Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (14 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

And yet the

Aranycsapat

remained forever unfulfilled. After thirty-six games undefeated, Hungary threw away a two-goal lead to lose 3-2 to West Germany in the 1954 World Cup final, undone, in the end, by ill luck, a muddy pitch that hampered their passing game, a touch of complacency and the German manager Sepp Herberger’s simple ploy of sitting Horst Eckel man-to-man on Hidegkuti. A system thought up to free the centre-forward from the clutches of a marker fell down when the marker was moved closer to him.

Perhaps, though, they paid as well for a defensive frailty. Even allowing for the attacking standards of the time, the Hungarian defence was porous. The three they conceded to West Germany meant they had let in ten in the tournament, while in 1953 they leaked eleven goals in a six-game run that culminated in the 6-3 win at Wembley. Just about everybody agreed that the three flattered England, an observation taken at the time to emphasise Hungary’s superiority, but it could just as well be interpreted as a criticism of their laxity.

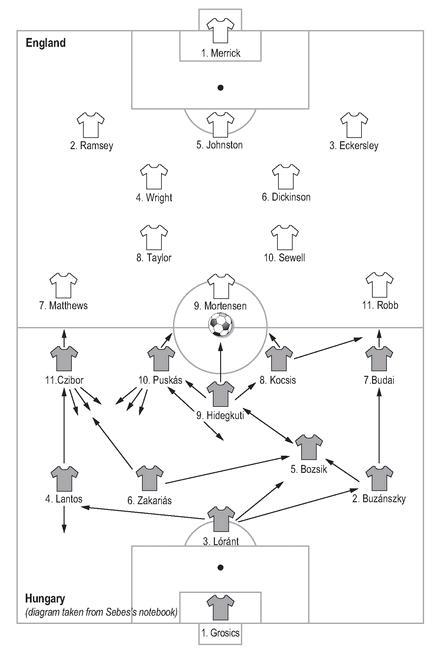

England 3 Hungary 6, friendly, Wembley, London, 25 November 1953

The problem with three at the back is that the defence operates on a pivot, with the left-back tucking in alongside the centre-back if attacks come down the right and vice versa, rendering it vulnerable to being ‘turned’ by a smart cross-field ball that, at the very least, gave the winger on the opposite flank acceleration room. Zakariás, still notionally a midfielder, did not play deep enough to provide the extra cover that would have allowed a full-back to remain tighter to the winger he was supposed to be marking.

Whatever the cause of the defeat in Berne, the response in Hungary was one of fury. When they had returned after beating England at Wembley, the

Aranycsapat

had been greeted by adoring crowds; after losing the World Cup final they had to be diverted to the northern town of Tata to avoid street demonstrations. Puskás was barracked at league games, Sebes’s son was beaten up at school, and the goalkeeper, Gyula Grosics, was arrested. Through 1955, the management team Sebes had constructed was dismantled and, following a 4-3 defeat to Belgium the following year, he was replaced by a five-man committee headed by Bukovi. Amid the chaos of the Uprising and the subsequent defections of several players, though, his task was an impossible one. Sebes, meanwhile, lingered a while in sports administration as the deputy head of the National Physical Education and Sports Committee, before taking on a string of coaching positions, eventually retiring in 1970. ‘When I was a kid, Sebes lived in the same area of Budapest as me,’ remembers the great Ferencváros forward of the seventies, Tibor Nyilasi. ‘He would come down to the square where I played football with my friends, and take us up to his flat, give us sandwiches, and show us Super-8 films of the 6- 3 and 7-1 games. It was he who recommended me to Ferencváros. He was like a grandfather. He only lived for football.’

While it was the national team’s performances that attracted the most attention at the time, it was probably Sebes’s compatriot Béla Guttmann who had a more lasting influence on the game. To claim that he invented Brazilian football is stretching things, but that didn’t stop him trying. What is beyond dispute is that he represented the final flowering of the great era of central European football; he was the last of the coffee-house coaches, perhaps even the last defender of football’s innocence.

The two great Hungarian managers of the era could hardly have been more different. Where Sebes was a committed socialist, happy to spout the Party line and play the diplomatic game, Guttmann was a quick-tempered individualist, a man chewed up by circumstance and distrustful and dismissive of authority as a consequence. The end of his international playing career after three full caps was typical. Selected for the 1924 Olympics in Paris, Guttmann was appalled by Hungary’s inadequate preparations. There were more officials than players in the squad, and the party accordingly was based in a hotel near Montmartre: ideal for the officials’ late-night socialising, less good for players who needed to sleep. In protest Guttmann led a number of his team-mates on a rat-catching expedition through the hotel, and then tied their prey by the tails to the handles of the officials’ room-doors. He never played for his country again. Guttmann lived life like the world’s rejected guest, always on the lookout for a slight, always ready to flounce, irritating and irritated in equal measure.

Born in Budapest in 1899 to a family of dance instructors, Guttmann qualified as a teacher of classical dance when he was sixteen. It was football that really fascinated him, though, and, playing as an old-school attacking centre-half - contemporary accounts almost invariably describe him as ‘graceful’ - he impressed enough with the first-division side Torekves to earn a move in 1920 to MTK, a club seen as representing Budapest’s Jewish middle-class and a club still playing in the style Jimmy Hogan had introduced.

At first, Guttmann was cover for Ferenc Nyúl, but he soon left for the Romanian side Hagibor Cluj, leaving the younger man to function as MTK’s fulcrum as they won the championship in 1921, the sixth in a run of ten straight titles interrupted only by a three-year hiatus for the war. The following season, though, Nyúl returned and, ousted from the team, Guttmann did what he would go on to do throughout his career: he walked, following the route of many Jews fearing persecution from the Miklós Horthy regime and heading for Vienna. It was the first of twenty-three moves Guttmann would make across national borders.

Anti-Semitism was not exactly unknown in Vienna, but it was there, amid the football intellectuals of the coffee houses, that Guttmann seems to have felt most at home. ‘Later,’ the journalist Hardy Grüne wrote in the catalogue of an auction of Guttmann memorabilia held in the German town of Kassel in 2001, ‘he would often sit in São Paulo, New York or Lisbon and dream of enjoying a

Melange

in a Viennese café and chatting to good friends about football.’ When, aged seventy-five, Guttmann finally gave up his wandering, it was to Vienna he returned, living in an apartment near the opera house on Walfischgasse.

He joined Hakoah, the great Jewish club of Vienna, late in 1921, and supplemented the small income they were able to provide by setting up a dancing academy. They too practised the Scottish passing game, as preached by their coach Billy Hunter, who had played for Bolton Wanderers - alongside Jimmy Hogan - and Millwall. Although central Europe had never embraced the brute physicality of the English approach, Hunter’s ideas were to have a lasting impact.

Hakoah turned professional in 1925 and, with Guttmann at centre-half, won the inaugural professional Austrian championship the following year. Just as important to the club were the money-making tours they undertook to promote muscular Judaism in general and Zionism in particular. In 1926, billed as ‘the Unbeatable Jews’ (although they lost two of their thirteen games), Hakoah toured the east coast of the USA. In terms of money and profile, the tour was a tremendous success, and in that lay Hakoah’s downfall. The US clubs were richer than Hakoah and, after agreeing a much-improved contract, Guttmann joined the New York Giants. By the end of the year, half the squad was based in the city.

From a football point of view, Guttmann prospered, winning the US Cup in 1929, but, having bought into a speakeasy, he was ruined as the economy disintegrated after the Wall Street Crash. ‘I poked holes in the eyes of Abraham Lincoln on my last five-dollar bill,’ he said. ‘I thought then it wouldn’t be able to find its way to the door.’ Always a man with an eye for the finer things in life - at Hakoah he insisted his shirts be made of silk - he seems also to have vowed then that he would never be poor again. He stayed with the Giants until the US league collapsed in 1932, returning to Hakoah to begin a coaching career that would last for forty-one years.

He stayed in Vienna for two seasons and then, on the recommendation of Hugo Meisl, moved on to the Dutch club SC Enschede. He initially signed a three-month contract but, when they came to negotiate a new deal, he insisted upon a huge bonus should Enschede win the league. As the club was struggling to avoid relegation out of the Eastern Division, the directors readily agreed. Their form promptly revived and, after they had narrowly missed out on the national championship, their chairman admitted that towards the end of the season he had gone to games praying his side would lose: Guttmann’s bonus would have bankrupted them.

He would have had little compunction about accepting it. Some managers are empire-builders, committed to laying structures that will bring their clubs success long after they have gone; Guttmann was a gun for hire. He bargained hard and brooked no interference. ‘The third season,’ he would say later in his career, ‘is fatal.’ He rarely lasted that long. After two years in Holland he returned to Hakoah, fleeing to Hungary after the Anschluss.

What happened next is unclear. Whenever he was asked how he survived the war, Guttmann would always reply, ‘God helped me.’ His elder brother died in a concentration camp, and it seems probable that contacts from Hakoah helped him escape to Switzerland, where he was interned. It was certainly there that Guttmann met his wife, but he refused always to speak of his wartime experiences, and his autobiography, published in 1964, contains a single paragraph on the subject: ‘In the last fifteen years countless books have been written about the destructive years of struggle for life and death. It would thus be superfluous to trouble our readers with such details.’

By 1945, he was back in Hungary with Vasas, and the following spring he moved on to Romania with Ciocanul, where he insisted on being paid in edible goods so as to circumvent the food shortages and inflation afflicting most of Europe at the time. His departure was characteristic. When a director sought to interfere with team selection, Guttmann apparently turned to him, said, ‘OK, you run the club; you seem to have the basics,’ and left.

The following season he won the Hungarian title with Újpest, and then it was on to Kispest, where he replaced Puskás’ father as coach. A row with Puskás, no shrinking violet himself, was inevitable, and it came in a 4-0 defeat to Győr. Guttmann, who was insistent that football should be played the ‘right way’, had spent the first half trying to calm the aggressive approach of the full-back Mihály Patyi. Furious with him, Guttmann instructed Patyi not to go out for the second half, even though that would leave Kispest down to ten men. Puskás told the defender to stay on. Patyi vacillated, and eventually ignored his manager, at which Guttmann retired to the stands for the second half, most of which he spent reading a racing paper, then took a tram home and never returned.

On he wandered: to Triestina and Padova in Italy, to Boca Juniors and Quilmes in Argentina, to Apoel Nicosia in Cyprus, and then, midway through the 1953-54 season, to AC Milan. He lifted them to third in that first season, and had them top of the table when he was dismissed nineteen games into 1954-55 following a series of disputes with the board. ‘I have been sacked,’ he told a stunned press conference convened to announce his departure, ‘even though I am neither a criminal nor a homosexual. Goodbye.’ From then on he insisted on a clause in his contracts stipulating he couldn’t be dismissed while his team were top of the league.

He moved to Vicenza, but left twenty-eight games into the season, and was without a job for most of 1956, before the Budapest Uprising provided him with an opportunity. When Honvéd (as Kispest had become known after being taken over by the army), seeking to keep their players away from the fighting, accepted a long-standing invitation to tour Brazil and Venezuela, Guttmann, by this time reconciled with Puskás, was placed in charge. Finding himself in demand in South America, he decided to stay on, accepting a contract with São Paulo. And so it was, Guttmann claimed, that the Hungarian 4-2-4 was exported to Brazil, although the truth is rather more complex.

Guttmann led São Paulo to a Paulista title in 1957, but was quickly off, returning to Europe with Porto. A coach, he said, is like a lion tamer. ‘He dominates the animals, in whose cage he performs his show, as long as he deals with them with self-confidence and without fear. But the moment he becomes unsure of his hypnotic energy, and the first hint of fear appears in his eyes, he is lost.’ Guttmann never stayed long enough for that hint of fear to materialise.