John Quincy Adams (42 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

“Gracious heavens, my dear Sir,” an outraged Virginian exclaimed in reaction to John Quincy's embrace of the Africans' defense. “Your mind is diseased on the subject of slavery. Pray what had you to do with the captured ship? . . . You are great in everything else, but here you show your weakness. Your name will descend to the latest posterity with this blot on it: Mr. Adams loves the Negroes too much,

unconstitutionally

.”

5

unconstitutionally

.”

5

Before the case reached the Supreme Court, seventy-three-year-old John Quincy won reelection to the House by a two-to-one majority, while sixty-eight-year-old General William Henry Harrison, hero of the Indian wars, defeated President Martin Van Buren in the presidential election.

“The life I lead,” John Quincy grumbled to his diary as he returned to Washington for double duty in Congress and before the Supreme Court, “is trying to my constitution and cannot be long continued.”

My eyes are threatening to fail me. My hands tremble like an aspen leaf. My memory daily deserts me. My imagination is fallen into the sear and yellow leaf and my judgment sinking into dotage. . . . Should my life and health be spared to perform this service . . . then will be a proper time for me to withdraw and take my last leave of the public service.

6

6

Before the

Amistad

appeal began, John Quincy received a letter from one of his new African clients, a member of an obscure tribe, the Mendi. He had had no knowledge of English before languishing in Connecticut jails for two years:

Amistad

appeal began, John Quincy received a letter from one of his new African clients, a member of an obscure tribe, the Mendi. He had had no knowledge of English before languishing in Connecticut jails for two years:

“Dear Friend Mr. Adams,” the letter began.

I want to write a letter to you because you love Mendi people and you talk to the Great Court. We want you to ask the court what we have done wrong. What for Americans keep us in prison. Some people say Mendi people crazy dolts because we no talk American language. Americans no

talk Mendi. Americans crazy dolts? . . . Dear friend Mr. Adams you have children and friends you love them you feel very sorry if Mendi people come and take all to Africa. . . . All we want is make us free.

7

talk Mendi. Americans crazy dolts? . . . Dear friend Mr. Adams you have children and friends you love them you feel very sorry if Mendi people come and take all to Africa. . . . All we want is make us free.

7

Â

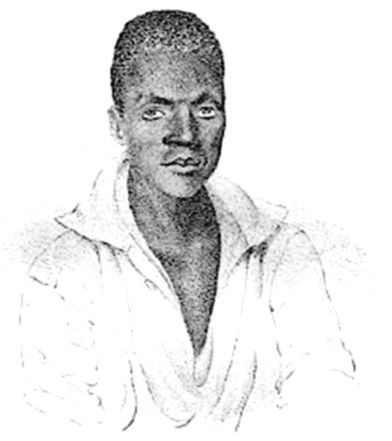

Congolese chief Cinque masterminded the killing of the

Amistad

captain but knew too little about navigation to prevent the crew from sailing into American waters, where the Africans on board were captured and brought to trial as escaped slaves.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Amistad

captain but knew too little about navigation to prevent the crew from sailing into American waters, where the Africans on board were captured and brought to trial as escaped slaves.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

On February 22, 1841, John Quincy walked from his house to the Supreme Court, which sat in the east wing of the Capitol beneath the Senate floor. It was George Washington's birthdayâthe Founding Father whom John Quincy most revered after his own father and who had launched John Quincy's career in public service. Uncompromising southern slaveholders made up the majority of the nine judges, and John Quincy knew them all. In the minority were Joseph Story of Massachusetts, a former Harvard law professor, and Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, a Maryland slaveholder who would later free his slaves. After the prosecution demanded that the government return the

Amistad

Negroes to the Spanish minister for restoration to their “owners,” Roger Baldwin argued for the defense: “The American

people,” he declared, “have never imposed it as a duty upon the government of the United States to become actors in an attempt to reduce to slavery men found in a state of freedom by giving extraterritorial force to a foreign slave law.” The prosecuting attorney replied that slaves “released from slavery by acts of aggression” do not lose their status as the property of their rightful owners “any more than a slave becomes free in Pennsylvania who forcibly escapes from Virginia.”

8

Amistad

Negroes to the Spanish minister for restoration to their “owners,” Roger Baldwin argued for the defense: “The American

people,” he declared, “have never imposed it as a duty upon the government of the United States to become actors in an attempt to reduce to slavery men found in a state of freedom by giving extraterritorial force to a foreign slave law.” The prosecuting attorney replied that slaves “released from slavery by acts of aggression” do not lose their status as the property of their rightful owners “any more than a slave becomes free in Pennsylvania who forcibly escapes from Virginia.”

8

The next day, February 24, John Quincy rose to address the court. “The courtroom was full, but not crowded,” he noted, “and there were not many ladies. I had been deeply distressed and agitated till the moment when I rose, and then my spirit did not sink within me. With grateful heart for aid from above . . . I spoke four hours and a half, with sufficient method and order to witness little flagging of attention by the judges.”

9

9

“Justice,” he began, “as defined in the Institutes of Justinian nearly 2,000 years ago . . . is the constant and perpetual will to secure every one his own right.”

I appear here on behalf of thirty-six individuals, the life and liberty of every one of whom depend on the decision of this court. . . . Thirty-two or three have been charged with the crime of murder. Three or four of them are female children, incapable, in the judgment of our laws, of the crime of murder or piracy or, perhaps, of any other crime. . . . Yet they have all been held as close prisoners now for the period of eighteen long months.

10

10

John Quincy told the justices of his distress in prosecuting the government of his own nation before the nation's highest court and, indeed, “before the civilized world.” But, he said, it was his duty. “I must do it.”

The government is still in power. . . . The lives and liberties of all my clients are in its hands. . . . The charge I make against the present executive administration is that in all their proceedings relating to these unfortunates, instead of that justice which they were bound not less than this

honorable court itself to observe, they have substituted sympathy!âsympathy with one of the parties in this conflict and antipathy to the other. Sympathy with the white; antipathy to the blackâand in proof of this charge, I adduce the admission and avowal of the secretary of state himself.

11

honorable court itself to observe, they have substituted sympathy!âsympathy with one of the parties in this conflict and antipathy to the other. Sympathy with the white; antipathy to the blackâand in proof of this charge, I adduce the admission and avowal of the secretary of state himself.

11

John Quincy went on to read the letter from Secretary of State John Forsyth of Georgia to the Spanish minister in America, citing the owners of the

Amistad

as “the only parties aggrieved”âthat all the right was on their side and all the wrong on the side of their surviving, self-emancipated victims.

Amistad

as “the only parties aggrieved”âthat all the right was on their side and all the wrong on the side of their surviving, self-emancipated victims.

“I ask your honors, was this justice?”

12

12

Far from any “flagging of attention,” the judges sat transfixed for more than four hoursâuntil other needs forced them to adjourn until the next day. That night, however, one of the justices died, and Chief Justice Taney postponed resumption of John Quincy's argument for a week.

The court reconvened on March 1, with John Quincy summarizing his previous argument, then standing for three more hours, reiterating the argument that the

Amistad

Negroes had been free men, seized against their will on their native soil, abducted onto a ship, where they defended themselves and, in doing so, killed their kidnappers. “What . . . would have been the tenure by which every human being in this Union, man, woman, and child, would have held the blessing of personal freedom? Would it not have been by the tenure of executive discretion, caprice, or tyranny . . . at the discretion of a foreign minister, would it not have disabled forever the effective power of

habeas corpus

?”

Amistad

Negroes had been free men, seized against their will on their native soil, abducted onto a ship, where they defended themselves and, in doing so, killed their kidnappers. “What . . . would have been the tenure by which every human being in this Union, man, woman, and child, would have held the blessing of personal freedom? Would it not have been by the tenure of executive discretion, caprice, or tyranny . . . at the discretion of a foreign minister, would it not have disabled forever the effective power of

habeas corpus

?”

Then he came to the end of his presentation. Eschewing secular, legalistic appeals, “Old Man Eloquent” reached into his rhetorical reservoir for spiritual principles he believed he shared with every decent human being. In a moment that ensured his standing in the history of Congress and the Supreme Court, John Quincy Adams told the court that “more than thirty-seven years past, my name was entered and yet stands recorded on both the rolls as one of the attorneys and counselors of this court.”

I appear again to plead the cause of justice, and now of liberty and life, in behalf of many of my fellow men. . . . I stand before the same court, but not before the same judges. . . . As I cast my eyes along those seats of honor and of public trust, now occupied by you, they seek in vain for one of those honored and honorable persons whose indulgence listened then to my voice.

13

13

After a dramatic pause, John Quincy turned his eyes toward the heavens, calling out the hallowed names of the court's early justicesâJohn Marshall, Bushrod Washington, and Thomas Todd of Virginia, William Cushing of Massachusetts and Samuel Chase of Maryland, William Johnson of South Carolina, and Henry Livingston of New York. “Where are they?” he cried out, turning to focus on the faces of each of the justices. “Where?” he paused before lowering his voice to a near whisper.

Gone! Gone! All Gone! Gone from the services which . . . they faithfully rendered to their country. . . . I humbly hope, and fondly trust, that they have gone to receive the rewards of blessedness on high. In taking leave of this bar and of this honorable court, I can only . . . petition heaven that every member of it may . . . after a long and illustrious career in this world, be received at the portals of the next with the approving sentence, “Well done, good and faithful servant; enter thou into the joy of the Lord.”

14

14

As tears flowed down spectators' faces, the prosecuting attorney shook his head in disbelief. He had no idea what John Quincy's closing had to do with the facts of the case, but members of the court understood that by recalling the names of the legendary justices who had helped establish the nation's federal judiciary and, indeed, the nation itself, John Quincy was asking them to abide by standards higher than man's law. Accordingly, the court voted unanimously to give its senior member, Joseph Story, the honor of reading their monumental decision on March 9:

“There does not seem to us to be any ground for doubt that these Negroes ought to be free.”

15

15

“Glorious!” Roger Sherman Baldwin congratulated John Quincy. “Glorious not only as a triumph of humanity and justice, but as a vindication of our national character from reproach and dishonor.”

16

16

John Quincy was equally elated and wrote to his last surviving son, describing his courtroom triumph as one of the most notable events in the family's illustrious history: “The signature and seal of Saer de Quincy to the old parchment [the Magna Carta],” John Quincy told his son, “were . . . almost my only support and encouragement, under the pressure of a burden upon my thought that I was to plead for more, much more than my own life.”

17

John Quincy's plea for the freedom of the

Amistad

captives marked more than six centuries during which he and his forbears had led man's quest for freedom. “Well done, good and faithful servant,” he said to himself.

17

John Quincy's plea for the freedom of the

Amistad

captives marked more than six centuries during which he and his forbears had led man's quest for freedom. “Well done, good and faithful servant,” he said to himself.

A flood of anonymous hate mail awaited John Quincy when he returned home. “Is your pride of abolition oratory not yet glutted?” asked a Virginian. “Are you to spend the remainder of your days endeavoring to produce a civil and servile war? Do you . . . wish to ruin your country because you failed in your election to the Presidency? May the lightening of heaven blast you . . . and direct you . . . to the lowest regions of Hell!”

18

18

While John Quincy continued his daily walks and public swims unmolested, abolitionists paid the price for sending the

Amistad

captives back to their homeland. After they left, a shipload of 135 slaves mutinied aboard the ship

Creole

, bound from Hampton Roads, Virginia, to New Orleans. After killing one of the owners, they directed the crew to sail to Nassau, where British authorities hanged those identified as murderers and freed the rest.

Amistad

captives back to their homeland. After they left, a shipload of 135 slaves mutinied aboard the ship

Creole

, bound from Hampton Roads, Virginia, to New Orleans. After killing one of the owners, they directed the crew to sail to Nassau, where British authorities hanged those identified as murderers and freed the rest.

Although John Quincy had promised himself that if his life and health were spared to defend the men of the

Amistad,

he would “take my last leave of the public service,” his Supreme Court triumph so elated him that he decided the time had not yet come to keep his promise. “Fifty years of incessant active intercourse with the world,” he now said to himself,

Amistad,

he would “take my last leave of the public service,” his Supreme Court triumph so elated him that he decided the time had not yet come to keep his promise. “Fifty years of incessant active intercourse with the world,” he now said to himself,

has made political movement to me as much a necessary of life as atmospheric air. This is the weakness of my nature, which I have intellect enough left to perceive, but not energy to control. And thus, while a remnant

of physical power is left to me to write and speak, the world will retire from me before I retire from the world.

19

of physical power is left to me to write and speak, the world will retire from me before I retire from the world.

19

Â

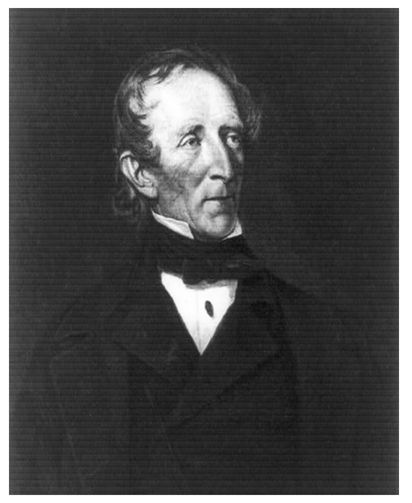

President John Tyler of Virginia was a slaveholder who defended slavery as a quintessential American institution and supported efforts in the House to censure and expel John Quincy Adams.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Other books

Blue Ruin by Grace Livingston Hill

Here Is a Human Being by Misha Angrist

Deep Deliverance: The Deep Series, Book 3 by Z.A. Maxfield

Lucy by Laurence Gonzales

Sawyer by Delores Fossen

A Wedding Wager by Jane Feather

Montana Reunion by Soraya Lane

Woodsburner by John Pipkin

A Woman of Passion by Virginia Henley

All or Nothing by S Michaels