Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (17 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

The Diagonal (Pela Esqueroa) : Fluminense 1941

Brazil are almost universally recognised as having been the best side at the World Cup finals they hosted, but they did not win it. Rather they suffered a defeat in their final game so stunning that Nélson Rodrigues wrote of it as ‘our catastrophe, our Hiroshima’.

The

diagonal

imposed by Flávio Costa had undergone a minor modification, with Ademir, really an inside-forward, acting as the centre-forward, Jair, the inside-left, as the

ponta da lança

and Zizinho the deeper-lying inside-forward. The result was an enhanced fluidity and flowing triangles of passes. Brazil swept to victory in the 1949 Copa América scoring thirty-nine goals in seven games before a playoff, in which they demolished Fleitas Solich’s Paraguay 7-0.

Zizinho was injured for the start of the World Cup, but Brazil were still overwhelming favourites, and lived up to that billing in their opening match, hitting the post five times on their way to a 4-0 win over Mexico in the inaugural game at the Maracanã. Their problems began when they left Rio for their second match, against Switzerland in São Paulo. As was common at the time, Flávio Costa made several changes, bringing in three Paulista midfielders to appease local fans. Perhaps that disrupted the side, perhaps it was the 1-3-3-3

verrou

system favoured by Switzerland, but Brazil were nowhere near their usual fluency and, despite twice taking the lead, could only draw 2-2, meaning they had to beat Yugoslavia in their last group game to qualify for the final group.

Fit again, Zizinho returned in place of the robust centre-forward Baltazar, allowing Ademir to resume his role as a mobile No. 9. That would have allowed a return to the side that had won the Copa so impressively the previous year, but the draw against Switzerland seems to have caused Flávio Costa to lose faith with the

diagonal

and switch to a more orthodox W-M, perhaps reasoning that with such an adventurous and fluid central attacking three, his two half-backs, Danilo and Carlos Bauer, could both play deeper and offer additional defensive solidity.

Initially, the change worked. Yugoslavia began with ten men as Rajko Mitić received treatment after gashing his head on an exposed girder shortly before kick-off, and by the time he had made it onto the field, Ademir had given Brazil the lead. Zizinho sealed an otherwise tight game in the second half.

Yugoslavia were physically tough, technically adept opponents and, having seen them off, confidence appears to have been restored. In the opening two games of the final group, Brazil were sensational. As they hammered Sweden 7-1 and Spain 6-1, Glanville wrote of them playing ‘the football of the future… tactically unexceptional but technically superb’.

They may have been unexceptional tactically, but they were far more advanced than Uruguay, who were still playing a version of Pozzo’s

metodo

, with a ball-playing centre-half in Obdulio Varela. They had equalised late to draw 2-2 with Spain in their opening game of the final stage, and had required two goals in the final quarter hour to beat Sweden 3-2 in their second. Brazil needed only a draw in the final match to be champions, but nobody in Rio expected anything other than victory. The early editions of

O Mundo

on the day of the final even carried a team photograph of the Brazil side under the headline ‘These are the world champions’. Varela, Teixeira Heizer recounts in

The Tough Game of the World Cups

, saw the newspaper on display at the newsstand in his hotel on the morning of the final, and was so enraged that he bought every copy they had, took them back to his room, laid them out on his bathroom floor and then encouraged his team-mates to urinate on them.

Before the game, Ângelo Mendes de Moraes, the state governor, gave an address in which he hailed, ‘You Brazilians, whom I consider victors of the tournament… You players who in less than a few hours will be acclaimed champions by millions of your compatriots…. You who have no equals in the terrestrial hemisphere… You who are so superior to every other competitor…. You whom I already salute as conquerors.’

Only Flávio Costa seemed at all concerned by the possibility of defeat. ‘The Uruguayan team has always disturbed the slumbers of Brazilian footballers,’ he warned. ‘I am afraid that my players will take to the field on Sunday as though they already had the Championship shield sewn on their jerseys. It isn’t an exhibition game. It is a match like any other, only harder than the others.’

What made it particularly hard was the acuity of Juan López, the Uruguay coach. The war in Europe had meant an end to the tours, so, playing largely South American opposition the

Rioplatense

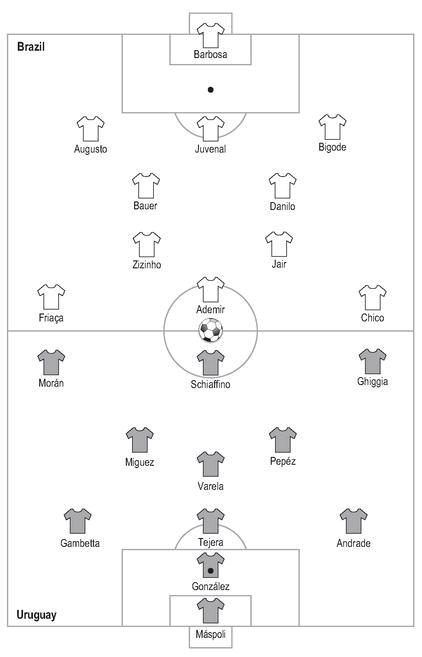

School had had little chance to witness tactical developments elsewhere. López, though, saw how Switzerland had unnerved Brazil, and drew inspiration from their system. He instructed the full-back Matias Gonzalez to stay deep, almost as a sweeper, which meant that Eusebio Tejera, the other full-back, became effectively a centre-back. The two wing-halves, Schubert Gambetta and Victor Andrade, were set to man-mark the Brazilian wingers, Chico and Albino Friaça, while Varela and the two inside-forwards played deeper than usual in a system approaching Rappan’s 1-3-3-3.

Officially there were 173,850 at the Maracanã that day; in reality there were probably over 200,000. So overcome by nerves was Julio Pérez, Uruguay’s inside-right - or right-half, in the revised formation - that he wet himself during the anthems. Gradually, though, the pressure shifted. Brazil controlled the early stages - López’s tactics perhaps subdued Brazil, but they did not neutralise them - but the opening goal would not come. Jair hit the post; Roque Máspoli, in Glanville’s words, ‘performed acrobatic prodigies in goal’; but at half-time it was still goalless. Home nerves were mounting.

Hindsight suggests the turning point came after twenty-eight minutes, when Varela punched Bigode, Brazil’s left-back. Both players agree it was barely more than a tap, but in the mythology of the game it was at that moment that the fear enveloped Bigode, at that moment that he became ‘a coward’, the taunt that would pursue him for the rest of his life.

Two minutes after half-time, a reverse ball from Ademir laid in Friaça. He held off Andrade and, with a slightly scuffed cross-shot, gave Brazil the lead. In the first half, it might have been devastating, but having held out for so long, Uruguay knew they could live with Brazil, that they would not be overwhelmed.

Whether it was a deliberate policy or not is difficult to say, but Uruguay seemed to prefer to attack down their right. That was the side that, when Brazil had played the

diagonal

, had been the more vulnerable, with Danilo the more advanced of the two half-backs. In a W-M, he couldn’t help himself but push forwards, which created a fatal space, because Bigode was now operating as an orthodox left-back rather than in the slightly advanced role he would usually have adopted. Alcide Ghiggia, Uruguay’s frail, hunched right-winger, could hardly have dreamed he would have been granted so much room.

Brazil 1 Uruguay 2, World Cup final pool, Maracanã, Rio de Janeiro, 16 July 1950

Brazil were twenty-four minutes from victory when the first blow fell. Varela, who was becoming increasingly influential, advanced, and spread the ball right to Ghiggia. He had space to accelerate, checked as Bigode moved to close him down, then surged by him, crossing low for Juan Schiaffino to sweep the ball in at the near post. ‘Silence in the Maracanã,’ said Flávio Costa, ‘which terrified our players.’ As blame was apportioned after the game, even the crowd did not escape. ‘When the players needed the Maracanã the most, the Maracanã was silent,’ the musician Chico Buarque observed. ‘You can’t entrust yourself to a football stadium.’

A draw would still have been enough for Brazil, but the momentum had swung inexorably against them. Thirteen minutes later, Ghiggia again picked up the ball on the Uruguayan right. This time Bigode was closer to him, but isolated, so Ghiggia laid it back to Perez. Nerves forgotten, he held off Jair and slipped a return ball in behind Bigode. Ghiggia ran on, and with Moacyr Barbosa, the Brazilian goalkeeper, anticipating a cross, struck a bobbling shot in at the near post. The unthinkable had happened, and Uruguay, not Brazil, were world champions.

Brazil, only founded as a nation in 1889, has never been in a war. When Rodrigues spoke of the 1950 World Cup final as his country’s ‘Hiroshima’, he meant it was the greatest single catastrophe to have befallen Brazil. Paulo Perdigão expresses the same point less outrageously in

Anatomy of a Defeat

, his remarkable meditation on the final, in which he reprints the entire radio commentary of the match, using it as the basis for his analysis of the game almost as though he were delivering exegesis upon a biblical text. ‘Of all the historical examples of national crises,’ he wrote, ‘the World Cup of 1950 is the most beautiful and most glorified. It is a Waterloo of the tropics and its history our

Götterdämmerung

. The defeat transformed a normal fact into an exceptional narrative: it is a fabulous myth that has been preserved and even grown in the public imagination.’

Bigode, Barbosa and Juvenal - probably not by coincidence Brazil’s three black players - were held responsible. In 1963, Barbosa, in an effort to exorcise his demons, even invited friends to a barbecue at which he ceremonially burned the Maracanã goalposts, but he could not escape the opprobrium. The story is told of how, twenty years after the final, he was in a shop when a woman pointed at him. ‘Look at him,’ she said to her young son. ‘He’s the man who made all of Brazil cry.’

‘In Brazil,’ he said shortly before his death in 2000, ‘the maximum sentence is thirty years, but I have served fifty.’ Yes, it was a mistake, but if a reason is to be found for the defeat, Zizinho insists, it is the use of the W-M. ‘The last four games of the World Cup were the first time in my life I played W-M,’ he explained in an interview with Bellos. ‘Spain played W-M, Sweden played W-M, Yugoslavia played W-M. The three that played W-M we beat. But Uruguay didn’t play W-M. Uruguay played with one deep back and the other in front.’ They played, in other words, a system whose defensive base was the same as that used by Brazil to win the Copa América in 1919.

Just as England reacts to any set-back by lamenting technical inadequacy, so Brazil blames defensive frailties. Perdigão’s reference to

Götterdämmerung

, of course, echoes the

Mirror

’s ‘Twilight of the Gods’ headline after England’s 6-3 defeat to Hungary, and that is not coincidence. The plaintiveness comes from the same source - a railing against habitual failings, an angry realisation that the traditional way of playing is not innately superior. The irony is that Brazil’s traditions and England’s could hardly be more different. There is no right way of playing; at some point every football culture doubts its own strengths and looks wistfully to the greener grass abroad.

No matter that twenty-two goals had been scored in six games; what was important was those two that had been conceded at the last. Clearly, Brazil’s pundits decided, the defence needed bolstering. By the time of the 1954 World Cup, the attack-minded Flávio Costa had been supplanted by the more cautious Zezé Moreira. It was, a French journalist said, like replacing an Argentine dancer with an English clergyman.