John Quincy Adams (35 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

“The city is thronged with strangers,” complained the southern-born socialite Sarah Seaton, whose brother published the

National Intelligencer

, “and

Yankees

swarm like the locusts of Egypt in our houses, our beds, and our kneading troughs!”

7

National Intelligencer

, “and

Yankees

swarm like the locusts of Egypt in our houses, our beds, and our kneading troughs!”

7

John Quincy was more enthusiastic than Mrs. Seaton and wrote to his “dear and honored father” to tell him of “the event of this day, upon which I can only offer you my congratulations and ask your blessings and prayers.” He signed the letter, “Your affectionate son.”

8

8

The ailing former President answered immediately:

I have received your letter of the 9th. Never did I feel so much solemnity as upon this occasion. The multitude of my thoughts and the intensity of my feelings are too much for a mind like mine, in its ninetieth year. May the blessing of God Almighty continue to protect you to the end of your life, as it has heretofore protected you in so remarkable a manner from your cradle. I offer the same prayer for your lady and your family and am your affectionate father, John Adams.

9

9

Contrary to its affect on former President John Adams, John Quincy's victory appalled many American political leaders, who called it “a mockery of representative government.”

10

Outraged by what he considered the “monstrous union” of Clay and Adams, Jackson cried out, “I weep for the liberty of my country. The rights of the people have been bartered for promises of office. . . . The voice of the people of the West have been disregarded, and demagogues barter them as sheep in the shambles for their own views and personal aggrandizement.”

11

10

Outraged by what he considered the “monstrous union” of Clay and Adams, Jackson cried out, “I weep for the liberty of my country. The rights of the people have been bartered for promises of office. . . . The voice of the people of the West have been disregarded, and demagogues barter them as sheep in the shambles for their own views and personal aggrandizement.”

11

Few members of the Washington political scene doubted that John Quincy had promised, tacitly or otherwise, to reward Clay for his support, and knowing how Clay lusted for the presidency, all assumed that John Quincy would appoint him secretary of state, the stepladder to the presidency for more than two decades. Rumors of “bargain & sale” swept across the political landscape, with some Jackson supporters growling about possible civil war and secession in the West. The mood in the White House turned less than relaxed a few days after the House vote, as President Monroe hosted a reception for the President-elect. The President was chatting with a guest when Andrew Jackson, still recovering from a debilitating illness, thrust his grim, gaunt face through the doorway. Armed as always with two pistols, he snapped his head from side to side until he spotted John Quincy. As the President and other celebrants collectively held their breath, Jackson bounded forward, broke into a warm smile, and, hand outstretched, offered John Quincy his congratulations.

Five days after his election victory, John Quincy announced his decision to appoint Henry Clay as secretary of state.

“So you see,” Andrew Jackson wailed in outrage, “the Judas of the West has closed the contract and will receive thirty pieces of silver. His end will be the same. Was there ever witnessed such a bare-faced corruption in any country before?” Others agreed that John Quincy and Clay had arranged a “corrupt bargain” that undermined the election process and stripped voters of their chosen candidate. New York senator Martin Van Buren, who had backed Crawford's candidacy, was as outraged as Jackson, warning a Kentucky congressman that, in voting for Adams, “you sign Mr. Clay's political death warrant.”

12

Corrupt or not, in appointing Henry Clay secretary of state, John Quincy had also signed his own political death warrant as President.

12

Corrupt or not, in appointing Henry Clay secretary of state, John Quincy had also signed his own political death warrant as President.

On March 4, 1825, “after two successive sleepless nights, I [John Quincy] entered upon this day with a supplication to heaven, first, for my country, secondly for myself and for those connected with my good name and fortunes, that the last results of its events may be auspicious and blessed.”

13

At 11:30 a.m. John Quincy rode to the Capitol in a carriage with his friend Attorney General William Wirt. President Monroe followed in a second carriage, with several companies of militia escorting the two vehicles, along with thousands of citizens who, according to custom then, escorted the President to the inauguration before a joint session of Congress. Missing was Louisa Catherine Adams, whose entertainments had done more to elect John Quincy than he had done for himself. Ill in bed, still suffering the aftereffects of her strep infection, she was unable to face the crowds.

13

At 11:30 a.m. John Quincy rode to the Capitol in a carriage with his friend Attorney General William Wirt. President Monroe followed in a second carriage, with several companies of militia escorting the two vehicles, along with thousands of citizens who, according to custom then, escorted the President to the inauguration before a joint session of Congress. Missing was Louisa Catherine Adams, whose entertainments had done more to elect John Quincy than he had done for himself. Ill in bed, still suffering the aftereffects of her strep infection, she was unable to face the crowds.

John Quincy began his inauguration address in fine fashion, countering Jacksonian polemics by proclaiming, “Our political creed is . . . that the will of the people is the source, and the happiness of the people the end of all legitimate government upon earth.”

14

Greeted with enthusiasm at first, his speech met with ever increasing disbelief, then outright disapproval, as he asked that “all constitutional objections . . . be removed” for construction of interstate roads and canals and other “internal improvement” by the federal government. As he went on, it became clear that his years in the

foreign service, his scholarly pursuits, and his refusal to campaign had left him woefully out of touch with ordinary Americans, and his references to classical civilizations and ancient republics perplexed almost all the members of Congress.

14

Greeted with enthusiasm at first, his speech met with ever increasing disbelief, then outright disapproval, as he asked that “all constitutional objections . . . be removed” for construction of interstate roads and canals and other “internal improvement” by the federal government. As he went on, it became clear that his years in the

foreign service, his scholarly pursuits, and his refusal to campaign had left him woefully out of touch with ordinary Americans, and his references to classical civilizations and ancient republics perplexed almost all the members of Congress.

Â

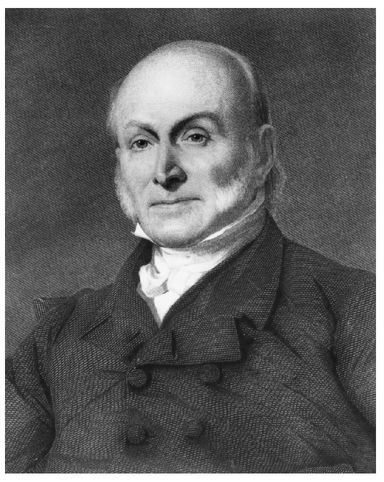

President John Quincy Adams proved the most ineffective President in early American historyâonly to metamorphose into one of the nation's

's

greatest congressmen as a champion of abolition, free speech, and the right of petition.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

's

greatest congressmen as a champion of abolition, free speech, and the right of petition.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

“The magnificence and splendor of their public works,” he waxed in Demosthenic oratory, “are among the imperishable glories of the ancient republics. The roads and aqueducts of Rome have been the admiration of all after ages and have survived thousands of years after all her conquests have been swallowed up in despotism or become the spoil of barbarians.” Although some members misunderstood his reference to barbarians, none failed to recognize his clear intention of assuming powers reserved to the states under the Tenth Amendment of the Constitution.

After John Quincy's speech, Chief Justice John Marshall, a heroic soldier in the Revolutionary War whom John Adams had appointed to the court at the end of his administration, swore in the new President. John Quincy had spent his life training for the presidency and now left to review “military companies drawn up in front of the Capitol” before returning home to join Louisa and “a crowd of visitors” for a two-hour reception. Later, John Quincy went to a White House reception and, after dinner at home, attended the inaugural ball. It was to be one of the last joyous moments of his administration.

He and Louisa spent the next six weeks moving, gradually dismantling their home on F Street and settling into the White House, selling furniture they did not need and buying furniture they did need, including a billiard table for John Quincy. The move was not simple. In addition to caring for their own two younger sons, John II and Charles Francis, the Adamses were still caring for Louisa's orphaned niece and two ill-behaved nephews, one of whom raced right into the White House kitchen to flirt with maids. To add to the family's immediate problems, the Marquis de Lafayette, his son George Washington Lafayette, his secretary Auguste Lavasseur, and his valet Bastien arrived at the White House late in July for a huge banquet. The feast climaxed Lafayette's triumphant yearlong U.S. tour as “the nation's guest” to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of American independence. He had just returned from New England, where he had said farewell to John Adams and now came to bid John Quincy good-bye. The two had known each other since John Quincy was a winsome boy of fifteen living with his father at Benjamin Franklin's residence in Paris. To Louisa's dismay, her husband waxed enthusiastic and insisted that Lafayette and his entourage remain at the White House as his personal guests for the rest of their stay in the United Statesâall of August into September.

“I admire the old gentleman,” Louisa complained, “but no admiration can stand family discomfort. We are all obliged to turn out of our beds to make room for him and his suite.”

15

15

After celebrating Lafayette's birthday on the night of September 6, John Quincy bid Lafayette an official farewell in the peristyle of the White

House. With his cabinet surrounding him and a huge crowd of Lafayette well-wishers looking on, the President spoke with deep emotion: “We shall always look upon you as belonging to us . . . as belonging to our children after us.”

House. With his cabinet surrounding him and a huge crowd of Lafayette well-wishers looking on, the President spoke with deep emotion: “We shall always look upon you as belonging to us . . . as belonging to our children after us.”

Â

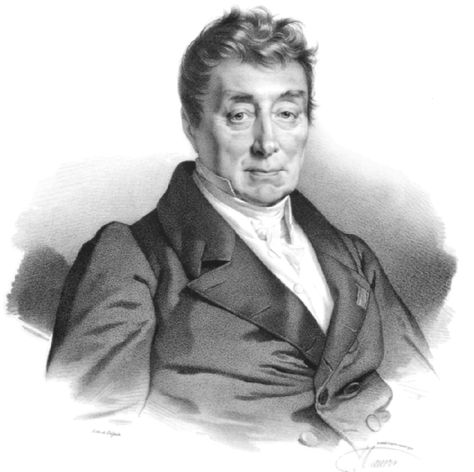

Congress invited sixty-seven-year-old Marquis de Lafayette to tour America as a “guest of the nation” to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the victory at Yorktown. President John Quincy Adams invited Lafayette to stay at the White House during his last weeks in America.

(FROM AN ENGRAVING IN THE CHÃTEAU DE VERSAILLES, RÃUNION DES MUSÃES NATIONAUX)

(FROM AN ENGRAVING IN THE CHÃTEAU DE VERSAILLES, RÃUNION DES MUSÃES NATIONAUX)

You are ours by more than the patriotic self-devotion with which you flew to the aid of our fathers at the crisis of our fate; ours by that unshaken gratitude for your services which is a precious portion of our inheritance; ours by that tie . . . which has linked your name for endless ages of time with the name of Washington. . . . Speaking in the name of the whole people of the United States . . . I bid you a reluctant and affectionate farewell.

16

16

“God bless you, sir,” Lafayette sobbed. “God bless the American people.” He embraced John Quincy and, with tears streaming down his face, rushed back into the White House to collect himself before leaving American shores for the last time.

Lafayette's departure ended the few weeks of civil behavior that the French hero's arrival had provoked among Washington political leaders. Even Vice President Calhoun now turned on John Quincy in a political tidal wave of outrage over what Americans perceived as “the theft of government” and disregard of the popular will. In designating Clay his secretary of state, John Quincy inadvertently provoked the founding of a new political party, with a broad popular base spanning the West and South.

Calling themselves Democrats, the new party set out from the first to cripple John Quincy's administration and ensure his departure after one term. John Quincy tried to forestall the inevitable by offering Jackson a cabinet post as secretary of war, but Jackson all but laughed in his face and refused even to consider serving an administration he was determined to bring down.

While Jackson was building a political party to support his own presidential ambitions, John Quincy held stubbornly to his naive dismissal of political parties as antithetical to union. Even more naively, he refused to take advantage of patronage to put men in office who would support him and his policies. The result was a cabinet and government bureaucracy that, for the most part, worked to undermine both his policies and his chances of winning a second term.

As Jackson and his supporters filled the press with charges headlined “Corrupt Bargain,” John Quincy reacted scornfully, calling the Democratic Party a “conspiracy” against national unity. Henry Clay grew so angry at Virginia senator John Randolph's constant references to a “corrupt bargain” that he challenged Randolph to a duel. Although both men emerged unhurt, Clay managed to send a bullet through Randolph's sleeve.

The threat of duels notwithstanding, Jacksonians in Congress stepped up their obstructionist tactics. When a group of newly independent Latin American nations invited the United States to send representatives to a

conference in Panama to form a pan-American union, Jacksonian congressmen purposely debated the qualifications of John Quincy's appointees until the conference had ended, leaving the American delegates with no conference to attend.

conference in Panama to form a pan-American union, Jacksonian congressmen purposely debated the qualifications of John Quincy's appointees until the conference had ended, leaving the American delegates with no conference to attend.

In addition to his political humiliations in Congress, John Quincy faced unexpected personal humiliation when he and his valet tried rowing across the Potomac River one afternoon, with John Quincy intending to swim back. “Before we got half across,” he explained,

the boat had leaked itself half full and . . . there was nothing on board to scoop up the water. . . . I jumped overboard . . . and lost hold of the boat, which filled with water and drifted away. . . . Antoine, who was naked, had little difficulty. I had much more . . . struggling for life and gasping for breath. . . . The loose sleeves of my shirt . . . filled with water and hung like two fifty-six-pound weights upon my arms.

17

17

Other books

Jane Jones by Caissie St. Onge

Hold Fast by Kevin Major

The Slave Dancer by Paula Fox

Assassin Queen by Chandra Ryan

Heat Exchange by Shannon Stacey

The Cult by Arno Joubert

Traveller by Abigail Drake

The Cove by Catherine Coulter

Laurel and Hardy Murders by Marvin Kaye

A Game Worth Watching by Gudger, Samantha