Jane Austen For Dummies (34 page)

Read Jane Austen For Dummies Online

Authors: Joan Elizabeth Klingel Ray

Living Life in Jane's World

In this part . . .

A

lthough Austen's heroines may appear to have lives of leisure, the reality lurking over all their heads (except for Emma Woodhouse's, because she's unique in being rich) was pretty grim. Part III explains the limited social, legal, and financial opportunities and choices for ladies. And while men enjoyed all the rights not available to women, a gentleman's family had specific expectations for its sons, especially its elder son. Along with a survey of life for the gentry, this Part also discusses the manners and morals, both religious and secular, of Austen's times.

Looking at Ladies' Limited Rights and Roles

In This Chapter

Examining how to live like a lady

Examining how to live like a lady

Understanding how to please men

Understanding how to please men

Becoming an accomplished woman

Becoming an accomplished woman

Advocating the feminist outlook

Advocating the feminist outlook

Being single and becoming a governess

Being single and becoming a governess

L

adies' lives in Austen's novels appear to be charmed. After all, after courtship and marriage are achieved, ladies in the novels don't do very much.

Mansfield Park

's Lady Bertram, the wife of a baronet, dozes on the sofa. Although widowed, Mrs. Dashwood, the heroines' mother in

Sense and Sensibility,

has two female and one male servant, even in her difficult financial circumstances. And

Pride and Prejudice

's Mrs. Bennet, with a housekeeper, a cook, and assorted maids to take care of the daily routine at Longbourn, makes work for herself in seeking husbands for her five daughters by attending balls and hosting dinner parties. But for all the elegance and ease of their lives, these ladies faced a common dilemma: In marrying they surrendered all of their legal and financial rights to their husbands â not that they missed them, because prior to their marriage, all their rights were controlled by their fathers. So the rights were never theirs to begin with.

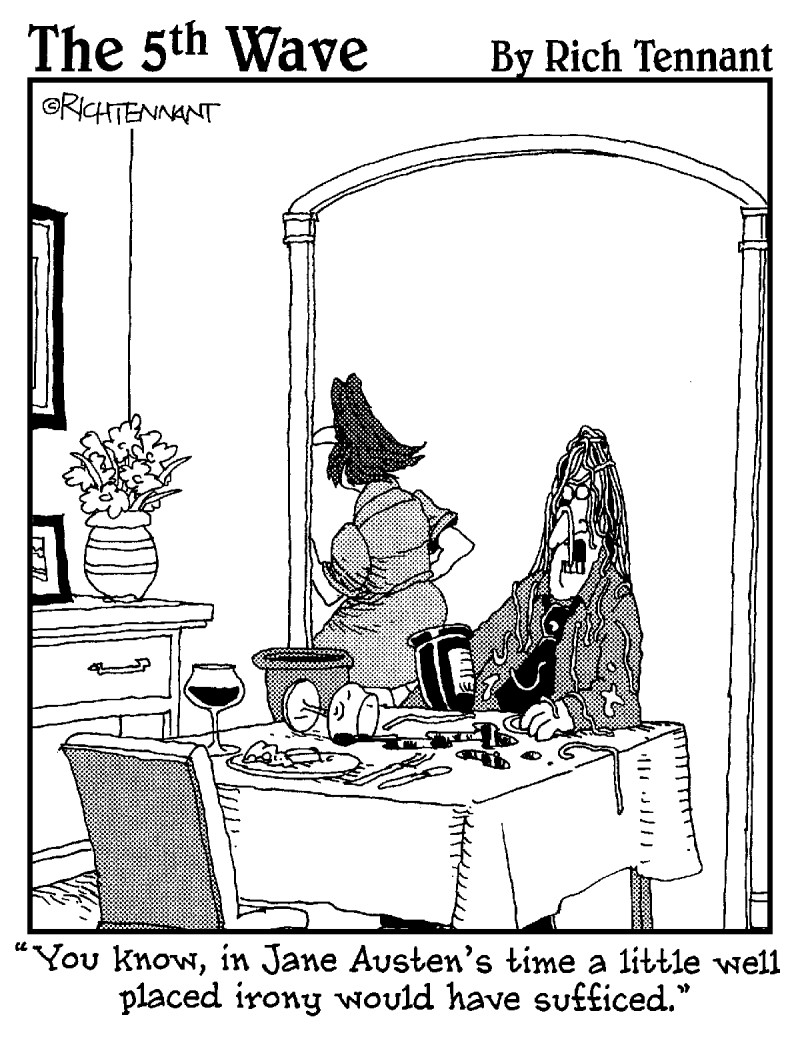

While Austen's world was a man's world, she lived at a time when ladies' rights were beginning to be discussed openly and somewhat loudly. But with her usual tact and subtlety, Austen makes herself heard in a quieter, yet steadfast way.

Because a female had no legal or economic rights in Austen's day, she had to be careful when choosing a husband. For in surrendering her money and her rights to her husband, she wanted to be as sure as she could that he would treat her with respect, fairness, and love. No law required him to do so. In fact, the law gave him the right not to do so. (For details on marriage, see Chapter 7.) Ladies lived with a set of customs that denied them a great deal. Consequently, women were dependent on men.

Ladies' legal rights were minimal. Under the law a lady could not do things that women today take for granted. She could not

Vote

Vote

Attend a university

Attend a university

Enter a profession

Enter a profession

Control her money and property (including her children and her clothes!)

Control her money and property (including her children and her clothes!)

Rarely did a married lady hold property in her own name.

Sense and Sensibility

's widowed Mrs. Ferrars is unique in Austen's canon because she controls the family's substantial money and property, and with the stroke of a quill she disinherits her elder son and transfers all of his inheritance to her younger son. The late Mr. Ferrars was highly unusual in leaving his estate to his wife. Likewise, owning The Rosings estate, the widowed Lady Catherine de Bourgh of

Pride and Prejudice

is another unusual female property owner. In her case, her late husband's family didn't think it “necessary” to entail the property on males. (Entails restrict an inheritance line. For more on entails, see Chapter 10.) More frequently, a lady's one option for securing her own property was to place it in a trust. Her husband had

â¢

Control of their children:

Her husband controlled the kids and could, if he wanted, take them away from their mother.

â¢

Control over their sex life:

Her husband could demand sex â and even rape her or commit adultery.

â¢

The right to hit her:

Even if the husband locked her up in the attic, beat her, denied her access to her children, and emotionally abused her, she was his property, and so he could do as he liked. (For information on divorce, see Chapter 7.)

Now that you've read the downside of being a woman in Austen's time, don't think that she lived in a nation of wife-beaters; a majority of marriages were happy or at least satisfactory, and most wives weren't beaten!

A father owned his daughter(s), literally. He was in charge of housing, clothing, and feeding her. As a gentleman, he was responsible for seeing to it that she had the dowry money â money that her mother or even her father brought to the table prior to their marriage â to secure a good husband. But was he required by law to supply the dowry? No.

A girl of the genteel class hoped and trusted that her parents' marriage settlement â money that her parents brought to the table back when their family's lawyers negotiated the finances of their marriage â included dowry money for her future marriage. Her father's wise use of this money would leave his children, younger sons, and widow comfortably provided for financially. (For more on marriage articles or settlement, see Chapter 7.) A father who had failed to use the marriage settlement carefully was pretty much considered a failure as a father.

For a young lady of the gentry, her dowry was key to marrying well. With a small dowry or with no dowry at all, the chances of marriage decreased dramatically, even hopelessly.

So belonging to daddy may have been comforting for a time. But if papa failed to think ahead financially, his daughters and even his younger sons faced financial problems in the future. And the situation was worse for the daughters. For the sons could at least pursue the gentlemanly occupations discussed in Chapter 10, and thus earn their income.

The following list describes the many father characters in Austen's fiction who've essentially failed their daughters financially:

Mr. Watson:

Mr. Watson:

The Watsons

features Austen's most pathetic father â the frail, helpless, elderly, and

poor

Mr. Watson. He's a retired clergyman and a really lovely man, but the clergy had no pension fund to assist the clergyman's survivors at this time. So in terms of helping his daughters to marry well, he's a failure. He has unmarried daughters who appear to be with small, if any, dowries. As a result, sisterly disharmony reigns in the Watson household.

Mr. Bennet:

Mr. Bennet:

Pride and Prejudice

's five unmarried Bennet sisters have £1,000 apiece from their parents' marriage settlement to use as their dowries. While this is a great dowry for each Bennet daughter compared to what the Watson sisters have, Mr. Bennet wishes too late that “instead of spending his whole income, he had laid by an annual sum for the better provision of his children” (PP 3:8). When Mr. Collins taunts Elizabeth by telling her that her chances of marrying are little because “âher portion [dowry, or portion of her parents' marriage settlement] is unhappily so small,” he is absolutely correct (PP 1:19). If the Bennet sisters don't marry, they would have an annual income of between 4 and 5 percent on their collective £5,000 or between £200 and £250 annually to live on (roughly $24,000 in 2004); the Bennets' current family income, with Mr. Bennet alive and the Longbourn farm, is £2,000â an income they'll lose to Mr. Collins after Mr. Bennet's death because the Longbourn property is entailed on male heirs.

Mr. Dashwood:

Mr. Dashwood:

After

Sense and Sensibility

's Mr. Dashwood dies, the four females of his household live on £500 a year (SS 1:2). Thus, they have to cut back a lot on everything they were used to enjoying. Mr. Dashwood was so confident that his uncle would leave the family's estate to him, his wife, and daughters, that he made little alternative provision for them. Only because their uncle left each girl £1,000 do they have dowries equivalent to the Bennet sisters' dowries â which as Mr. Collins observed, was “small.”

Sir Walter Elliot:

Sir Walter Elliot:

Persuasion

's baronet has been such a spendthrift that when his daughter Anne marries, he “could give [her] at present but a small part of the share of ten thousand pounds which must be hers hereafter” (P 2:12).

Austen also provides a few fathers who provide well for their daughters:

The Rev. Mr. Morland:

The Rev. Mr. Morland:

The father of

Northanger Abbey

's heroine is a sensible father. His daughter, Catherine, has a dowry of £3,000 to bring to her marriage with Henry Tilney.

Mr. Woodhouse:

Mr. Woodhouse:

In

Emma,

Emma's parents' finances were such that she is worth £30,000, making her quite rich!

Sir Thomas Bertram:

Sir Thomas Bertram:

Although the head of

Mansfield Park

's Bertram family let his elder son get away with wasting money, Sir Thomas pays an extensive visit to his plantation in Antigua, the West Indies, to recoup his finances.

Mr. Musgrove:

Mr. Musgrove:

If

Persuasion

's Sir Walter is the financially careless father, Mr. Musgrove, a hearty, prosperous gentleman-farmer, faces no financial problem in marrying off two daughters at once.