John Quincy Adams (16 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

“I am still delighted with your facts, your opinions, and your principles,” Vice President John Adams wrote to his son. “You need not be anxious about the succession to the presidency. . . . No man who has been mentioned or thought of, but has a just value of your merits. Even if your father should be the person, he will not so far affect a disinterest as to injure you. If Jefferson, Henry, Jay, Hamilton or Pinckney should be elected, your honor and promotion will be in no hazard.”

31

31

On September 19, 1796, the

American Daily Advertiser

published President Washington's Farewell Address stating emphatically that he would not serve after his second term in office. He also warned Americans of the dangers of divisive political parties at home and urged them to unite in a “fraternal union.” In foreign affairs, he urged keeping the United States a perennially neutral nation, out of foreign wars and with no long-term ties to any foreign nations.

American Daily Advertiser

published President Washington's Farewell Address stating emphatically that he would not serve after his second term in office. He also warned Americans of the dangers of divisive political parties at home and urged them to unite in a “fraternal union.” In foreign affairs, he urged keeping the United States a perennially neutral nation, out of foreign wars and with no long-term ties to any foreign nations.

In the vicious election campaign that followed, Federalists supported Vice President John Adams, who pledged to continue Washington's policy of rapprochement with Britain within the context of neutrality in foreign conflicts. Adams's chief opponent was former secretary of state Thomas Jefferson, who called himself a Democrat-Republican, supported the French Revolution, and sought closer ties to France, regardless of the effects on trade with England.

French minister Pierre August Adet tried to influence the election with pamphlets urging Americans to vote for Jefferson but only succeeded in provoking widespread revulsion against France and eroding the influence of Francophiles in America. Federalists demonized Adet and warned that a Jefferson presidency would be “fatal to our independence, now that the interference of a foreign nation in our affairs is no longer disguised.”

32

The

Connecticut Courant

warned that the French minister was trying to “wean us from the government and administrators of our own choice and make us willing to be governed by such as France shall think best for usâbeginning with Jefferson.”

33

Even Republicans were offended by Adet's meddling, with one of them railing that Adet had destroyed Jefferson's chances for election and “irretrievably diminished the good will felt for his government and the people of France.”

34

32

The

Connecticut Courant

warned that the French minister was trying to “wean us from the government and administrators of our own choice and make us willing to be governed by such as France shall think best for usâbeginning with Jefferson.”

33

Even Republicans were offended by Adet's meddling, with one of them railing that Adet had destroyed Jefferson's chances for election and “irretrievably diminished the good will felt for his government and the people of France.”

34

In the end, John Adams eked out a victory over Thomas Jefferson by three Electoral College votes, by rule relegating Jefferson to the vice presidency.

In the days before the election, Abigail Adams had repeatedly warned her son not to demand any special consideration if his father won, and John Quincy had responded accordingly: “I hope my ever dear and honored mother . . . that upon the contingency of my father's being placed in the first magistracy, I shall never give him any trouble by solicitation for office of any kind.”

Your late letters have repeated so many times that I shall in that case have nothing to expect that I am afraid you have imagined it possible that I might form expectations from such an event. I had hoped that

my mother

knew me better; that she did me the justice to believe that I have not been so totally regardless or forgetful of the principles which my education has instilled, nor so totally destitute of a personal sense of delicacy as to be susceptible of a wish in that direction.

35

my mother

knew me better; that she did me the justice to believe that I have not been so totally regardless or forgetful of the principles which my education has instilled, nor so totally destitute of a personal sense of delicacy as to be susceptible of a wish in that direction.

35

Â

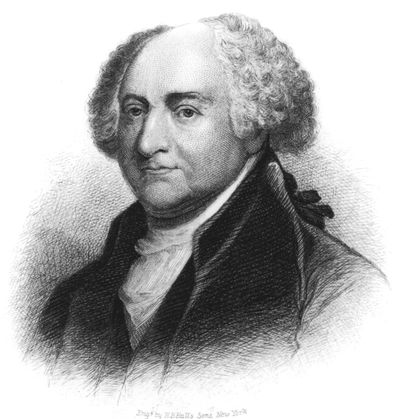

President John Adams, America's second President, ignored charges of nepotism and, on the advice of George Washington, retained his son John Quincy Adams in America's foreign diplomatic corps.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Deeply touched by her son's letter, Abigail Adams sent it on to her husband, who shared it with Washington. The President had, in fact, worried that John Adams's revulsion at nepotism might lead him to dismiss his son from the diplomatic corps, and, indeed, Adams had planned to do just that. After Washington read John Quincy's letter, he told Adams, “The sentiments do honor to the head and heart of the writer, and if my wishes would be of any avail, they should go to you in the

strong hope

[his italics] that you will not withhold merited promotion for Mr. John [Quincy] Adams because he is your son.”

strong hope

[his italics] that you will not withhold merited promotion for Mr. John [Quincy] Adams because he is your son.”

For without intending to compliment the father or the mother . . . I give it as my decided opinion that Mr. Adams is the most valuable public character we have abroad, and that he will prove himself to be the ablest of all our diplomatic corps. . . . The public, more and more as he is known, are appreciating his talents and worth, and his country would sustain a loss if these are checked by over delicacy on your part.

36

36

“Go to Lisbon,” the President-elect wrote to reassure his son, “and send me as good intelligence from all parts of Europe as you have done.”

37

37

After John Quincy told Louisa of his new appointmentâand the enormous increase in his salaryâthey saw no reason to postpone their marriage. He and Thomas packed up their things and shipped everything to Lisbon before sailing to London for the wedding. To their consternation, however, unexpected letters arrived from the secretary of state and from John Quincy's father, the new President, directing him not to proceed to Lisbon but to wait for a commission to the Prussian court in Berlin. Although Berlin was a far more important post than Lisbon, neither John Quincy nor Louisa (nor Thomas, for that matter) was pleased about foregoing Portugal's sunny climes for the long, grey, dismal winters of northern Europe. And John Quincy was livid about having spent $2,500 to ship most of his and Thomas's clothes, furniture, and booksâespecially his booksâto Lisbon.

John Quincy Adams married Louisa Catherine Johnson in an Anglican service in London on July 26, 1797, with his brother and her parents and sisters attending. Two weeks earlier, John Quincy had turned thirty; his bride was twenty-two; and in the course of three idyllic months honeymooning in the English countryside, they wrote to his “Dear and Honored Parents” to share their joy: “I have now the happiness of presenting you another daughter,” John Quincy wrote, “worthy as I fully believe of adding one to the number of those who endear that relation to you. The day before yesterday united us for life. My recommendation of her to your kindness and affection I know will be unnecessary.”

Louisa Catherine appended her own appeal for the Adamses' parental support:

The day before yesterday, by uniting me to your beloved son, has given me a claim to your parental affection, a claim I already feel will inspire me with veneration to pursue the path of rectitude and render me as deserving of your esteem and tenderness. . . . To be respected . . . and to meet the approbation of my husband and family is the greatest wish of my heart. Stimulated by these motives . . . will prove a sufficient incitement never to sully the title of subscribing myself your Dutiful Daughter.

38

38

The joys of their honeymoon suddenly vanished, however, when they returned to London. They knew, of course, that they faced three years of northern European winters in Berlin and enormous difficulties recovering John Quincy's possessions in Lisbon. What they did notâcould notâexpect was an angry mob at the front door of the Johnson mansion in London, screaming for John Quincy to pay thousands of pounds in overdue bills.

CHAPTER 6

A Free, Independent, and Powerful Nation

When John Quincy and his bride crossed London Bridge to the Johnson family mansion after their honeymoon, they expected relatives, friends, and other well-wishers to greet them. Instead, they found a mob of angry, twisted faces, screaming for “money! my money!” During John Quincy and his new wife's absence, Louisa's father's business had collapsed. A cargo-filled ship had sunk in mid-ocean, and one of his partners absconded with company funds. Bankrupt and facing debtors' prison if he remained in England, he fled to America with his wife and children, leaving behind the angry creditors who now blocked John Quincy and Louisa's access to her parents' home.

With no other recourse, Joshua Johnson's creditors demanded that John Quincy cover his father-in-law's debts. The press accused Louisa and her father of having lured the unsuspecting American into marrying a penniless woman to bilk him of his money. “It is forty-three years since I became a wife,” Louisa would recall years later, “and yet the rankling sore is not healed which then broke upon my heart of hearts.”

1

1

Her father's bankruptcy erased the £500 dowry he had pledged to John Quincy and, indeed, gave John Quincy the legal right to recant his marriage vows, but he stood by his bride even as she sank into despondency under the weight of humiliation. As he tried to comfort her, John Quincy faced serious difficulties of his own. Having arranged to transfer his belongings from Lisbon to Berlin, he now learned that the Senate had postponed voting on his appointment to the Prussian court. Although it had unanimously approved his appointment to Lisbon by President Washington, it balked at approving his appointment by President Adams after newspapers assailed the President for nepotism.

Noting that Washington had refused to select even the most distant relatives for office, Boston's

Independent Chronicle

called John Quincy “the American Prince of Wales”âsent abroad “to prosecute his studies.” The newspaper charged that, as the first appointment of his father's administration, “this young man, from an obscure practitioner of the law, has been mounted on the political ladder with an uncommon celerity. Young John Adams's negotiations have terminated in a marriage with an English lady. . . . It is a happy circumstance that he has made no other treaty.”

2

And

Aurora

editor Benjamin Franklin Bache, Benjamin Franklin's grandson and John Quincy's former schoolmate, demanded that President John Adams resign “before it is too late to retrieve our deranged affairs.”

3

Independent Chronicle

called John Quincy “the American Prince of Wales”âsent abroad “to prosecute his studies.” The newspaper charged that, as the first appointment of his father's administration, “this young man, from an obscure practitioner of the law, has been mounted on the political ladder with an uncommon celerity. Young John Adams's negotiations have terminated in a marriage with an English lady. . . . It is a happy circumstance that he has made no other treaty.”

2

And

Aurora

editor Benjamin Franklin Bache, Benjamin Franklin's grandson and John Quincy's former schoolmate, demanded that President John Adams resign “before it is too late to retrieve our deranged affairs.”

3

Abigail was furious at what she called “misrepresentations” and “billingsgate” (vulgar abuse). John Quincy reacted with equal rage. “My old schoolfellow Bache,” he snapped, “has become too thoroughbred a democrat to suffer any regard for ancient friendship or any sense of generosity for an

absent

enemy to suspend his scurrility.”

4

absent

enemy to suspend his scurrility.”

4

Despite Abigail's protests, Bache's “billingsgate” had its desired effect on the Senate, which postponed consideration of John Quincy's Berlin appointment three times before acceding to the President's wishes. John Quincy Adams, his wife Louisa, and his brother Thomas set sail for Hamburg, on October 18, 1797, elated by the prospects of a new adventure. As they put to sea, Louisa added to their collective joy by announcing that she was pregnant.

On November 7, the Adamses reached Berlin's gates, only to be “questioned by a dapper young lieutenant who did not knowâuntil one of his private soldiers explained to himâwho the United States of America were.”

5

5

By the time they reached Berlin, King Frederick William II had died, and John Quincy had to send to Philadelphia for new papers designating him minister plenipotentiary to the new court of King Frederick William III. The papers arrived just before Christmasâas did all the furniture, baggage, and books from Lisbon. With all their personal possessions in hand, John Quincy, Louisa, and Thomas were, at last, able to move from their hotel into a house of their own. A few days later, John Quincy presented his papers at court, where the new king, his three highest ministers, and other dignitaries received him warmly after he demonstrated his fluency in both French and German. Royal society embraced John Quincy and Louisa as an American prince and princess. The pair attended royal banquets and balls, and John Quincy spent three days as a guest of honor at “the grand annual reviews of the troops”âa spectacle of color, parades, and precision marching by tens of thousands of soldiers over hundreds of acres. Always gathering intelligence to relay to the secretary of state, he noted, “There were five regiments of cavalry of twelve hundred men each and ten regiments of infantry of two thousand men each. The troops are in admirable condition and exhibit a very fine appearance.”

6

6

With an elegant houseâand expense accountâJohn Quincy and Louisa opened their doors to European society and looked forward to a festive Christmas, when tragedy struck. Louisa miscarriedânot once, but twice in succession over the next six months. “For ten days,” he wrote to his father, “I could scarcely leave her bedside for a moment.”

7

7

Her miscarriages left her so pale that the queen urged her to use rouge on her cheeks and gave her a box, which John Quincy insisted she must return. Only actresses and “fallen women” wore makeup in New England, and when John Quincy saw his wife wearing rouge as they were to leave for the ball one evening, he told her that “unless I allowed him to wash my face, he would not go.” Louisa said, “He took a towel, drew me on his knee, and all my beauty was washed away.”

8

8

Other books

Authority by Jeff VanderMeer

Day's End by Colleen Vanderlinden

Assignment — Stella Marni by Edward S. Aarons

Edge of Recovery (Love on the Edge) by Molly Lee

The Spy Game by Georgina Harding

Hard As Rock by Olivia Thorne

Sensitive by Sommer Marsden

Peaches 'n' Cream by Lynn Stark

The Portrait by Hazel Statham

Brand New Friend by Mike Gayle