Joseph M. Marshall III (9 page)

Read Joseph M. Marshall III Online

Authors: The Journey of Crazy Horse a Lakota History

Tags: #State & Local, #Kings and Rulers, #Social Science, #Government Relations, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Cultural Heritage, #Wars, #General, #Native Americans, #Biography & Autobiography, #Oglala Indians, #Biography, #Native American Studies, #Ethnic Studies, #Little Bighorn; Battle of The; Mont.; 1876, #United States, #Native American, #History

Swift Bear’s calm insistence cooled the men’s anger and they left to see to their families. Already the camp of the wounded Conquering Bear had been moved, except for one lodge. The old man’s family stayed with him, afraid to move him because of his wounds. In fact, all the camps relocated further from the fort. In a few days, even Conquering Bear’s lodge was taken down and he was moved to a place of safety where the Sicangu and Oglala had encamped together, carried on a wooden litter by six strong men walking so that he wouldn’t have to endure a jarring ride on a pony drag.

Light Hair and Lone Bear stayed near and watched men like Spotted Tail, Red Leaf, and High Back Bone come and go from the home of Conquering Bear—Crazy Horse, too—helping to make the old man comfortable.

The anger among the younger warriors had not completely faded, however, especially after they had learned that some of the annuities had indeed arrived but that the soldiers were holding them in storage houses. Intent on collecting the annuities, perhaps two hundred armed men rode into the fort early one morning. High Back Bone took Light Hair with him.

If there were Long Knives about, they could not be seen. The fort stood as if deserted. Before long, the storage houses were found, doors were broken down, and bags of food were loaded onto horses. Unchallenged, the men rode away. The old men decided soon after that it would be best to move further from the fort and the Holy Road.

The Oglalas headed north back toward the Powder River country while the Sicangu traveled east toward the Running Water River. Conquering Bear was growing weaker by the day. The farther from the fort and the Holy Road they moved, however, the fresher the air seemed. Trouble seemed far away under the shadow of the western horizon. Crazy Horse and his family stayed among his wives’ Sicangu relatives. High Back Bone also decided to stay with the Sicangu camp to be near the dying Conquering Bear. Lone Bear was with his family in the Hunkpatila camp by now somewhere near the Powder River. Light Hair spent most of his time alone or helping his mothers.

The Sicangu camp finally reached an area near Snake Creek and decided to let the wounded Conquering Bear rest. It was difficult for the people not to think about the incident that was taking the old man’s life. The old men talked of it in the council lodge and the younger warriors talked around their fires under the night sky. But now the flush of anger was wearing away and the men relived the incident as something to be examined from all sides rather than a source of anger and pain.

Light Hair followed High Back Bone to the door of the Conquering Bear lodge on a warm evening. Through the opening, his gaze found the sunken eyes of the dying man—an overall picture so different from that of a man so vital until the shell from the wagon gun knocked him to the ground. There was no light in the old man’s eyes, only a shadow caused by fading life. An immense confusion and sadness washed over the boy. Walking aimlessly back to his own lodge he caught his horse and rode for some far hills.

He rode north from the camp. The horse picked his way over the uneven ground until he reached the top of a long ridge. There was thunder in the west. Light Hair dismounted on the ridge and let the horse graze. Night fell with deeper darkness as he sat on the ridge. Behind him to the east, perhaps three or four days’ travel, was the sand hill country known to him only through the eyes and memories of others. To the north was the country where his mothers had known their childhood. They talked softly about the White Earth and Smoking Earth Rivers, the second a tributary of the first.

Light Hair lay down, keeping his feet to the west in the direction of the thunder and lightning. The Thunders were the source of power. He stared up at the stars.

Morning came, bringing hunger with it. Thirst came as the day grew hot and passed slowly into the afternoon. Once again the clouds rose up behind the western horizon and the Thunders spoke again. Another evening slid into darkness and the Thunders spoke louder and louder, and the lightning turned the land blue-white for a heartbeat each time it flashed. He saw to his horse then curled up against the hunger and growing thirst. Sleep came again sometime in the night.

Hands pulled at him and Light Hair jumped to wakefulness, instinctively moving away from the faces looking down at him.

High Back Bone and Crazy Horse were kneeling over him. The sun was in the morning half of the sky, the land bright. They pulled him to his feet, their faces scowling as they scolded him for his carelessness. The Kiowa and the Pawnee and the Omaha were known to be around at times, they told him.

Light Hair rode silently behind his father and High Back Bone as they returned to the camp.

Reflections:

The Way We Came

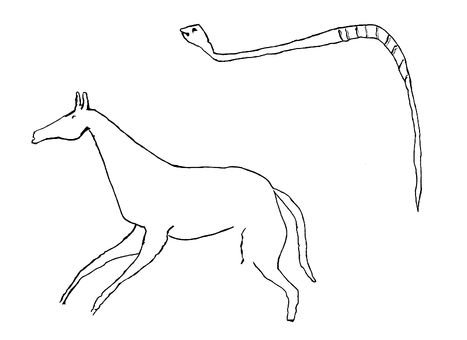

On my wall hangs a color copy of a photograph of a petroglyph.

after Sweem

If the story associated with the petroglyph is true, then the man who carved it was Crazy Horse. A Northern Cheyenne friend of his is believed to have been with him and witnessed the carving of it into a sandstone wall along Ash Creek a few miles southeast of the Little Bighorn River and the Little Bighorn battlefield. The photograph was taken by the late Glenn Sweem of Sheridan, Wyoming—a history buff and a fine, fine gentleman.

The carving is said to have been done a few days before the Battle of the Little Bighorn. I have no reason to doubt the authenticity of the petroglyph and that Crazy Horse was its creator, but then I may feel that way because I

want

it to be real. I have not seen it with my own eyes and never will if the last report I heard is true. The sandstone bluff, I was told, was washed away. Plaster replicas of the wall with the images on it have been made, however.

want

it to be real. I have not seen it with my own eyes and never will if the last report I heard is true. The sandstone bluff, I was told, was washed away. Plaster replicas of the wall with the images on it have been made, however.

Some who have seen the actual petroglyph or the photograph or the plaster replicas believe it to be Crazy Horse’s signature. It is, of course, open to interpretation. I think it was more of a statement than a signature.

The snake, to some Lakota, symbolizes

toka,

or “enemy.” If the carver of this petroglyph was using the snake in this manner, then the horse—and whomever and whatever it represented—was being pursued or followed by an enemy or enemies.

toka,

or “enemy.” If the carver of this petroglyph was using the snake in this manner, then the horse—and whomever and whatever it represented—was being pursued or followed by an enemy or enemies.

At that point in his life, in 1876, Crazy Horse was certainly well aware that he had detractors, men who were envious of his status among the Lakota. When I see the photograph on my wall, I feel as though Crazy Horse was saying

Lehan wahihunni yelo,

or “This is where I am in my life.”

Lehan wahihunni yelo,

or “This is where I am in my life.”

Or perhaps he was simply saying

I was here.

I was here.

Whatever the message, it does reach across from then to now, at least for me.

Crazy Horse came into the world at least four generations ahead of mine. He was born in the early 1840s, perhaps as late as 1845. I was born in 1945. As Lakota males, he and I have much in common. Enough of Lakota culture has survived through the changes during those four generations, fortunately, to allow my generation to identify strongly with his.

My childhood was similar to his in several ways. I grew up in a household where Lakota was the primary language, as did he. I heard stories told by my grandparents and other elders who were part of an extended family, as did he. My maternal grandparents, who functioned as my parents, were very indulgent, as Light Hair’s parents and the adults in his extended family were. I recall vividly the solicitous attention from my grandmother and from all the mothers and grandmothers who were part of the extended family circle, not to mention the women in the community of families in the Horse Creek and Swift Bear communities in the northern part of the reservation. Given these experiences, I know how it was for him as a boy growing up. The society and community and the sense of family—all of which were operative factors in his upbringing—were much the same for me. My 1950s lifestyle was certainly different than his 1850s lifestyle as a consequence of interaction with Euro-Americans, but traditional Lakota values and practices of rearing and teaching children have remained basically intact in the more traditional families and communities of today.

In my early days, as in Crazy Horse’s, every adult in the family’s extended circle and those in the community (village) were teachers, nurturers, and caregivers. The concept of “babysitting” was alive and well because everyone watched over all the children all of the time. In a sense there were no designated or hired “babysitters” because everyone was. Though the biological mother and the immediate family were the primary caregivers, the entire community or village had a role in raising the child. But in traditional Lakota families today these values and practices are still upheld and applied. Furthermore, among us there were and are no orphans. Though one or both biological parents may be lost to the child, someone in the immediate or extended family circle is ready to step in and function as a parent. A friend of mine on the Pine Ridge reservation had a particularly close relationship with his mother. I was surprised to learn later that the woman was, in our contemporary terminology, his stepmother because—as he explained it—his “first” mother had died.

The village itself, however, has changed. In the early days of the reservations in South Dakota, the old

tiyospaye

or family community groups attempted to remain together as much as the system of land ownership would allow. Actually owning the land, as opposed to controlling a given territory, was a new concept. As a consequence of the Fort Laramie treaties, the Lakota (and other tribes of the northern Plains) were “given” collective ownership of enormous tracts of land. Collective ownership—-everyone together owning all of the land—was not too far removed from the entire group or nation maintaining territorial control.

tiyospaye

or family community groups attempted to remain together as much as the system of land ownership would allow. Actually owning the land, as opposed to controlling a given territory, was a new concept. As a consequence of the Fort Laramie treaties, the Lakota (and other tribes of the northern Plains) were “given” collective ownership of enormous tracts of land. Collective ownership—-everyone together owning all of the land—was not too far removed from the entire group or nation maintaining territorial control.

While the Lakota were still conceptually adapting to owning the land, the Dawes or Allotment Act of 1887 changed the rules; it changed collective ownership to individual ownership. Though the implementation of the act took several years because reservations had to be surveyed in sections, quarter-sections, and so on, and the population of adult males (eighteen years and older) counted, the culmination was the allotting of 160-acre tracts to family men and 80 acres to single men. Women were not eligible for initial allotment. Essentially the new system forced Lakota families to take up “homesteading,” and the encampments of old—several families living together—gave way to single families living on their tracts of land. Though the nearest friend or relative might be as close as just over the boundary line, the close physical proximity of living in a village was no more.

Even so, the ancient social more of functioning as a village still persisted. Mere distances could not destroy the sense of belonging to a group or a community. Friends and families came together at every opportunity and to meet every necessity. Dances, weddings, give-away feasts—and until the 1940s, going to the various government issue stations—were some of the reasons to gather together. Traveling by foot, horseback, or in horse-drawn buggies and wagons, the communities clung to as many of the old ways as possible.

Clinging to the old ways was not easy, however. In Light Hair’s boyhood the whites were unwelcome interlopers. At the other end of the hundred-year spectrum, in the 1940s and 1950s, we Lakota were still living under the firm control of the interlopers in the guise of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Government and parochial boarding schools took children from their families, and the process of learning became a group activity motivated by the prospect of punishment for failure rather than the one-on-one mentoring where lessons and achievement were more important than the rules.

Light Hair’s father was free to pursue his calling as a medicine man, but in my boyhood Christianity was telling us that our spiritual beliefs and practices were passé. As late as the 1940s, Indian agents (now called superintendents), frequently at the behest of white priests and pastors, sent Indian police to roust out Lakota medicine men. Their sacred medicine objects such as pipes, gourd rattles, and medicine bundles were confiscated and sometimes destroyed on the spot. It is likely that many of those objects later became museum displays as cultural artifacts. The medicine men were ordered to cease conducting and practicing their spiritual and healing ceremonies. But fortunately for us Lakota of today, our grandparents’ generation by and large employed the “smile and nod” tactic. When raided by Indian police, medicine men would smile and nod to avoid further persecution or even jail time. When the Indian police left they would haul out another pipe or make another one, and they would make sure their ceremonies went further underground.

Other books

The Puzzle by Peggy A. Edelheit

A Collar and Tie (Ganymede Quartet Book 4) by Glass, Darrah

Eleven New Ghost Stories by David Paul Nixon

No Regrets (A Stepbrother New Adult Novella) by Fawkes, Emma

Arsenic and Old Books by Miranda James

Dreamers of the Day by Mary Doria Russell

Out of Mao's Shadow: The Struggle for the Soul of a New China by Philip P. Pan

Tinseltown Riff by Shelly Frome

As Good as Dead by Patricia H. Rushford

Honest Cravings by Erin Lark