Kinglake-350 (5 page)

Authors: Adrian Hyland

Bruce and Margaret Newport, in Chads Creek Road, Strathewen, feel relatively confident of their ability to defend their home. They are well equipped with pumps and tanks, and live a considerable distance from the bush on an Angus beef farm they’ve kept wet and green in preparation for a forthcoming field day. They are experienced country folk. When the fire approaches late that afternoon, Margaret and the children shelter inside while Bruce patrols the boundaries.

Then he watches in horror as the wind tears the roof from the building. ‘The whole thing peeled back like a tupperware lid and came off,’ recalls Bruce. ‘Beams and all.’

The family survive, but only just.

When many survivors look back on Black Saturday, it is the wind that looms largest in their memory. That hot red blast was the engine that powered the juggernaut.

‘It was blowing a bloody gale up on the mountain,’ says Roger Wood. ‘Never seen anything like it. I was driving a two-tonne Pajero, and when I was out in the open it was rocking like a sailboat in a storm.’

To be in an exposed location in the bush that day was to feel that you were in the grip of a protean force: every branch, each leaf and twig was alive and writhing, straining, breaking loose, whipping away. The grasses bowed and rose as if invisible giants were running through them. One firefighter described a large limb caught up in the power lines, how it made him think of the skeleton of a galleon. As he watched it was torn apart, shattered into fragments that speared fifty metres through the air.

In the Kinglake Ranges it was probably worse than most places because of what fire authorities call the Ramp, where the flatlands rise into the foothills and the slope intensifies wind conditions. The result, local fire managers report, is that winds in the ranges are often twice as strong as statewide forecasts.

A big running bushfire is an extraordinarily complex concatenation of events, a synchronicity of fuel, topography, heat, drought and human activity. But it is the wind that causes that frayed conductor on the Pentadeen Spur to snap and come crashing to the ground, sending an electrical charge arcing into the grass.

It is the wind that picks up those first thin fingers of flame and transforms them into something extraordinary, propels them in long, expanding ellipses out into the grasslands, then into the pine and bluegum plantations to the south-east.

Bureau of Meteorology data suggests that the recorded wind reached speeds of up to 120 kilometres per hour. But a raging bush-fire will generate its own tornadic winds, and they can be much more powerful.

Nic Gellie, who modelled the reconstruction of the Kilmore East fire for the Department of Sustainability and Environment, estimated that the wind around the fire was of cyclonic force, hitting speeds of between 150 and 200 kilometres per hour. (There were no weather stations located at the fire front, so these are estimates based upon the damage done at places such as St Andrews and Strathewen, where roofs were torn from houses and massive trees corkscrewed out of the ground.)

But what is wind? And why did it go berserk on Black Saturday?

Around the world, its names are legion and rich with local memory and lore: brickdusters and mistrals, cat’s paws, diabolos, doctors, the Steppenwind. There is the bitter Pittarak that whistles off Greenland’s fields of ice. The suicide-inducing foehns. The fire-driving Santa Anas. The Harmattan, the ‘hot breath of the desert’, the name given by Tuareg nomads to the sirocco and said to derive from the Arabic for ‘an evil thing’.

Humans have struggled to make sense of wind since the dawn of consciousness. The ancient Indians saw it as the breath of life. To the Greeks Aeolus, the Keeper of the Winds, lived on a floating island, and is remembered for giving Odysseus the bag of winds that wreaked havoc on his journey. In Aztec theology, the god Ehecatl employed gentle zephyrs to awaken Mayahuel, the goddess of love, thereby endowing humanity with the gift of love. The Book of Genesis goes even further: when the spirit of God moves over the waters, it appears in the form of wind.

As humanity moved from myth to science, deeper thinkers sought more rational explanations. The Greek philosopher Anaximander suggested that wind was a current formed when mists were burned off by the sun. Meteorologists would say he wasn’t that far from the truth. Our contemporary understanding of wind begins with the sun, and that instinct for balance that underlies the weather.

We think of air—well, we don’t think about it at all as a rule, unless we’re running out of it. But it’s there all the time, it’s the envelope of gases that girds our planet, and within which our respiratory systems have evolved.

You might not envisage air as having weight but it does, of course: that’s what’s pushing into your face when you step outside on a windy day. It is, in fact, surprisingly heavy—the air in a normal room weighs about fifty kilograms. If you had a 25-millimetre tube going from sea level to the top of the atmosphere, the air inside it would weigh about 6.7 kilograms. Each square metre of air bears down with a force equal to a ten-tonne weight, but because the pressure in liquid or gas acts uniformly in all directions and the downward force is countered by an equivalent upward force, we don’t get squashed. When those particles of air develop a collective motion in a particular direction they become what we call wind.

It was the polymath Edmund Halley, he of the comet, who in 1686 first came up with a theory that approximates our contemporary understanding of how that motion works. Halley was struck by the correlation between information from two new sources: the data about air pressure provided by the recently invented barometer and the flow of the planetary winds reported by the mariners of the expanding British Empire. He deduced that the air along the equator was heated by the sun and lifted, to be replaced by cooler air drawn in from the temperate regions on either side of the equator— the trade winds, so crucial to the maritime industry.

Halley’s observations were further refined in 1735 by amateur meteorologist George Hadley, who suggested, correctly, that the winds were affected by the Earth’s rotation: the winds don’t just ascend and run north or south: they tilt. Hadley also proposed that the thermal convection (warm air rising) at the equator is followed by subsidence at higher latitudes, a theory recognised today in the circulation pattern known as the Hadley Cell. Interestingly, Hadley’s equatorial hot-air convection columns descend at around thirty degrees latitude north and south—thereby explaining the location of many of the world’s deserts, from the Sahara to the Great Victorian, the Atacama to the Kalahari.

It was a cluster of those deserts, the ones that compose the vast mulga and spinifex plains of Central Australia, that would forge the terrible winds of Black Saturday.

In early February 2009, Australia was ringed—ringbarked, it almost seemed—by a triumvirate of high- and low-pressure systems. The procession of highs and lows that moves across our TV screens every night makes them seem like separate entities floating up there in the sky, but of course those diagrams represent patterns, not objects. Highs and lows are simply illustrations of the tendency of the molecules in the atmosphere to cluster together and move in a particular direction.

Like any other gas, air reacts when placed under pressure. Think of the air compressed inside a balloon; when given the chance, it automatically strives to achieve equilibrium by rushing to an area of lower pressure—the space outside. The greater the difference in pressure, the greater the rush; the steeper the gradient of decline, the stronger the wind.

The atmosphere is constantly swirling around, rearranging itself in response to the shifting centres of pressure created by solar radiation. These move in great cycles, their constituent air spiralling in towards the centre of low-pressure systems and outwards from highs. One of the outcomes of the Coriolis effect—the ‘centrifugal force’ generated by the Earth’s rotation—is that the air cycling in and out of highs and lows flows in different directions in the different hemispheres. Here in the south, it flows clockwise into low-pressure systems and anti-clockwise around highs.

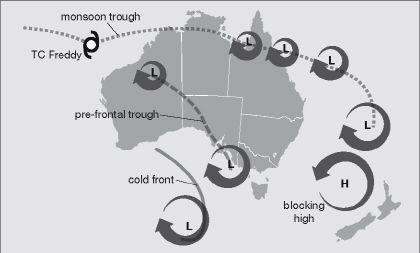

There were two significant lows affecting Australia in the days leading up to Black Saturday. The first was a monsoonal trough over northern Australia. This elongated centre of low pressure drew in vast amounts of moisture-laden air that whipped up deep convection clouds across the Gulf of Carpentaria and into Queensland (causing, ironically, widespread flooding). The ascending air associated with this cyclonic turbulence had to be compensated for by subsiding air elsewhere, and that subsidence was corralled to the south-east.

Then there was a second low over the Southern Ocean. This was drawing cold dense air northwards, pushing against the warmer subtropical air to the north like a giant bulldozer. Since the air in both of these systems was flowing clockwise, the resulting airflow was being compressed, heated, driven down over the parched Central Australian deserts.

But out over the warm waters of the Tasman Sea there was a third weather system, a blocking high so powerful that it would not be budged. This had the effect of locking the lows in place. It was the reason the heatwave lasted as long as it did.

High up in the atmosphere was yet another complicating ingredient in the mix: a subtropical jet stream ripping along at speeds of up to three hundred kilometres per hour. The air caught in the jetstream was subsiding on one side, giving the overall flow a whirling, rotational momentum that was ultimately transferred into the surface winds tearing over and into the ground below.

Weather systems on the morning of February 7

These three weather systems—the monsoonal low with air flowing out from the upper reaches of its convection clouds; the southern low with its advancing wall of cold air; the blocking high—combined to squeeze the airflow of the subtropical jet stream downwards over south-eastern Australia. As the dry air descended it became hotter and faster: by the time it reached the surface, it was like the blast from a furnace.

As fire scientist Liam Fogarty, Assistant Fire Chief with the dSE, put it:

The state was being squeezed tighter and tighter and the wind kept getting stronger. But the front over the Tasman was just sitting there, saying, ‘you can keep coming all you like, but I’m not moving.’ We in Victoria were caught in the pressure point between them.

The horrific twelve-year drought would have added to the heat as well, and was doubtless the reason why so many temperature records were broken. The ground was so parched and hard-baked that there was little evaporation to ameliorate the conditions. In wetter years, residual moisture in the soil and vegetation would have had a moderating effect, reducing the temperature. Now solar radiation heated the ground and was returned directly back into the atmosphere in the form of high-powered dry convective thermals, which further warmed and dried the air.

The confluence of these phenomena amounted to a massive blast of sun-dried, super-heated air being driven down to the south-east, into what fire historian Stephen Pyne calls the ‘fire flume’.

A flume, in the common sense of the word, is a man-made structure: a deep, narrow defile through which a fluid—usually water—is channelled. A flume might be constructed to transport timber, to divert water from a dam or power a water wheel: a mill race is a flume. But in Pyne’s elegant trope, it is not water that is channelled, it is wind.

The eastern ranges act like wings, shepherding heated air southwards, concentrating energy; the variable soil and precipitation produce vast amounts of fuel on the ground. Topography, botany and weather: these interwoven forces provide the dynamism that makes the great fire triangle of south-eastern Australia—its corners at Botany Bay, Port Phillip Bay and the Eyre Peninsula—the most fire-prone location on Earth.

In an observation tower at Kangaroo Ground, twenty kilometres south of Kinglake, a fire spotter named Colleen Keating watches in horror as fire comes rolling down from the north. She passes on the information to her Incident Control Centre, assuming it is being acted upon.

It isn’t.

The CFA fire management policy is that a blaze remains the responsibility of the district in which it ignites until it is formally passed over to whatever region it enters. This fire, having commenced in Region 14, is initially the responsibility of the Kilmore Incident Control Centre. As it roars south-east, it crosses CFA boundaries and moves into the jurisdiction of the Region 13 Centre at Kangaroo Ground, the office responsible for the Kinglake Ranges.

But at Kilmore things are in a state of chaos. Communication systems—phones, computers, faxes—are completely swamped by incoming reports, many of them contradictory, as the managers struggle to cope with the unbelievable speed of the inferno. Fire-prediction maps are drawn up and ignored; warnings are not issued until the relevant communities are already destroyed. Most critically, due to the collapse of the communication system, responsibility for the fire is never formally handed over to Kangaroo Ground. There are staff at Kangaroo Ground who can see disaster looming, who beg for warnings to be issued to the towns in its path, but they are not heeded. The Incident Controller at Kangaroo Ground refuses to take action until the correct procedures have been followed and responsibility for the fire is formally handed over.

The control centre does issue warnings to SP Ausnet, the power company, that their power lines in Kinglake are in danger, but not to the people who live around those power lines. Warning notices are drafted but not released.

By 2.11 pm, smoke has been sighted at the foot of Mount Disappointment, just inside the boundaries of the Kinglake National Park. It crests this ridge about an hour later, sending out an incendiary barrage that begins raining down upon the rolling, heavily populated foothills at the base of the Kinglake Ranges.

Everywhere along its path, local brigades turn out to try and stop it. They hit it with all their resources: they water-bomb it, clear firebreaks, muster more than ninety appliances.

Everywhere they fail.

The fires of February 7 were a freak of nature, people concede that. They moved at a furious, unprecedented speed and spotted over record distances. But few who were in the Kinglake Ranges that day are ready to forgive the failure of the authorities to warn anybody in the path of the fire—even those responsible for community safety, the local emergency services personnel, the fire captains and coppers—that it was coming. A year later, many of those who were affected by the fire still struggle to contain their anger.

‘We know those people,’ says Kinglake West firefighter and Deputy Group Officer Chris Lloyd. ‘We talk to them every day. A simple phone call could have made all the difference.’

Mike Nicholls, the captain of Panton Hill CFA, is even more cutting. ‘I still feel angry when I think about it. There were a lot of things we could have done if we’d had a warning. I’m sure it would have saved some lives.’

Nicholls is one of those extraordinary characters who make your local CFA brigade the eclectic body it is. Originally trained as a plumber, he went off to university and has remained in academia. In 2009 he was a professor in the Psychology Department at Melbourne University. He manages to combine the tradie’s practical skills and blunt speaking with the analytical powers of the academic.

The way the disaster unfolded confirmed many of his doubts about the organisational structure of the CFA. His criticism is in no way aimed at the local volunteers, who were out there risking their lives to fight the fire with minimal information; it is the upper echelons about whom he is most scathing.

‘Some of them are not the sharpest tools in the shed,’ he says. ‘They employ at the bottom and then promote them. I’d like to think I know a bit about these things. You can train someone all you like— at the end of the day you’re not going to change their personality or intelligence. Those in charge of the ICCs didn’t have the sense—or the balls—to make decisions on their own.’

The Victorian Country Fire Authority is an organisation that epitomises something unique, almost elemental, in the nation: it is volunteer-based, locally focused, practical, down to earth. It is, at brigade level at least, a bullshit-free zone: you either do the job or you don’t. ‘If you don’t like it,’ one member politely explains, ‘you can pack up and piss off; nobody forces you to be here.’

There have been improvised fire-fighting groups since the beginning of European settlement, but the Victorian CFA arose as a result of recommendations by the Royal Commission into the Black Friday fires of 1939. The outbreak of the Second World War delayed its creation, and it formally commenced operations in April 1945.

Perhaps because many of those who made up the first units shared a military background, it adopted a structure not unlike the armed forces: each brigade has a captain, who is supported by a number of lieutenants. Where it parts company with the military is in the fact that its officers are elected by their fellow members.

One of its strengths is the autonomy of its individual brigades: they know their communities and are authorised to make decisions about their safety. They know the hot spots and the death traps, the bog holes and the back roads; they know where to find water when they need it, they know which old people are living on their own, which women are home from hospital with newborn babies.

There are over 1200 separate brigades spread across the state. Between them, they can muster some 58,000 volunteers. Whenever there is a threat or tragedy in rural Victoria—a fire, a flood, a traffic accident, a lost child, a fallen power line—you can be sure that somewhere nearby, a group of men and woman will be running from their workplaces and homes, scrambling onto their ‘Berts’—big, expensive red trucks—and rushing to the scene.

There’s generally a vehicle out the front door within five minutes of the call coming in. On a blow-up day like Black Saturday, the minutes become seconds. Most brigades have people geared up and waiting by the trucks.

The CFA brigades in the ranges are nothing if not diverse. Their volunteers range in age from sixteen to…too polite to ask. Their occupations show a similar diversity—there are tradies and businessmen, lawyers and nurses, office and hospitality workers— and they have a wide variety of reasons for joining. Some are there for the excitement, some are there for the friendship or from a love of working with heavy equipment. All are there because they think it’s a worthwhile thing to do for the community. No one is there for the money.

There is an element of friction between the paid and the volunteer firefighters, with the latter sometimes mocked as a kind of dad’s army. But in practice the experience and diversity in the local brigade is a strength. The truck that comes roaring up your road in the event of a crisis could be crewed by a group of your neighbours whose life skills include metal work or electrical engineering, first aid, plumbing, meteorology, land management, vet science, business.

Some might seem irrelevant: what use is a human resources manager in an emergency, for instance? But if you observe the response to a critical incident up close, you will be struck by what a complex operation it is, how crucial is the ability to coordinate people and resources, to think logically, make snap decisions.

The CFA is also an equal opportunity employer (albeit an honorary one): many of the firefighters out there driving trucks and operating chainsaws on Black Saturday were women, as were many of the crew leaders and captains. At one of the most critical moments of Black Saturday, when fire was directly impacting the National Park Hotel and the hundreds of people sheltering beside it, the firefighter standing alone out in the darkness with a spluttering 38 millimetre hose in hand was a seventeen-year-old schoolgirl who had just received a pager message that her own home—with the rest of her family in it—was under attack.

Each CFA firefighter completes, as a minimum, a six-month training course in wildfire management. One of the first things new members learn is how to save their own lives in a burnover, when the vehicle is overwhelmed by fire. Firefighters, almost by definition, often find themselves in the most dangerous part of the inferno, and you can’t save anybody else if you can’t save yourself. The routine is to jettison anything explosive—jerrycans, chainsaws—crouch down and cover up as best you can, spray a fountain of water over the truck, often with a hand-held hose, and pray that the water outlasts the fire. For a firie this is the most terrifying experience of all: they all know the names of locations—Upper Beaconsfield, Linton—where entire crews have perished in recent years. But burnover is, in fact, a rare occurrence. There’s many a firefighter who’s been on the job for twenty, thirty years and never experienced one.

There are two fire brigades on the mountain—at Kinglake and Kinglake West—with four trucks between them. In the next few hours, all four vehicles will be burnt over.