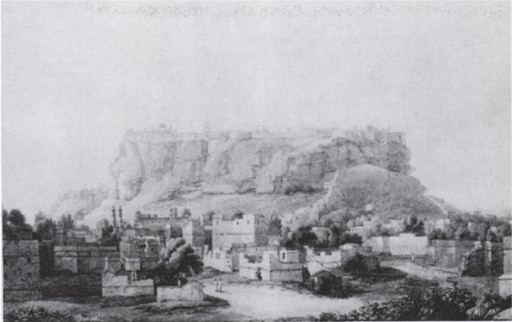

course it became the inspiration for all the palaces of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, for the Moghul forts of Delhi and Agra as well as for the Rajput forts of Orchha, Amber and Jodhpur.

“If our poets had sung them, our painters pictured them, our heroes lived in them, they would be on every man’s lips in Europe.’ Thus, with good reason, wrote E. B. Havell of the much neglected forts and palaces of the Rajputs. In his drawing of Amber Bishop Heber strove to convey the impression of ‘an enchanted castle’. Gwalior, ‘the Gibraltar of India’, furnished the inspiration for the Moghul forts of Agra and Delhi. (Watercolour by Francis Swain Ward, c. 1790.)

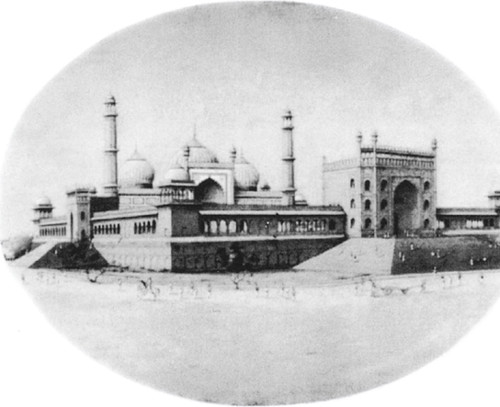

To the Islamic architecture of Delhi, the British responded with good intentions marred by questionable taste and occasional spite. The Qutb mosque was ably landscaped but its famous was crowned with a ‘silly’ pavilion that ‘looked like a parachute’. In Old Delhi Shah Jehan’s Jama Masjid was carefully repaired in the 1820s but very nearly blown up by way of reprisal after the 1857 Mutiny.

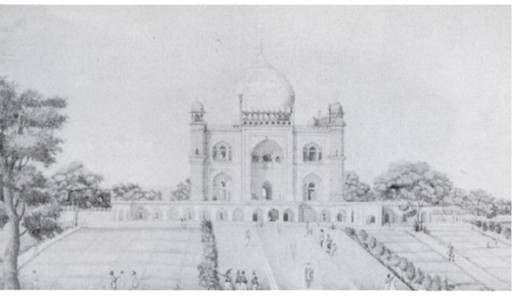

The tomb of Humayun in Delhi anticipates the Taj Mahal in Agra. In the late eighteenth century, travellers found the Taj well-endowed and much revered; but Humayun’s tomb stood neglected and anonymous amidst a wilderness of ruins. The preferential status of the Taj, ‘the gateway through which all dreams must pass’, was proudly maintained by the British, although not without reservations about whether such a masterpiece could really be Indian.