John Quincy Adams (25 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

Out at sea, America's little navyâtwelve fast and highly maneuverable shipsâhad better results. The forty-four-gun frigate

Constitution

demolished Britain's thirty-eight-gun

Guerrière

off the coast of Nova Scotia in only thirty minutes, killing seventy-nine British sailors and losing only

fourteen of her own. Other American ships humiliated Britain's navy off the coasts of Virginia and Brazil. Captain Stephen Decatur's

United States

captured a thirty-eight-gun British frigate near the Madeira Islands off the African coast and brought her all the way back across the Atlantic Ocean to New London, Connecticut, as a prize of war. Complementing the tiny American navy were five hundred privateers, which captured about 1,300 British cargo ships valued at $39 million and forced the British navy to plug America's outlets to the sea with an impenetrable blockade of gunboats along the Atlantic coast and the mouth of the Mississippi River.

Constitution

demolished Britain's thirty-eight-gun

Guerrière

off the coast of Nova Scotia in only thirty minutes, killing seventy-nine British sailors and losing only

fourteen of her own. Other American ships humiliated Britain's navy off the coasts of Virginia and Brazil. Captain Stephen Decatur's

United States

captured a thirty-eight-gun British frigate near the Madeira Islands off the African coast and brought her all the way back across the Atlantic Ocean to New London, Connecticut, as a prize of war. Complementing the tiny American navy were five hundred privateers, which captured about 1,300 British cargo ships valued at $39 million and forced the British navy to plug America's outlets to the sea with an impenetrable blockade of gunboats along the Atlantic coast and the mouth of the Mississippi River.

Although the navy's exploits lifted American morale, they did little to turn the tide of war, and less than three months after the American army had fired its first shots, Secretary of State Monroe instructed the American minister in London to approach the British foreign office with an offer of peace. The proposal simply repeated America's prewar demands, however, and Britain rejected it.

As word of American defeats reached St. Petersburg, John Quincy Adams's friend the czar offered to mediate the Anglo-American dispute. John Quincy's influence had left the czar an admirer of all things American, although he remained allied to Britain in the war against France. With the U.S. Navy bottled up and British forces in Canada poised to invade, President Madison jumped at the czar's offer, hailing John Quincy as a master diplomat. The President's peace envoys had no sooner sailed off to St. Petersburg, however, when a British frigate renewed the fighting with another attack on the ill-fated USS

Chesapeake,

killing 146 American seamen before capturing the ship and sailing it to Nova Scotia as a prize. With the British sensing victory in the war near at hand, London abruptly rejected the czar's offer to mediate, leaving America's peace envoys bobbing across the Atlantic on a useless voyage.

Chesapeake,

killing 146 American seamen before capturing the ship and sailing it to Nova Scotia as a prize. With the British sensing victory in the war near at hand, London abruptly rejected the czar's offer to mediate, leaving America's peace envoys bobbing across the Atlantic on a useless voyage.

The humiliation of the

Chesapeake

set Americans aroar with anger at what they now called “Madison's War.” New Englanders demanded Madison's resignation, and settlers in the West took matters into their own hands, pouring into army camps to avenge defeats by the British. General

Henry Dearborn, who had failed in his first invasion of Canada at Niagara, now had a corps of ardent patriots to replace the recalcitrant New York militiamen who had refused to fight outside state borders. They sailed across Lake Ontario and swept into York (now Toronto), the capital of Upper Canada (now Ontario), burning the city's public buildings, including the Assembly houses and governor's mansion.

Chesapeake

set Americans aroar with anger at what they now called “Madison's War.” New Englanders demanded Madison's resignation, and settlers in the West took matters into their own hands, pouring into army camps to avenge defeats by the British. General

Henry Dearborn, who had failed in his first invasion of Canada at Niagara, now had a corps of ardent patriots to replace the recalcitrant New York militiamen who had refused to fight outside state borders. They sailed across Lake Ontario and swept into York (now Toronto), the capital of Upper Canada (now Ontario), burning the city's public buildings, including the Assembly houses and governor's mansion.

After the raid, the Americans trekked westward around Lake Ontario to Niagara and joined 2,500 troops under Colonel Winfield Scott in capturing Fort Niagara, Fort Erie, and Buffalo's Black Rock Navy Yard, where they freed five American warships. To these ships, Secretary of the Navy William Jones added six new warships, giving Captain Oliver Hazard Perry a lake fleet of ten shipsâfour more than the British squadron. On September 10, 1813, Perry engaged the British at Put-in-Bay for three hours. The battle left Perry's ship in splinters and killed or wounded 80 percent of his men, but inflicted even more damage on the enemy. The British retreated, ceding control of Lake Erie to the Americans. Perry emerged from the wreckage and sent his famous message: “We have met the enemy, and they are ours.”

12

12

Perry's victory allowed General William Henry Harrison's troops in the west to rout a combined force of British and Indian warriors on the banks of the Thames River, killing Shawnee chief Tecumseh and giving Harrison control of the Illinois, Indiana, and other northwestern territories. When news of the American victories reached London, the British prime minister reversed his previous stance and sent Secretary of State Monroe an offer to begin direct negotiations for peace at a neutral site in Ghent, Belgium. President Madison named John Quincy to lead the negotiations, promising, as a reward for success, promotion to the highest post in the foreign service as minister plenipotentiary to Great Britain. Rather than risk having Louisa and seven-year-old Charles Francis travel through areas where fighting might still be taking place, John Quincy left St. Petersburg alone on April 28, 1814, relieved at distancing himself from the scene of his daughter's death.

By the time John Quincy had crossed out of Russia, the Russian, Prussian, and other armies allied against Napoléon had captured Paris and

forced the French army to surrender. Napoléon abdicated and accepted exile on the tiny isle of Elbe, in the Mediterranean Sea off the Italian west coast. Louis XVIII, the dead Louis XVI's younger brother, acceded to the French throne, freeing 14,000 British troops to sail for North America for a massive land and sea attack against the United States. Even as British and American peace negotiators were preparing to meet in Europe, British ships began shelling U.S. coastal cities, allowing British troops to seize Fort Niagara and take control of Lake Champlain. Coastal raids devastated the entrance to the Connecticut River, Buzzard's Bay in Massachusetts, and Alexandria, Virginia, just across the Potomac River from Washington City. The United States seemed helpless to respond. The government was bankrupt and the President impotent, with no command of his armed forces, no credit with Congress, and little influence over or respect from the American people. Everything he said or did only alienated more of his countrymen. He coaxed Congress into reimposing the Embargo Actâand almost starved the people of Nantucket Island. The embargo so devastated the New York and New England economies that state leaders again threatened secession to negotiate a separate peace with England. Northern merchants openly defied the President and federal law by trading at will with the enemy across the Canadian borderâand with British vessels that sailed unimpeded in and out of New England ports.

forced the French army to surrender. Napoléon abdicated and accepted exile on the tiny isle of Elbe, in the Mediterranean Sea off the Italian west coast. Louis XVIII, the dead Louis XVI's younger brother, acceded to the French throne, freeing 14,000 British troops to sail for North America for a massive land and sea attack against the United States. Even as British and American peace negotiators were preparing to meet in Europe, British ships began shelling U.S. coastal cities, allowing British troops to seize Fort Niagara and take control of Lake Champlain. Coastal raids devastated the entrance to the Connecticut River, Buzzard's Bay in Massachusetts, and Alexandria, Virginia, just across the Potomac River from Washington City. The United States seemed helpless to respond. The government was bankrupt and the President impotent, with no command of his armed forces, no credit with Congress, and little influence over or respect from the American people. Everything he said or did only alienated more of his countrymen. He coaxed Congress into reimposing the Embargo Actâand almost starved the people of Nantucket Island. The embargo so devastated the New York and New England economies that state leaders again threatened secession to negotiate a separate peace with England. Northern merchants openly defied the President and federal law by trading at will with the enemy across the Canadian borderâand with British vessels that sailed unimpeded in and out of New England ports.

Recognizing the Embargo Act as a failure and a personal humiliation, Madison asked Congress to end the charade and repeal it. Congress erupted into cheers and overwhelmingly agreed. Congressmen stopped cheering in early August, however, and fled for their lives when a British fleet sailed into Chesapeake Bay. Some 4,000 British troops landed and set up camps along the Patuxent River near Benedict, Maryland, about forty miles southeast of Washington and sixty miles south of Baltimore. Within days they were on the banks of Indian Creek outside Washington at Bladensburg. As the British forded the stream, the shrill scream of rockets pierced American skies for the first time in history, sending bolts of fire into the midst of defending militiamen. To the terror-stricken Americans, the heavens had unleashed

the stars.

p

Their front line broke and fled in panic. With bugler retreats piercing the air, 2,000 Americans sprinted away, tripping over and trampling each other to escape the advancing British, never firing a shot at the enemy.

the stars.

p

Their front line broke and fled in panic. With bugler retreats piercing the air, 2,000 Americans sprinted away, tripping over and trampling each other to escape the advancing British, never firing a shot at the enemy.

A few hours later, British troops entered Washington and began an all-night spree of destruction, burning all public buildings to punish the American government for having burned the public buildings in York. The British spared most private property in the city, although they set fire to four homes whose owners repeatedly shot at passing redcoats. They also spared the Patent Office, as it contained models of inventions and records, which the British commander deemed private property that might well belong to British as well as American patent holders.

A storm the following morning brought bursts of heavy winds that sent flames flying erratically in all directions and forced the British to withdraw to their boats on the Patuxent River.

As British troops burned Washington, British government negotiators sat down with their American counterparts in Ghent to negotiate an end to the warâunaware, of course, of the flames consuming Washington. Joining John Quincy was Kentucky congressman and Speaker of the House Henry Clay, who, like John Quincy, was a fierce champion of manifest destiny. Virginia-born and self-educated, Clay believed in what he called the “American System,” with Americans settling the entire continent and the federal government underwriting a network of roads, canals, and bridges for a comprehensive transportation system. He also favored erecting a tariff

wall to protect American manufacturers from foreign competition in domestic markets. He arrived in Ghent unprepared to yield to British pretensions to governance over the seas.

wall to protect American manufacturers from foreign competition in domestic markets. He arrived in Ghent unprepared to yield to British pretensions to governance over the seas.

Also a champion of westward expansion was former Pennsylvania senator Albert Gallatin. Born and educated in Geneva, Switzerland, he and John Quincy had become good friends in the Senate, and Gallatin went on to become U.S. secretary of the Treasury under Jefferson for eight years. Delaware senator James Bayard, a Federalist, and career diplomat Jonathan Russell, the new American minister to Sweden, made up the rest of the delegation.

Although President Madison had purposely appointed members from all sections of the nation, they presented a united front at the negotiating table behind John Quincy, who was the most experienced diplomat in the group and America's reigning authority on European affairs. And despite their cultural and regional differences, they meshed together magnificently, sharing a rented house, whose servants provided for their needs as efficiently as the staff of a hotel. Although John Quincy took umbrage at Clay's all-night card parties, they found so much in common politically that they became good friends.

“There is on all sides a perfect good humor and understanding,” John Quincy wrote to Louisa in one of his weekly letters to her. “We dine all together at four and sit usually at table until six. We then disperse to our several amusements and avocations. Mine is a solitary walk of two or three hoursâsolitary because I find none of the other gentlemen disposed to join me at that hour. They frequent the coffee houses, reading rooms and the billiard tables. We are not troublesome to each other.”

13

13

Both sides began negotiations from positions of strength and weakness. In North America, British coastal raids had pushed the Americans behind their borders, and the superior British army threatened to invade at a time when the American government was bankrupt, unable to pay or rearm its troops. Clearly, the Americans wantedâand neededâpeace. Britain, however, was just as eager for peace. Her forces had just fought a brutal war

in Europe, but with Napoléon alive in Elbe, the British government realized he might return to France and fire up his troops again. Britain also faced possible conflict with Russia, which, like the United States, was demanding freedom of the seas but, unlike the United States, had the oceangoing fire power to attack British ships. In short, Britain did not want to drain its resources in another long war in the American wilderness where it knew from experience it could never score a decisive victory.

in Europe, but with Napoléon alive in Elbe, the British government realized he might return to France and fire up his troops again. Britain also faced possible conflict with Russia, which, like the United States, was demanding freedom of the seas but, unlike the United States, had the oceangoing fire power to attack British ships. In short, Britain did not want to drain its resources in another long war in the American wilderness where it knew from experience it could never score a decisive victory.

The Americans sat down with demands for an end to impressment, which John Quincy termed nothing less than slavery, but before the talks even got under way, the end of the war in Europe left Britain with no need to expand its navy, and it voluntarily ended the practice. John Quincy's other demands included an end to British blockades as well as British depredations on the high seas and recognition of freedom of the seas for neutral ships. John Quincy also demanded compensation for British depredations on American ships during the long Anglo-French war. British negotiators not only rejected his demands but countered with demands of their own, including a southward revision of the Canadian boundary with the United States by about 150 miles. The British also demanded that the United States cede most of Maine to Canada and agree to demilitarization of the Great Lakes and establishment of a huge Indian-controlled buffer zone across present-day Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, Indiana, and Ohio. The British also wanted to end American fishing rights off the Canadian Atlantic coast unless Americans granted Britain an equivalent privilege, such as navigation rights on the Mississippi River. John Quincy rejected all the British demands, and as negotiations dragged on, each side backed away or increased its demands, according to news from American battlefields, with British negotiators stiffening after the burning of Washington.

In America itself, the press and public had unleashed a torrent of abuse on President Madison after the British burned the federal capital, but Secretary of State Monroe emerged as a hero, and the President appointed him acting secretary of war. Monroe mobilized the nation, calling in militia from other states, ordering and distributing supplies, and setting up an

intelligence system and teams of riders to transmit intelligence to his headquarters. He acted to protect other parts of the country as well, sending a message to General Andrew Jackson in Mobile, Alabama, to take 1,000 troops to defend New Orleans against attack. He promised Jackson 10,000 additional men, then sent express messages to the governors of Tennessee and Kentucky to send militiamen and volunteers to New Orleans. Ignoring the Constitution, Monroe essentially seized the reins of government from the President and Congress, intimidating private banks and municipal corporations into lending him more than $5 million on his own signature to pay and arm more troops.

intelligence system and teams of riders to transmit intelligence to his headquarters. He acted to protect other parts of the country as well, sending a message to General Andrew Jackson in Mobile, Alabama, to take 1,000 troops to defend New Orleans against attack. He promised Jackson 10,000 additional men, then sent express messages to the governors of Tennessee and Kentucky to send militiamen and volunteers to New Orleans. Ignoring the Constitution, Monroe essentially seized the reins of government from the President and Congress, intimidating private banks and municipal corporations into lending him more than $5 million on his own signature to pay and arm more troops.

Â

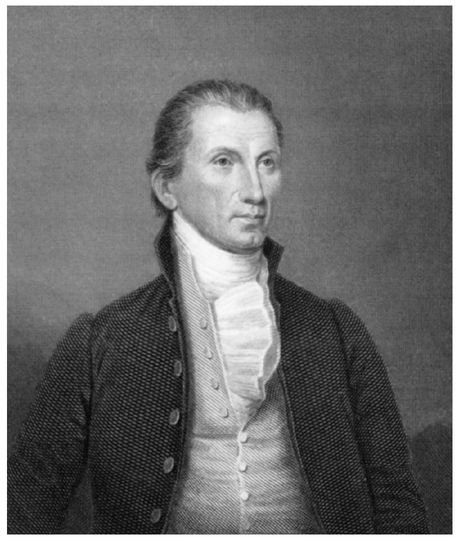

Secretary of State James Monroe named John Quincy Adams American minister to Russia, then lead peace commissioner at talks in Ghent, Belgium, to end the War of 1812 with Britain.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Other books

The 25th Hour by David Benioff

A Ton of Crap by Paul Kleinman

We Are Pirates: A Novel by Daniel Handler

Rift by Kay Kenyon

The Sons of Heaven by Kage Baker

The Hallowed Ones by Bickle, Laura

Second Chance Bride (Rapid Romance Short Stories) by Kelly, Krystal

Snatchers (Book 9): The Dead Don't Scream by Whittington, Shaun

A Special Kind of Family by Marion Lennox

Blood Money by Franklin W. Dixon