Jornada del Muerto: Prisoner Days (13 page)

Read Jornada del Muerto: Prisoner Days Online

Authors: Claudia Hall Christian

Tags: #shaman, #zombie, #santa fe, #tewa pueblo

I don’t think I can live that way. And I’m

fairly certain George cannot live like that.

We’re leaving in eight

days. We have no choice. We cannot stay here any longer. Prophecy

or no, 480 days is going to have to be enough. We may as well head

to the Pueblo. We have no other place to go.

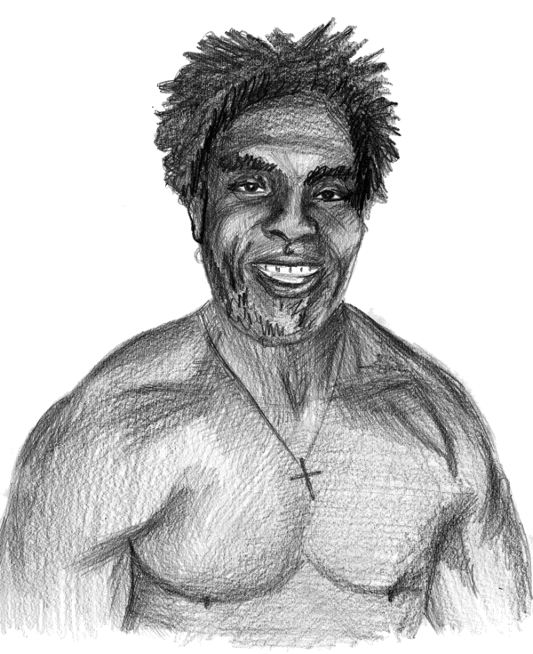

George, self-portrait

11/24/2056

I am proud of myself. I’ve just accomplished

the spiritual equivalent of the children’s game “Telephone.” OK,

“proud” is a little sarcastic.

My brother Earnesto’s spirit has been

hanging around a lot. Somehow, his fate and my journey are linked

together. Or maybe he’s just bored. He could just as easily want to

see his “perfect shaman brother” fall flat on his face. You never

know with brothers.

This morning, I asked him to find our

great-great-grandmother. The fact that we are leaving surrounded by

wasps and with less than 500 wasp-free days worries me. I wanted to

ask great-great-grandmother if we should stay or go.

Earnesto found my mother, who, as I

suspected, was with my father. He found my grandmother, who found

another relative. You can guess how this game went. Someone found

my great-great-grandmother and asked her to appear for me.

My great-great-grandmother was angry when

she appeared. She was told that I needed her help cooking an elk

fillet.

Yep spiritual “Telephone.”

My great-great-grandmother’s spirit came

tearing into the cell. She was furious that I would dare bother her

rest for something so trivial. She stood with finger raised, ready

to give me a tongue lashing when she heard the awful clamor of the

wasps outside the fence. Her face went still, and her finger

dropped. She simply said, “Oh.”

In a matter of moments, we cleared up all

misunderstanding. My great-graet-grandmother was like that in life.

She could switch from rage to calm and loving in a matter of

seconds, especially with her male children. She felt like males

were harder to control. She would have broken herself on me and my

brothers if not for our deep love for her -- and summer camp.

With George watching the door, she and I

held council. I told her everything that had happened. Our less

than 500 wasp-free days, the women, our work to get ready, and

finally our limited access out of the Pen. I even confessed to

starting this journal late.

(She laughed and said she assumed I would

start it late. As she used to joke, I was even late being

born.)

After we held council, she went to review

the situation for herself. When she returned, she asked if I would

tell her everything I knew about the wasps. I told her what little

I knew and what we had learned from the women. I told her about the

disturbing breeding project. I ended saying I thought the noise was

bringing wasps from all over New Mexico and maybe all over the

US.

She was frustrated with me for not keeping

track of how many souls I sent to the afterlife. But how could I

have kept track? There were thousands when the Pen transformed.

Right now, I’m back to sending on thousands of souls a day.

Of course, she would have done a better job.

She did a better job with everything. Better than I. Better than

anyone I’ve ever met. I asked her if human children were being

born, and she didn’t know. I asked her if any of our people

survived. She didn’t know that, either. She said I survived, and

that was good enough for her.

She hadn’t tolerated my whining as a child

and tolerated it much less now.

Then I had the oddest experience. All of my

life, she knew everything. She was the wisest person I’d ever met.

She had an opinion about every little detail of life, especially my

life. More than anything, she’d always known what to do. When I was

stuck, I could ask her, and she’d tell me what to do. If I did what

she said, I was always all right.

Look where going to prison got me. I’m the

only living Tewa.

Today, she didn’t know what to do. She had

no advice for me. She’d missed the rise of the wasps and the death

of the world she’d known. Yes, she’d dropped in to see me, but that

was about me. She had no idea the world had changed so much.

And frankly, I think it terrified her.

Even the rebirth of the streams, mountains,

and prairies was disturbing. For all the decades of believing and

repeating the prophecy, I don’t think she really believed it would

come to pass. Or if she did, I’m not sure she imagined anything

like this.

Who would?

Not one to waste time with sentimentality,

my great-great-grandmother left me to think. George and I went on

about our day. We killed a few thousand wasps, I moved their souls

along, and we had dinner. I’d frankly forgotten about my

great-great-grandmother when she came tearing back into the

cell.

“

You must leave as soon as

possible,” she said.

I must have looked surprised or maybe

stricken, because George turned to me with concern. I repeated what

she’d said. George shook his head. He was as unwilling as I to

leave our gear, our supplies, and the horses behind.

“

How?” I asked.

She smiled as if she was waiting for me to

ask and flew out of the cell. I had to run to keep up with her.

Unable to see her, George panicked and followed close behind me. We

went through our building and out onto the Pen campus. We ran down

the main road until we reached the Administration building. Like a

parade, I followed my great-great-grandmother’s spirit, and George

followed me. We entered the prison administration building, took a

quick turn, and went down another hallway.

Great-great-grandmother

went to the hoarding assistant warden’s office. She stopped behind

the woman’s desk and pointed to the wall. There was a cheap

reproduction on the wall of the historic

Jornada del Muerto

desert. She

pointed to a label on the map, and then to a book that magically

still sat on the assistant warden’s bookshelf. I picked up the

book.

The title read

Part-time Soldiers, Brave Soldiers: The History

of the New Mexican National Guard

by

Oswald Vega. I shrugged. My great-great-grandmother pointed to the

assistant warden’s nameplate. It said: Trudy Vega. This assistant

warden must have been related to the author of the book.

The book pages began to flip in my hand. My

great-great-grandmother was going through the pages until it fell

open to a page that discussed the area next to the prison. Before

the Great Human Transition, that area had housed the New Mexico

National Guard. The properties were adjacent but not connected.

There was a fence in between.

I looked at my great-great-grandmother for a

second, and she nodded. George grunted and gestured to something on

the page. I looked down.

There was a large supply tunnel into the

National Guard area. The black and white photo showed a wide

concrete tunnel lined with every kind of vehicle and even tanks.

The text said the tunnel went from under the National Guards area

to the open road.

“

Emil,” my

great-great-grandmother said, speaking my name.

It had been such a long time since I’d heard

my own name that I didn’t look up. George tapped me on the arm. I

looked at him, and he pointed toward where he’d heard the sound. I

looked at my great-great-grandmother.

“

You must leave as soon as

possible,” she said and disappeared.

I stared at the spot where she had been for

a long time. George touched my shoulder. I looked at him and told

him it was time to go. George pointed to the book, and I nodded. He

shook his head and pointed again. I shook my head because I had no

idea what he was talking about. George gestured for us to check

this new route first, and I nodded.

He started toward the door. At the door to

the assistant warden’s office, he waved for me to follow him.

Without saying another word, we left the assistant warden’s office.

We went through the administration building and out into the

sunshine. Seeing us, the wasps howled!

George took off across the compound. We ran

out of the administration building and down the road toward the

fence. George veered off a few feet from the fence. He went to what

had been a building sometime in the 1900s. The only thing that

remained was the outline of a foundation. Next to the foundation

was a set of six-foot-by-four-foot steel doors set in the dirt.

George pointed to the doors.

The doors were locked closed. There was a

chain thread through the door handles and a heavy steel padlock

holding the chains together. I picked up the lock and shook my

head. We weren’t going in that way.

George made an irritated sound and pointed

to the hinges of the doors. The hinges had rotted in the desert

heat. George lifted the metal doors as one unit and I slipped

underneath into some kind of root cellar. He followed me into the

root cellar. We waited for a few minutes until our eyes adjusted.

Then George took off to the end of the root cellar and turned

right.

Much to my amazement, there was another set

of metal doors. The locks had been broken some time ago. George put

his finger to his lips and pressed his head against the metal

doors. He nodded to me. He glanced at me before opening the doors.

He waved for me to follow him, which I did.

I stepped into a cement box. It was much

darker in this cement box. I could hear George moving around. In a

moment, the overhead lights came on.

I was standing in the National Guard’s

tunnels that went out to the streets. The tunnels were lined with

vehicles of every size. George waved me to the end where a large

four-wheel drive, medium-sized personnel carrier was parked. George

got in and turned the key.

The truck started. George’s grin told me

that he’d used this truck to get our supplies. I walked around it.

It already had puncture-proof tires. I lay down on the ground to

see if George had modified this vehicle. He had. I told him that it

was missing our flame throwers.

He grinned at me and turned off the truck.

He pointed to the wall of the tunnel. There was a line of propane

tanks along the wall. He’d gotten the propane tanks we were using

from here. I nodded. He pointed again. The corner of the tunnel was

an ammunitions depot. We could stock up on ammunition and weapons

here.

He held up two fingers to indicate that he

could have the truck ready to go in two hours.

Two hours.

I didn’t know whether to be excited or

terrified. George just grinned at me.

We have worked for years to get ready for

this exact moment. And now it was time.

While he worked on the truck, I led the

horses into the root cellar. They weren’t thrilled with being

underground, but they’d learned to trust me enough to follow my

lead. They both seemed relieved to make it into the National Guard

tunnel. I turned them over to George, who had rigged a small

trailer for them. The horses would ride inside the trailer behind

the personnel carrier. I returned to our hallway to pack the rest

of our gear.

We are really leaving! I am not taking this

typewriter. We just don’t have the room. I’m hoping to continue

this journal using a pen. (George found me a box of pens in the

National Guard’s supply cabinet.) I will take what’s left of the

coveted ream of paper.

Our journey begins at dawn. Thirty miles to

the Pecos Pueblo.