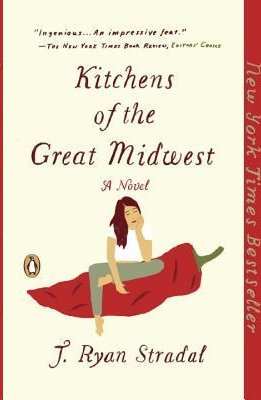

Kitchens of the Great Midwest

Read Kitchens of the Great Midwest Online

Authors: J. Ryan Stradal

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

A Pamela Dorman Book / Viking

Copyright © 2015 by J. Ryan Stradal

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

ISBN 978-0-698-19651-3

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

Mom’s Chicken Wild Rice Casserole

To Karen

Who always did the best with what she had

L

ars Thorvald loved two women. That was it, he thought in passing, while he sat on the cold concrete steps of his apartment building. Perhaps he would’ve loved more than two, but it just didn’t seem like things were going to work out like that.

That morning, while defying a doctor’s orders by puréeing a braised pork shoulder, he’d stared out his kitchen window at the snow on the roof of the Happy Chef restaurant across the highway and sung a love song to one of those two girls, his baby daughter, while she slept on the living room floor. He was singing a Beatles song, replacing the name of the girl in the old tune with the name of the girl in the room.

He hadn’t told a woman “I love you” until he was twenty-eight. He didn’t lose his virginity until he was twenty-eight either. At least he’d had his first kiss when he was twenty-one, even if that woman quit returning his calls less than a week later.

Lars blamed his sorry luck with women on his lack of teenage romance, and he blamed his lack of teenage romance on the fact that he was the worst-smelling kid in his grade, every year. He stunk like the floor of a fish market each Christmas, starting at age twelve, and even when he didn’t smell terrible, the other kids acted like he did, because that’s what kids do. “Fish Boy,” they called him, year round, and it was all the fault of an old Swedish woman named Dorothy Seaborg.

• • •

On a December afternoon in 1971, Dorothy Seaborg of Duluth, Minnesota, fell on the ice and broke her hip while walking to her mailbox, disrupting the supply line of lutefisk for the Sunday Advent dinners at St. Olaf’s Lutheran Church. Lars’s father, Gustaf Thorvald—of Duluth’s Gustaf & Sons bakery, and one of the most conspicuous Norwegians between Cloquet and Two Harbors—promised everyone in St. Olaf’s Fellowship Hall that there would be no break in lutefisk continuity; his family would step in and carry on the brutal Scandinavian tradition for the benefit of the entire Twin Ports region.

Never mind that neither Gustaf, his wife, Elin, nor his children had ever even seen a live whitefish before, much less caught one, pounded it, dried it, soaked it in lye, resoaked it in cold water, or done the careful cooking required to make something that, when perfectly prepared, looked like jellied smog and smelled like boiled aquarium water. Since everyone in the house was equally unqualified for the job, the work fell to Lars, age twelve, and his younger brother Jarl, age ten, sparing the youngest sibling, nine-year-old Sigmund, but only because he actually liked the stuff.

“If Lars and Jarl don’t like it,” Gustaf told Elin, “I can count on them not to eat any. It’ll eliminate loss and breakage.”

Gustaf was satisfied with this reasoning, and while Elin still thought it was a mean thing to do to their young sons, she said nothing. Theirs was a mixed-race marriage—between a Norwegian and a Dane—and thus all things culturally important to one but not the other were given a free pass and critiqued only in unmixed company.

• • •

Yearly intimate contact with their cultural heritage failed to evolve the Thorvald boys’ sensibilities. Jarl, who still ate his own snot, much preferred the taste of boogers to lutefisk, given that the consistency and color were the same. Lars, meanwhile, was stumped by the old Scandinavian

women who walked up to him in church and said, “Any young man who makes lutefisk like you do is going to be quite popular with the ladies.” In Lars’s experience, lutefisk skills usually inspired revulsion or, at best, indifference among prospective dates. Even the girls who claimed they liked lutefisk didn’t want to smell it when they weren’t eating it, and Lars couldn’t give them much of a choice. The once-anticipated holiday season had become for Lars a cruel month of stench and rejection, and thanks to the boys at school, its social effects lingered long after everyone’s desiccated Christmas trees were abandoned by the curbside.

• • •

By the time Lars was eighteen, whatever tolerance he’d once had for this uncompromising tradition had long eroded. His hands were scarred from several Advents of soaking dried whitefish in lye, and every year the smell clung harder to his pores, fingernails, hair, and shoes, and not just because their surface areas had increased with maturity. Lars had also grown to become a little wizard in the kitchen, and by his unintentionally mastering the tragic hobby of lutefisk preparation, its potency was skyrocketing. Lutherans were driving from as far away as Fergus Falls to try the “Thorvald lutefisk,” and there wasn’t an attractive young woman among any of them.

As if to mock him further every year, Lars’s dad would shove a forkful of the crap in his face each Christmas.

“Just a bite,” Gustaf would say. “Your ancestors ate this to survive the long winters.”

“And how did they survive lutefisk?” Lars asked once.

“Take some pride in your work, son,” Gustaf said, and took away his lefse in punishment.

• • •

In 1978, Lars graduated from high school and got the heck out of Duluth. His grades could’ve gotten him into a nice Lutheran school like

Gustavus Adolphus or Augsburg, but Lars wanted to be a chef, and he didn’t see what good college would do him other than to delay that goal by four years. Instead he moved down to the Cities, looking for a girlfriend and for kitchen work in whatever order, requiring only that no one insist he make lutefisk. That attitude sure left a lot more options open than his father had predicted.

After a ten-year unpaid apprenticeship at Gustaf & Sons, Lars was already skilled at baking—arguably the most difficult of all culinary duties—but didn’t want to fall back on that. Because he only chose jobs that could teach him something, and went on dates about as often as a vegetarian restaurant opened near an interstate highway, he gained a pretty decent handle on French, Italian, German, and American cuisine in just under a decade.

By October 1987, as his home state was enraptured by the Twins winning their first World Series ever, Lars had earned a job as a chef at Hutmacher’s, a trendy lakeside restaurant that attracted big celebrities, like meteorologists, state senators, and local pro athletes. For years, it was said, a Twins player could enjoy his meals at Hutmacher’s unremarked and unmolested, but by the week Lars was hired, jubilant ballplayers were regularly turning the late shift into an upbeat party.

Amid the circumstance of a long-suffering sports team’s success, the strange joy of it all spread through the restaurant. It was during these happy weeks when Cynthia Hargreaves, the smartest waitress on staff—she gave the best wine pairing advice of any of the servers—seemed to take an interest in Lars. By this time, he was twenty-eight, growing a pale hairy inner tube around his waist, and already going bald. Even though she had an overbite and the shakes, she was six feet tall and beautiful, and not like a statue or a perfume advertisement, but in a realistic way, like how a truck or a pizza is beautiful at the moment you want it most. This, to Lars, made her feel approachable.

When she came back to the kitchen, the guys would all openly check her out, but Lars refrained. Instead, he’d look her in the face while he

told her things like, “Tell them it’ll be five more minutes on that veal,” and “No, I will not hold the garlic—it’s pesto.”

“Oh, you can’t make a sauce with just pine nuts, olive oil, basil, and Romano?” she asked.

He was a bit impressed that she knew the other ingredients off the top of her head. Maybe he shouldn’t have been, but it just wasn’t the kind of thing he expected people outside a kitchen to know. He knew he must have communicated this to her when he saw how she was smiling back at him knowingly, like he had been caught in the act of something.

“Well, you know, I can try,” he said. “But then it’s not pesto, it’s something else.”

“How fresh is the basil?” she asked. “Pesto lives or dies by its basil.”

He admired her decisive way of phrasing that incorrect opinion. It was actually the preparation that determined its quality; proper pesto, he had learned during a previous job at Pronto Ristorante, is made with a mortar and pestle. It makes all the difference.

“It’s two days old,” he said.

“Where’d you get it from? St. Paul Farmers’ Market?”

“Yeah, from Anna Hlavek.”

“Oh, you should get it from Ellen Chamberlain. Ellen grows the best basil.”

Such wonderfully erroneous food opinions! This was getting Lars all riled up. Still, in his Minneapolis years, liberated from both his lutefisk stench and its reputation, he’d driven women away due to what they called his “eagerness,” and he couldn’t allow that to happen again.

“Oh, she does, now?” he asked her, continuing to work, not looking up at her.

“Yeah,” she said, stepping closer to him, trying to keep him engaged. “Anna grows sweet corn in the same plot as her basil. You know what sweet corn does to soil.”

She had a point, if that were true. “I didn’t know Anna grew sweet corn.”

“She doesn’t sell it to the public.” She smiled at him again. “And I’ll tell my customer yes on the garlic-free pesto, anyway.”

“Why?”

“I want to see you work a little harder back here,” she said.

He couldn’t help it—he was in love by the time she left the kitchen—but love made him feel sad and doomed, as usual. What he didn’t know was that she’d suffered through a decade of cool, commitment-phobic men, and Lars’s kindness, but mostly his effusive, overt enthusiasm for her, was at that time exactly what she wanted in a partner.

• • •

Cynthia was pregnant, but not showing, by the time they were married in late October 1988. Lars was still a chef at Hutmacher’s, and she was still their most popular waitress, but despite the storybook romance that had flourished within their establishment, the owners refused to shut the restaurant down on a Saturday to host the wedding reception.

Lars’s father, still infuriated that his eldest son had abandoned both the family bakery and the responsibility of supplying lutefisk for thousands of intransigent Scandinavians, boycotted the wedding and refused to support any aspect of it. If Lars was having his mother’s first grandchild, she might have been inspired to help, but instead Elin was already busy with Sigmund’s two kids; naturally, the one brother who’d never made lutefisk in his life had lost his virginity, and fruitfully, by age seventeen.

• • •

The couple honeymooned in the Napa Valley, which was still flush from the shocking Judgment of Paris more than a decade earlier and happily maturing into its new volume of wine tourism. Lars had never experienced a wine tasting before, and while her new husband threw back the one-ounce pours, Cynthia consumed everything on the labels, the

vineyard tours, and the maps. It was her first trip to California, and even completely sober, her body swooned at the sight of a grapevine and her soul flourished in the jungle of argot:

varietal, Brix, rootstock, malolactic fermentation

. In the rental car, with his eyes closed while trying to sleep off a surfeit of heavy afternoon reds, Lars could feel her smiling as she drove him and their unborn child through the shimmering California hills.

“I love this so much,” she said.

“I love you, too,” he said, though that was not what she meant.

• • •

They’d agreed, if it was a boy, that Lars would name the baby, and if it was a girl, Cynthia would. Eva Louise Thorvald was born two weeks before her due date, on June 2, 1989, coming into the world at an assertive ten pounds, two ounces. When Lars first held her, his heart melted over her like butter on warm bread, and he would never get it back. When mother and baby were asleep in the hospital room, he went out to the parking lot, sat in his Dodge Omni, and cried like a man who had never wanted anything in his life until now.

• • •

“Let’s give it five or six years before we have another one,” Cynthia said, and got herself an IUD. Lars had been hoping for at least three kids, like in his own family, but he supposed there was time. He tried to impress upon Cynthia the fact that having multiple kids means at least one of them will stick around to make sure that you don’t die alone if you fall in the shower or trip on your basement staircase. He pointed out how after he and Jarl had gotten out of Duluth, their middle brother, Sigmund, had taken over both the bakery and the extraordinary demands of their dying parents, and how that was working out super for everybody. This line of argument was not compelling to his twenty-five-year-old wife. Cynthia wanted to get into wine.

• • •

In the same fashion that a musical parent may curate their child’s exposure to certain songs, Lars had spent weeks plotting a menu for his baby daughter’s first months:

Week One

NO TEETH, SO:

1. Homemade guacamole.

2. Puréed prunes (do infants like prunes?)

3. Puréed carrots (Sugarsnax 54, ideally, but more likely Autumn King).

4. Puréed beets (Lutz green leaf).

5. Homemade Honeycrisp applesauce (get apples from Dennis Wu).

6. Hummus (from canned chickpeas? Maybe wait for week 2.)

7. Olive tapenade (maybe with puréed Cerignola olives? Ask Sherry Dubcek about the best kind of olives for a newborn.)