Knights of the Hawk

Contents

About the Book

AUTUMN, 1071. The struggle for England has been long and brutal. Now, however, five years after the fateful Battle of Hastings, only a determined band of rebels in the Fens stands between King William and absolute conquest.

Tancred, a proud and ambitious knight, is among the Normans marching to crush them. Once lauded for his exploits, his fame is now fading. Embittered by his dwindling fortunes and by the oath shackling him to his lord, he yearns for the chance to win back his reputation through the spilling of enemy blood.

But as the Normans’ attempts to assault the rebels’ island stronghold meet with failure, the King grows increasingly desperate. With morale in camp failing, and the prospect of victory seeming ever more distant, Tancred’s loyalty is put to the test as never before.

As friendships sour and old grudges resurface, Tancred must make a choice that will determine his destiny. Together with a host of unlikely allies, he sets out on a journey that will take him from the marshes of East Anglia into the wild, storm-tossed seas of the north, as he ventures in pursuit of love, of honour, and of vengeance.

About the Author

James Aitcheson was born in Wiltshire and read History at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where began his fascination with the medieval period and the Norman Conquest in particular.

Knights of the Hawk

is his third novel.

Also by James Aitcheson

Sworn Sword

The Splintered Kingdom

Knights of the Hawk

JAMES AITCHESON

For Alistair

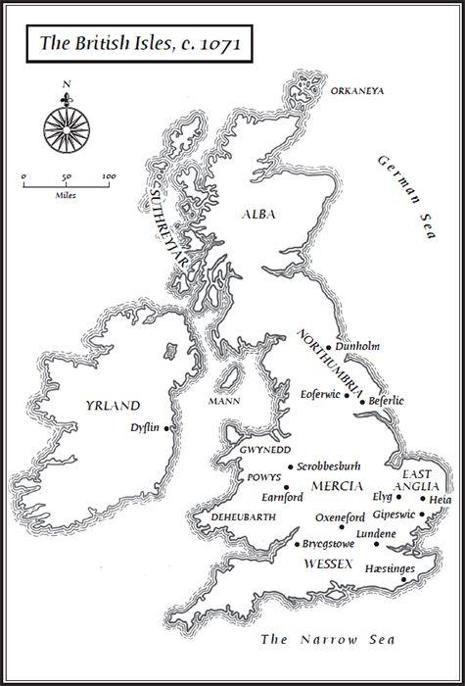

List of Place-Names

THROUGHOUT THE NOVEL

I have chosen to use contemporary names for the locations involved, as recorded in charters, chronicles and in Domesday Book (1086). Spellings of these names were rarely consistent, however, and often many variations were current at the same time, as for example for Cambridge, which in this period was rendered as Grantanbrycge, Grantabricge and Grentebrige in addition to the form that I have preferred, Cantebrigia. For locations within the British Isles my principal sources have been

A Dictionary of British Place-Names

, edited by A. D. Mills (OUP: Oxford, 2003) and

The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names

, edited by Victor Watts (CUP: Cambridge, 2004).

Alba | Scotland |

Alrehetha | Aldreth, Cambridgeshire |

Archis | Arques-la-Bataille, France |

Beferlic | Beverley, East Riding of Yorkshire |

Brandune | Brandon, Suffolk |

Brycgstowe | Bristol |

Burh | Peterborough, Cambridgeshire |

Cadum | Caen, France |

Cantebrigia | Cambridge |

Ceastre | Chester |

Clune | Clun, Shropshire |

Commines | Comines, France/Belgium |

Corbei | Corby, Northamptonshire |

Cornualia | Cornwall |

Defnascir | Devon |

Dinant | Dinan, France |

Dunholm | Durham |

Dure | Jura, Argyll and Bute |

Dyflin | Dublin, Republic of Ireland |

Earnford | near Bucknell, Shropshire (fictional) |

Elyg | Ely, Cambridgeshire |

Eoferwic | York |

Gipeswic | Ipswich, Suffolk |

Glowecestre | Gloucester |

Hæstinges | Hastings, East Sussex |

Haltland | Shetland |

Heia | Eye, Suffolk |

Hlymrekr | Limerick, Republic of Ireland |

Ile | Islay, Argyll and Bute |

Kathenessia | Caithness |

Leomynstre | Leominster, Herefordshire |

Litelport | Littleport, Cambridgeshire |

Lundene | London |

Lyteluse | River Little Ouse |

Mann | Isle of Man |

Montgommeri | Sainte-Foy-de-Montgommery, France |

Orkaneya | Orkney |

Oxeneford | Oxford |

Rencesvals | Roncesvalles, Spain |

Sarraguce | Zaragoza, Spain |

Saverna | River Severn |

Scrobbesburh | Shrewsbury, Shropshire |

Sudwerca | Southwark, Greater London |

Suthreyjar | Hebrides |

Temes | River Thames |

Use | River Great Ouse |

Utwell | Outwell, Norfolk |

Wiceford | Witchford, Cambridgeshire |

Wiltune | Wilton, Wiltshire |

Wirecestre | Worcester |

Yrland | Ireland |

Ysland | Iceland |

Prologue

A MAN ALWAYS

remembers his first kill. In the same way that he can recall the time he first felt a woman’s touch, so he can conjure up the face of his first victim and every detail of that moment. Even many years later he will be able to say where it took place and what was the time of day, whether it was raining or whether the sun shone, how he held his blade and how he struck and where he buried the steel. He will remember his foe’s screams ringing in his ears, the feel of warm blood running across his fingers and the stench of voided bowels and freshly opened guts rising up. He will remember the horror brought on by the realisation of what he has done, of what he has become, and those memories will remain with him as long as he lives.

And so it was with me. Rarely have I ever spoken of this, and even among my closest companions there are few who know the whole story. There was a time years ago when my fellow knights and I would spend the evenings sitting around the campfire and spinning boastful yarns of our achievements, but even then it was never something I cared to speak of, and I would often change the details to suit what I thought those listening would prefer to hear. Why that was, I’m unsure. Perhaps it is because it didn’t happen in the heat and thunder of the charge, or in the grim spearwork of the shield-wall, as many might wish to think, and for that reason I am ashamed, although many of my fellow warriors would undoubtedly have a similar story to tell. Perhaps it is because all these events that I now set down in writing took place many decades ago, and when I look back on my time upon this earth there are far nobler deeds that I would rather remember. Perhaps it is simply because it is no one’s business but my own.

What happened is this. I was in my sixteenth summer at the time: more than a boy but not quite a man; a promising rider but not yet proficient in swordcraft, and still lacking in the virtues of patience and temper that were required of the oath-sworn knight I aspired to be. Like all youths I was hot-tempered and arrogant; my head was filled with dreams of glory and plunder and a foolish belief that nothing in the world could harm me, and it was that same foolishness that caused me to cross those men that summer’s day.

We had that afternoon arrived in some small Flemish river-town, the name of which I’ve long since forgotten, on our way home from paying homage to the Norman duke. I had been sent with a purse full of silver by the man who was then my lord, Robert de Commines, to secure overnight lodgings for our party. It should have been an easy task, except that it happened to be a market day, and not only that but it was also nearing the feast of a minor saint whose name I was unfamiliar with but whom the folk of the surrounding country revered, which meant that the streets were crowded and each one of the dozen inns I visited was already full with merchants and pilgrims who had come to sell their wares, to worship and to attend the festivities.

Weary from my wanderings, eventually I found a corner of the main thoroughfare where I could sit upon the dusty ground and rest my legs. Leaning back against a wall, I wondered whether it was better to return to Lord Robert, tell him of my failure and risk his displeasure, or to keep looking, though it seemed a fruitless task. My throat was parched and I drank down the last few drops from my ale-flask to soothe it. The pungent fragrance of the spice-monger’s garlic filled my nose, mixed with the less palatable smells of cattle dung from the streets and the carcasses of poultry hanging from the butchers’ stalls. Once in a while my ears would make out a few words in French or Breton, the only two worldly tongues I was familiar with, but otherwise all I heard was a cacophony of men and women calling across the wide marketplace, dogs barking, young children shrieking as they chased each other in between the stalls, prompting annoyed shouts from those whose paths they obstructed. Oxen snorted as they drew wagons laden with sheaves of wheat and casks that might have contained wine, or else some kind of salted meat. A young man juggled coloured balls and some of the townsfolk crowded around to marvel at his skill; from one of the side streets floated the sound of a pipe, accompanied by the steady beating of a tabor.

And then I saw her. She sat on a stool on the other side of the wide street, behind a trestle table laden with wet-glistening salmon and herring. Her fair hair was uncovered, tied in a loose braid that shone gold in the sun and trailed halfway down her back, a sign that she wasn’t yet wed. By my reckoning she was about as old as myself, or perhaps a year or so older; I have never been much good at guessing ages. She had a fine-featured face, with attentive, smiling eyes, and a friendly manner with the folk who stopped at the stall to ask how much those fish were worth and to argue the price, before grudgingly and at length handing over their coin.