Las Christmas (17 page)

“Maybe it was not all wasted,” my mother was giggling and I was, too, by then. “I think it may have seeped into your brain through your pores.”

While I listened to my mother and my uncle talk, I saw how all their daily struggles ceased for the time it took to tell the

cuento,

how pleased they were with their own wit, their ability to laugh at disappointments and hurts, and best of all, to transform any ordinary episode into an adventure.

ON CHRISTMAS EVE the family gathered in our living room. My mother and I had polished the green linoleum floor until it was a mirror reflecting the multicolored lights of the Christmas tree which had done its job of perfuming our apartment with the aroma of evergreen. I was wearing a red party dress my mother had let me choose from her closet and a pair of her pumps. I looked at least eighteen, I thought. I put some of TÃo's

pachanga

records on our turntable and waited anxiously for him to come through the door with my gift. What I expected it to be was in the airy realm of a dream. But it would, I knew without a doubt, be magical.

It was late when he finally showed up bearing a brown grocery bag full of gifts, a bleached-blond woman on his arm. After kissing his sisters, waving to me from across the room, and wishing everyone

Felices Pascuas,

he and his partner left for another party. My mother and aunts shook their heads at their brother's latest caprice. My feet hurt in the high-heeled shoes, so I sat out the dances and read one of my mother's books. Some time around midnight I was handed my gifts. Among them there was an unwrapped box of perfume with a card from my uncle. The perfume was Tabu. The card read: “

La

Cenisosa

from our Island does not get a prince as a reward. She has another gift given to her. I heard a woman tell this

cuento

once. Maybe you can find it in the library or ask Mamá to tell it to you when you visit her next time.”

My mother thought the perfume was too strong for a girl my age and would not let me wear it. I was disappointed by the gift, but I would occasionally spray on the perfume anyway. I discovered that its wilted flower scent triggered my imagination. I could imagine myself in many different ways when I smelled it. It was the kind of perfume no one else would ever give me again.

I did not find the

cuento

of

La Cenisosa

in the Paterson Public Library, nor in any other book collection for many years. Recently I ran across an anthology of

cuentos folklóricos

from Puerto Rico, and there it was:

La Cenisosa.

In

La

Cenisosa

of Puerto Rico, Cinderella is rewarded by a family of three

hadas

madrinas,

fairy godmothers, for her generosity of spirit, but her prize is not the hand of a prince. Instead, she is rewarded with diamonds and pearls that fall from her mouth whenever she opens it to speak. And she finds that she can be brave enough to stand up to her wicked stepmother and stepsisters and clever enough to banish them from her home forever. Around the time when I translated this folktale my mother wrote to say that my uncle was dying from cancer of the throat back on the Island where they had both returned years ago. She said that his voice was almost totally gone but not his indomitable spirit. He knew he had little time left to give us the words he wanted us to remember. He had my mother write to me and tell me that he had read my novel and wanted me to know that my stories gave him pleasure. He sent me his

bendición.

I took his blessing to mean that he had accepted my gift of words.

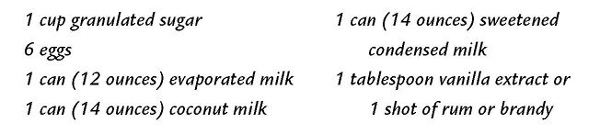

Coconut Flan

This recipe comes to us from Ada T. Rosaly of Ponce, Puerto Rico, the mother of our dear friend, Eileen Rosaly. When Ada visits her daughter in Los Angeles, she is always called upon to bake a flan, which disappears in minutes. Her recipe is virtually foolproof, so even if you've never tried to make flan before, you will be able to impress your friends with this one. The ingredients are not exactly low in cholesterol, but trust us, it's worth every calorie.

To caramelize the pan

Pour the sugar into a square or round flan mold or cake pan about 9 inches in diameter and 3 to 4 inches deep, and cook over low heat, agitating constantly to prevent scorching. When the sugar begins to bubble, remove the pan from the heat and turn it so the caramel glaze covers the bottom of the mold evenly. Set aside to cool.

To prepare the custard

Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

Lightly beat the eggs, then continue to beat the mixture as the remaining ingredients are added. Beat until well blended. Pour the mixture through a strainer into the prepared mold.

Place the mold into a larger pan filled with ½ to 1 inch of hot water, so that the water comes about half way up the side of the mold. Bake 45 to 50 minutes or until a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean.

Remove from the oven and allow the mold to cool on a rack. To unmold, dip the mold in warm water before inverting it onto a serving platter.

Makes

8

to

10

servings

Luis J. RodrÃguez

Luis J. RodrÃguez grew up in South Central and East L.A. He is the author of the award-winning memoir Always Running: La Vida Loca, Gang Days in L.A.,

as well as several volumes of poetry. He has been the recipient of a Lila Wallaceâ

Readers' Digest Writer's Award and a Lannan Fellowship. He is also the publisher

of TÃa Chucha Press, a Chicago-based publishing company specializing in poetry.

COLORS BREATHING THEMSELVES INTO THE BODY

For Diego RodrÃguez

SOUNDS OF TrÃo los Panchos or AugustÃn Lara rustled through the wood-paneled room. Christmas at Diego's house glistened with pine needles on a tree, flickering lights on all the branches, and multicolored gift-wrapped boxes heaped in a corner. What I knew about holidays, I had learned from Diego, my half-sister Seni's husband. He was the energy igniting every room, the center of every festivity, the court jester of Los RodrÃguez.

Diego was a second father, the other man to guide us. He made sure the children visited parks, took in a drive-in movie, or had a night out at a local diner. When all was gloom, he was light. When all was cruel, he was kind. I don't ever remember Diego angry; he was perplexing sometimes and toughâ never angry.

First the cells mutate into a constellation of malignant stars, dividing and

replicating, corrupting and influencingâa malfeasance of genes that industry,smog, cigarettes, and chemical-laden foods have blessed us with, palpitatingbeneath the tissues, birthing and killing at once, like colors breathing

themselves into the body.

For a brief period, our family was homeless. It was after the bank foreclosed on our house in Reseda, where we lived for a year as one of the first Mexican families in that part of the San Fernando Valley. My father had lost his job, gone bankrupt, and everything had been taken away. The family returned to South Central L.A., the area of Los Angeles where we first landed after leaving Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, when I was two years old. There were no homeless shelters for families in those days. We slept in the living rooms of

comadres

and friends, taking turns going from one household to another; never in one place for more than a few nights. At one point, my mother was determined to take her children back to Mexicoâwithout my father, if necessaryârather than stay in L.A. with nothing to our name. We made it as far as the inside of Union Station before she changed her mind, her face drenched in tears.

After that, we moved in with Seni, sharing her small two-bedroom apartment in Monterey Park with Diego and their two young daughters. There were eleven of us there at one time, including Seni's family, my grandmother Catita, my parents, and their four children. The children slept on blankets strewn about the living room. There were good times. But there were terrible times. Constant arguing; storming out of rooms, banging of doors. My brother Rano and I crept out of the house into the streets. I was about eight years old. A child could easily disappear between the shouts.

One night, Rano and I came home after dark. There were police cars parked outside our building. Neighbors stood on the lawn and driveway. We went inside to find my nieces and sisters crying. There was blood on a wall. A burly policeman was taking notes. Seni, following a particularly heated argument, had stabbed Diego with a nail file. He was okay. In fact, he decided this was a good time to take the kids to the park while the rest of the family calmed down. So we went along, Diego's arm heavily wrapped in gauze.

We lasted about a year there. Diego tried to keep Christmas alive, even when there were no toys to pass around. Somehow, we weathered all the turmoil. One Christmas, our family received a big bag of groceries, including a turkey, and an allotment of toys from a Catholic charity. Each child had at least one toy to call their own. I was so excited, I broke the little plastic submarine the first day.

On L.A.'s East Side, families were spread out beneath the smog blanket ensnared by the San Gabriel Mountains. The deadly exhalation of every car in the city lingered there. Winds carried the venom, creeping through back windows and air vents. Corridors of industryâthe smelters, the rolling mills, the packing sheds, the refineries, the assembly linesâpropelled the brown halo across this Valley of Death, which was known for gang violence, but it might as well have been known for the “industry drive-bys” that claimed even more lives.

Cancer, long linked to this polluted environment, struck home. My father died of stomach cancer in 1992. My sister Gloria's daughter had a form of bone cancer. Gloria was diagnosed with lupus and other related ailments. And Diego got hit particularly hard.

The L.A. basin had one of the largest concentrations of industry after the Rhineland. Only Chicago had more. When you think of L.A., don't just think about Mickey Mouse or Melrose Avenue or Muscle Beach; think, too, of the other side of town, of blast furnaces, bucket shops, the odorous funk of Farmer John's slaughterhouse. Think of cancer growing like prickly cactus in a desert. Think of Diego.

THE AIR WHISTLES JAZZED each morning to the worm-worm belly of refineries and factories that consumed generations of

familias

from Michoacán, Guerrero, Durango, Chihuahua, Sinaloa.

Diego began at the paint factory as a gofer. Everyone liked Diego. He made jokes in a terribly accented English, but he spoke with a confidence that sometimes clarified better than words. He eventually learned English, but for years it was a word or two at a time. There was a period when he called everyone “Sugar.” Cigarette ash followed him everywhere he walked.

He worked better, smarter, and with greater grace than anyone around. Soon he moved up into positions at the plant where brown skin and strange idioms normally found no home; but Diego, his brashness not a tactic but an authentic song, kept bettering his betters. He learned the chemical composition of paint, how it could change before the eyes, how light falls into a place of colorlessness and allows an inner shade to glow. After a few years, Diego became mixer and creator, the man behind new and complex tones that soon graced the rooms of children and the dens of other working men with a hybridity of hues that danced inside his bones like neon.

ONE CHRISTMAS, when I was about twelve years old, Diego brought out my first new bike. My parents had bought it for me. It had been hidden in the closet; I never suspected a thing. The bike was a shiny blue Stingray with a black leather banana seat.

¡De aquellas, ese!

The coolest thing. For a long time, I had envied other kids their low-riding cycles. But we never seemed to have any money. I had started a paper route and was using a beat-up ten-speed that I had found somewhere and fixed. For once, I had me a new bike!

That night, I parked the bike next to my bed. I stayed up all night just looking at it. I couldn't sleep. The light of the moon through the window struck the bike at all the right angles. It sparkled and shone. Maybe it was my imagination. I don't recall when I finally passed out, but as soon as morning broke, I was up and riding my bike.

I rode it to a friend's house, where I gently placed it on the lawn. I showed it off, then we went inside the house briefly. When I came back, the bike was gone. Stolen! I couldn't believe it. I ran down the street, looking in yards, down alleys and up and down streets. But it was nowhere to be found. My beautiful bike. Gone.

I didn't know how to face my parents or Diego. I never saw that bike again. I never got another one. I kept on using my old ten-speed to deliver newspapers. But I never forgot that bike. I never forgot how important it made me feel, how solid in the world. I never forgot someone had made the effort to give my life such brilliance, even for too short a while, a brilliance that took me through dark times.

TUMORS ERUPTED all over Diego's body. There were lumps on his throat, head, and hands; the chemotherapy had destroyed his hair; he looked bloated. All the toxins, tints, smells, shades, and smoke had transmuted, developing and feeding on themselves. No sci-fi flick could even come close. For one last time, Diego sat around with the rest of the family, watching the 8-mm films he had made over a span of thirty years: birthdays, Christmases, visits to the beach, to amusement parks, to Mexico. I was thirty-eight years old; Diego was fifty-four. Till the very end, Diego joked, doing the Cantinflas shuffle through the difficult hours of his days. Even in my most confusing moments, Diego never put me down; he always found something to tease me about.

A few years before he died, long after I had left East L.A. and moved to Chicago, Diego arrived in town for a convention of paint chemists. Holed up at a fancy Hilton downtown, he said he felt out of place. There was a Taco Loco down the street in a dingy section of the Loop. Diego called to see if I could come by and visit with him. But not at the Hilton.

“Meet me at the Taco Loco,” he said.

When I got there, a homeless man lay across the sidewalk, a wino asked for change, and Mexican hotel workers waited at a bus stop. Diego, meanwhile, was midway into a taco, his coat and tie removed, his white shirt opened at the neck, and mounds of salsa spilling over his plate. It was the last time I saw him looking healthy.

THEY BURIED Diego in a vase of ashes. On the day of the funeral his young granddaughter got upset when the funeral-home workers patted the earth with a shovel.

“Don't bury my granddaddy!” she yelled.

The owner of the paint factory attended the services, emerging from a limousine. Some complained he had no right to be there. Others said the guy truly appreciated Diego. Remembering Diego, they all could have been right.

Diego had a way of obliterating all the grays with laughter, songs, and home movies. I haven't had a Christmas yet without remembering how he called out the name on each present, how he passed them out to eager, empty handsâwhen Christmas was not so much about things but about remarkable people and the gifts they shared.