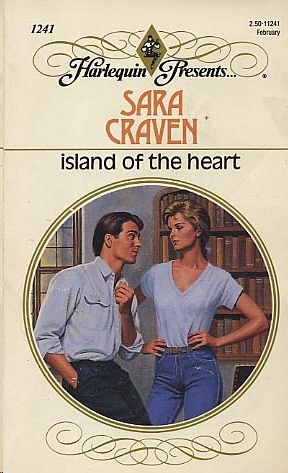

Island of the Heart

ISLAND OF THE

HEART

Sara Craven

It was a marvelous opportunity

And Sandie grabbed it. Only afterward did she realize she'd been a

little naive.

When noted pianist and composer Crispin Sinclair offered her free

tuition at his Irish home, she had no idea how closely she resembled

the wife he hadn't got around to divorcing. And she'd viewed

Crispin only as a musician, not a man.

So it was as well the enigmatic Flynn Fillane was around to remove

he from the consequences of her folly. Sandie hoped, though, it

wouldn't prove to be out of the frying pan, into the fire!

FOR JOHN AND EVANGELINE ROCHE AND ALL THE FRIENDS I FOUND

AT THE ROCK GLEN, CLIFDEN.

THE last chords sang their way triumphantly into the echoing

silence, and Sandie Beaumont lifted her hands from the keyboard as

the applause began.

The adrenalin which had carried her through the performance was

already starting to subside as she rose and bowed to the clapping

audience. She kept her hands hidden in the folds of her violet taffeta

skirt to disguise the fact that they were shaking.

Listening intently, she tried to judge the audience reaction to her

playing. It was enthusiastic, but was it the kind of acclaim accorded

to a winner? Sandie wasn't sure.

She deliberately avoided even a glance towards the row of judges

seated behind their table at the front of the auditorium. She would

know their verdict soon enough.

"It's not the end of the world.' That was what one of her fellow

contestants had said as he'd left the waiting-room backstage where

they were all assembled an hour earlier.

And in a way it wasn't. It was a piano contest in a newly established

music festival, that was all. A first rung on the ladder to such glories

as the Leeds Piano Competition.

But for me, Sandie thought, as she bowed again, and made her way

with forced composure off the platform, for me, it could easily be

the end of everything.

There was a long mirror at the end of the corridor leading back to

the dressing-rooms. She'd been too nervous to use it on her way to

the platform, but she paused now to glance at herself, swiftly and

clinically. Too pale, she thought. She should have used more

blusher. In the dim light of the passage, with her silvery blonde hair

hanging straight and shining below her shoulders, she looked almost

ghostly.

But the dress was wonderful. It had been an extravagance, but it was

worth it, accentuating, as it did, the colour of her own violet eyes. It

had made her feel good, given her the confidence to believe that

everything was going to be all right. As if a career in music, as she'd

always dreamed, was actually within reach.

Her hands balled into fists of tension, and she swallowed as she

turned away. Well, she would soon know. She'd been the last

competitor.

Back in the big room, where the others waited, no one was saying

much. They were all on edge now, anticipating the call which would

take them back on stage for the adjudication. Most of them seemed

to know each other already—to be able to judge the standard they

were up against. She, Sandie, was the outsider, the unknown

quantity. The local girl taking her first step towards national fame—

or instant obscurity.

Her parents had been quite adamant.

'My dear, you don't realise the kind of odds you're up against,' her

father had said. 'Yes, you've got talent, I don't doubt, but that's not

enough to make you a star at international level. You may be Mrs

Darnley's prize pupil, but what does that really mean?'

'I don't know,' Sandie had returned desperately. 'But you've got to let

me find out.'

Her parents exchanged uneasy glances. She knew what they were

thinking. They were remembering Sandie's grandmother, the

Alexandra for whom she had been named, whose considerable

musical talent had never taken her further than the orchestras of

second-rate touring variety shows and seaside concert parties. For

years she'd soldiered on, declaring her big break would come—only

it never had, and the realisation that it never would had led to

increasing bouts of depression until her death, still in early middle

age.

They don't want that to happen to me, Sandie thought. They don't

want me to break my heart, searching for some big time which may

never come..

Aloud, she said, 'You've got to let me have my chance.'

'Then we will.' Her father knocked out his pipe in the ashtray. 'Mrs

Darnley's entered you for the festival. If you can win it, you shall

have your chance— music college and the rest—whatever it takes.

If you don't win, then you give up all thoughts of a career as a

pianist. Is it agreed?'

'All or nothing—just like that?' Sandie stared at them pleadingly.

'Mum, I...'

'Your father and I are in total agreement.' Mrs Beaumont spoke

more gently than her husband. 'It's for your own sake, darling. After

all, Sandie, you're nineteen now. Most professional musicians

started training years before you did.'

'That's hardly my fault.' Sandie remembered the uphill struggle to

persuade her parents to allow her to have piano lessons at all.

'No,' her mother agreed. 'But you can't blame us for being cautious.

It's time you put all this nonsense behind you, and trained for

something—settled down. If it has to be music, you could always

teach. You don't have to go on being a legal secretary, if you really

hate it so much.' She gave Sandie an anxious smile. 'And you can

always play the piano for your own amusement.'

Sandie had winced.

Mrs Darnley had been sympathetic, but had refused to take up the

cudgels on Sandie's behalf.

'Your parents are doing what they feel is right,' she said. 'I can't

argue about their natural concern for you. And they could have a

point.'

Sandie stared at her. 'But I thought you believed in me,' she said,

biting her lip. 'Don't you think I can make it?'

Mrs Darnley sighed. 'Sandie, you're the best pupil I've ever had, but

that's all I can say. You've outgrown me, my dear. From now on,

you need specialist coaching that I'm not qualified to give you—

master classes. It all costs money, and if your parents aren't prepared

to make a contribution...' She left it at that.

Now, weeks later, Sandie looked under her lashes at her fellow

competitors and wondered. They all wanted to win—that went

without saying. But did any of them have the compulsive, driving

need to come first that she possessed?

She thought, My whole future depends on this.

It seemed an eternity before the recall to the platform came. They

filed on and stood trying to look nonchalant and modest at the same

time. Sandie's legs were shaking, and her mouth felt dry. She

wanted it over with. She wanted to

know.

The judges moved on to the platform, and she studied them

unobtrusively, trying to read their faces, to see if they looked longer

in one direction than another.

The tall man standing at the end caught her eye and smiled, and she

felt herself blush.

She knew who he was, of course. They were all musical celebrities,

but he was the star. Crispin Sinclair, the youngest of the four, had

been a young virtuoso pianist himself some years before, spoken of

as a prodigy. He was one of Sandie's heroes, and she had several of

his recordings. But in recent years, he'd turned from the concert

platform to composition. He'd written a modern opera based on Sean

O'Casey's

Juno and the Paycock,

which had been received with

acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as a host of shorter

works, many of them commissioned. One of them was to be

performed at the end of the festival, and Crispin Sinclair himself

was going to conduct.

It was also rumoured that, under different names, he'd written music

for various well-known pop groups.

But he'd had a head start in the musical world, Sandie thought,

staring embarrassedly at the floor. His mother was Magda Sinclair,

the world-famous mezzo-soprano and opera star, and his sister

Jessica was already a noted cellist. No one in his family would have

ever jibbed at his choice of occupation. He would have been

encouraged and nursed along since babyhood, and the first signs of

precocious talent.

Whereas I didn't even have a piano until I was ' thirteen, Sandie

thought, with a sigh.

All the same, she couldn't help wondering if the smile he'd sent her

held any significance.

She tried to concentrate on what the chairman of the judging panel

was saying. There were the usual platitudes about the excellent

organisation, and thanks to the patrons and sponsors before he

turned to 'the wealth of talent here tonight,' 'the distinctive

performances', 'the difficulty of reaching a decision, although the

panel had been unanimous...'

Oh, get on with it, Sandie prayed silently, her in- sides knotting with

tension.

'The results will be in reverse order,' he was saying, and paused in

anticipation of the laugh. 'Just like Miss World.' He consulted the

paper in his hand. 'In third place—Jennifer Greenslade.'

Applause broke out. Sandie watched the other girl, no more than

fourteen, go up to get her prize, her face flushed with pleasure.

'And in second place -' the chairman paused theatrically, making the

most of it, 'Alexandra Beaumont.'

More applause. Sandie heard it from a distance— from some limbo

of pain and disappointment.

She had to force herself to move, terrified that her legs would betray

her, and that she'd collapse there and then in front of them all. But of

course she didn't. She took her prize envelope, shook hands, and

managed to smile and say something polite as she was

congratulated.

She didn't see or hear who came first. She went back to her place,

alone, lost in a little nightmare world of despair and failure.

She couldn't look at the audience, at the place where she knew her

parents were sitting. They'd be disappointed for her, she knew, but

relieved as well. She'd done well, and justified Mrs Darnley's good

opinion, but not quite well enough, so now the whole nonsensical

idea could be abandoned, and life return to normal.

Normality, she thought bleakly. A teachers' training college, or a

solicitors' office. That was the choice now.

She was thankful when the ceremony was over and she could escape

to the privacy of the small dressing- room she'd been allocated. She

pulled off that mockery of a taffeta dress, slinging it carelessly on to

a chair in the corner before struggling back into the sweatshirt and

jeans she'd worn earlier.

The tap on the door startled her. She tugged the sweatshirt down

into place, scooping her long hair free of its collar. She supposed it

would be her father and mother, knocking tactfully in case she was

upset. But she was too aching, too stunned to cry. Tears would come

later, she thought.

She called, 'Yes?' and the door opened, and Crispin Sinclair walked

in.

'So this is the right room.' When he smiled, his teeth were very

white. 'I came to offer my condolences. It was a very near thing,

actually.'

'So near and yet so far,' Sandie said. She tried to speak lightly, but

her voice broke a little in the middle.