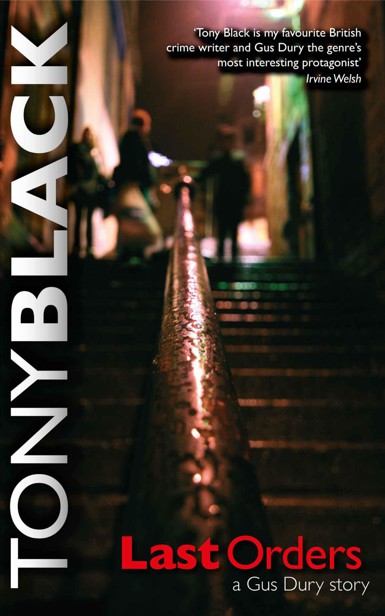

Last Orders (a Gus Dury crime thriller)

Read Last Orders (a Gus Dury crime thriller) Online

Authors: Tony Black

An original Gus Dury story by Tony Black

Copyright © Tony Black 2013

Tony Black has asserted his right to be identified as

the author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it

shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be hired, resold, lent out, or in any

way circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding,

cover or electronic format other than that in which it is published and without

a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on any subsequent

purchaser.

First published in Scotland in 2013 by Pusher Press.

All similarities to actual characters — living or dead

— is purely coincidental.

Cover image & design: Jim Divine

www.tonyblack.net

LAST ORDERS

When he receives a mysterious letter on expensively

embossed paper, reluctant investigator Gus Dury decides to take the case, if

for no other reason than he needs the cash. But there's something about his

well-heeled client, Callum Urquhart, that doesn't sit right with Dury.

Urquhart has travelled across the country to find his

missing teenage daughter — who definitely doesn't want to be found. As Dury

gets closer to locating Caroline, what he uncovers is a web of lies and deceit

and some painful realisations that lead back to his own tangled past.

Last Orders

is a 14,000 word novella from the

author of the Random House UK Gus Dury series:

Paying for It

,

Gutted

,

Loss

, and

Long Time Dead

.

Praise for the Gus Dury

series by Tony Black:

'Tony Black is the latest of the seemingly unending

stream of good Scottish crime writers who have in common the ability to portray

vividly the underbelly of Scottish inner-city criminality ... The dialogue

fizzes and the whole is suffused with black humour'

-The Times

'Tony Black's first novel hits the ground running,

combining a sympathetic ear for the surreal dialogue of the dispossessed with a

portrait of the belly of a city painted in the blackest of humour'

-The Guardian

'If you're a fan of the Ian Rankins, Denise Minas

and Irvine Welshes of this world, this is most certainly one for you'

-The Scotsman

'The enigmatic Dury continues to be the punk rocker

of the Scottish crime scene — anarchic, rebellious and never afraid to shove

his Doc Martens where they're not wanted'

-Daily Record

'As washed-up private detectives go, Gus Dury is

compelling — he's as hard as any criminal and twice as self-destructive'

-London Evening

Standard

'Ripping, gutsy prose and a witty wreck of a

protagonist makes this another exceptionally compelling, bright and even

original thriller'

-Daily Mirror

'Tony Black is my favourite British crime writer and

Gus Dury the genre's most interesting protagonist. Like his previous books,

Loss has the power, style and street swagger that makes most of his

contemporaries a little bland by comparison'

-Irvine Welsh,

author of

Trainspotting

'Tony Black has written two of the finest crime

novels to come out of the UK in the past twenty years and I'm willing to bet

that in twenty years,

Paying for It

and

Gutted

will be in the top

ten of any crime list. But now comes

Loss

... Phew-oh ... It's like

having yer ass kicked and yer heart shrived simultaneously. What a privilege to

watch a master writer achieve everything you'd hoped for and then some'

-Ken Bruen, author

of

London Boulevard

'Powerful, focused, and intense ... and then it gets

better. Get your money down early on this young man — he's dead serious and

deadly accurate'

-Andrew Vachss,

author of

Hard Candy

Last Orders

a Gus Dury story

by Tony Black

'We spend our lives in flight from all that is

painful and real.'

-Paul Sayer,

The God Child

I thought I'd seen it all. Maybe that's why I couldn't

bring myself to open my eyes. I was lying in bed at my Easter Road flat-cum-kip

house when I heard the postie rattle the slot and drop some mail onto the mat

below. I had a thought to test one eye on the clock but then routine, the old

leveller, kicked in. The days of posties showing before 2 p.m. in this city

were well over so the only question kicking me out of bed during daylight hours

was who the fuck could be interested in writing to me?

I shifted onto my side, provoked an ear-splitting cough

that sent knives stabbing at my lower back. My first thought was to reach for a

smoke, but I could see the soft-pack of Marlboros crumpled on the floor by the

scuffed foot of the dresser. I was all out of luck again.

It was cold. I felt the chill from the loose,

condensation-wet windowpanes on my bare shoulders. A shiver passed through me —

my mother would have said someone was walking over my grave and the way my

chest felt I wouldn't have argued the toss; I could already be in it.

I was rubbing the outside of my arms, trying to suggest

some warmth into my pasty-white Scottish limbs as I caught sight of a mirror to

mirror reflection. My heart started as I imagined the image was of someone else

in the room with me. When sense returned I realised the door to the wardrobe

had my back on display as I clocked myself in the dresser mirror. I was shocked

by how prominent the gnarled length of my spine looked, sticking out at sharp

angles, like a bust bike-chain lying twisted in the gutter. I turned and took

in the toast-rack chest and the full hit of high-ribs exposed like tiger's

stripes down my sides.

'Jesus, Dury ...' I mouthed towards the gaunt, coughing

cadaver in front of me. 'I've seen more fat on a chip.'

I reached for the Wranglers hanging on the chair's back

and slotted myself into them. They felt loose, the old leather belt settling on

the last notch. I couldn't face the prospect of catching another glimpse of

myself, so covered up fast with an old Nike hoodie and headed for the door.

There had been a time, back in the day, when I had a dog

that would have been wagging his tail at the sight of me. The thought of the

rescue dog I'd christened

Usual

— a name he picked up at the pub — dug

at my heart. My ex-wife had claimed him; said I wasn't fit to look after

myself, never mind an animal. I couldn't argue with that.

There were two letters on the mat. I opted first for the

manila oblong that spelled business-post, or worse, a bill. I liked to get bad

news out the way. I ripped into the top and tore out the white letter; an NHS

logo was the first thing to grip me. It wasn't a demand for cash, I was relieved

at that, but I could afford this demand less:

'Blah, blah ...' I read, 'requests your attendance at

the Hypertension Clinic.'

My blood pressure was through the roof. The result of a

damaged liver and a scarred heart. Apparently, the letter stated, I needed

bi-monthly checks at the clinic to make sure I wasn't going to cark it.

'Christ, no ...'

I scrunched the paper in my hand. If there was one thing

in the world I couldn't handle it was hospitals. I had too many bad memories of

seeing the ones I had loved there; and they weren't out-weighed by the good

memories of seeing the ones I definitely didn't love going there, usually at

speed.

I threw the ball of the letter at the wall, it bounced

back and rolled its way down the carpet towards the bedroom.

'Fucking Hypertension Clinic ...'

The second missive was a mystery. It was the same shape

as the first, but a long white envelope this time. I checked the franking over

the stamp and recognised it came from East Ayrshire.

'Burns Country ...' I was scoobied, knew not a soul

there.

I tore in. The letter inside was on cream paper, thick

and water-marked, obviously expensive. The hand looked careful, not quite

copperplate but in the ball-park.

I felt my pulse quicken as I read. Don't know why, maybe

it was something about the tone. If I had to go for a tag, I'd say:

reverential.

The opener was a

Dear Mr Dury

— couldn't say I

liked that. When I see the honorific in there, I start thinking someone's

confused me with my father. The bold Cannis Dury was no man to be confused

with.

I read on:

I hope you will forgive the impertinence of my

enquiry but your name was forwarded to me as a man who may be able to assist in

my most desperate hour ...

I rolled eyes to the ceiling. It was the

Help me

Obi-Wan, you're my only hope

line again. This was happening more and more

now. My reputation going before me. I'd been a good hack, handled some big

stories but that was behind me. How I got lumbered with the investigator for

hire rep was something I couldn't work out. Life was funny that way, though.

Man plans, God laughs.

... I will, of course, meet all necessary expenses

and you will not find me ungenerous in this regard. I shall spare you the

formality of details at this juncture and await your telephone call at my

Edinburgh Hotel.

He was staying at The Balmoral. The only place in town

that stationed a fawning, kilted, Glengarry-wearing twat on the door. 24-7 this

stereotypical shortbread-tin evacuee tugged forelock for the likes of Sean

Connery and the dour millionairess who wrote about that bloody boy wizard.

'Elegant slumming, it has to be said.'

I looked at the cream-coloured paper once more, felt

confused enough to scratch my head but resisted. I didn't know whether to be

petrified by the haughty tone or flattered by the potential Wonka ticket in my

mitt.

I drew a still breath, exhaled. The interior of the flat

was so cold I could see the white cloud escaping my lungs.

The telephone number for The Balmoral was written beside

the name — Urquhart. It didn't ring any bells, but there were a few strings of

my curiosity being tugged. I trousered the letter and made my way back to the

bedroom to get suited and booted. There couldn't be any harm in a call and it

wasn't like I was flat-out, or even had something else to do.

* * * *

I'd flung my Crombie over the back of the couch the

night before; as I retrieved it now I could see it was covered in all the dust

and crap that the hoover didn't reach. I needed a coat-brush. Fuck it, I needed

a hoover. The coat looked just the job, for a jakey; as I tied a scarf around

my neck I could already sense the stares. Ones that said 'low-life'. There was

a time I might have been rattled, cared even. Not now. I pointed my Docs in the

direction of the door and got moving.

We had some weather, the usual Edinburgh kind. If it

wasn't rain, it was the threat thereof. I looked up to the grey skies and

crossed Easter Road between the gridlocked traffic. I was headed for the

Coopers Rest pub, couldn't say it held any special attraction for me. It was a

Hibs bar through and through and, being painted green and white, didn't wear

its credentials lightly. I'd been drawn to it lately because of the actions of

a cheeky Jambo roadworker. He'd set the winning Scottish Cup scoreline — Hearts'

5-1 drubbing of Hibs — into the tarmac with a mosaic of chalk chips. I wasn't a

Hearts supporter myself but I was a big fan of chutzpah in all its guises.

A slow-blinking old bluenose was hocking up a dose of

phlegm for the pavement, directing it carefully with a hanging drip from his

drooping lower lip. I could see this taking off, like the Heart of Midlothian

on the Royal Mile. We'd have Japanese tourists filming themselves here before

long. I smiled at the irony on my way through the door.

There were one or two old soaks propping up the bar,

hardy enough old boys with tractor tracks cut in their brows. One of them had a

nose you could open a bottle with, a heavy physique that had once been

impressive but had now gone south. He was supping a pint of Tartan and tapping

the top of a pack of Berkeley Superkings that made him a metronome for the

smoking ban. I ordered up a pint.

'Guinness, please ...' My eyes flicked onto auto-pilot

and chased the line of optics all the way down to the low-flying birdie. 'And a

double Grouse chaser.'

The barman nodded, said, 'You're as well hung for a

sheep as a lamb.'

I didn't answer. The early moments upon entering a

Scottish pub are a telling time. If you give away too much, you're liable to be

engaged in chat. I was in no mood to pass the time of day about the state of

the nation and the Tories' role in robbing us all blind or what seventies

telly-star was going to be next on the sex-offenders register.

I took my drinks and headed for the corner of the bar.

The pint of dark settled a craving, greeting me like an old friend. I was

eyeing the wee goldie when I heard the hinges of the front door sing out.

A middle-aged man, tallish and heavy-set, stood in the

lee of the door and looked unsure of himself. He was wearing a wax jacket,

mustard-coloured corduroys and brogues. His type have a name for the colour:

ox-blood. I was wearing Docs, same colour, but I call them cherry. Go figure.

I put the bead on him, knew at once he was Urquhart. My

hand went up, slowly.

He nodded, then looked upward. I could tell he wanted to

bolt, turn on his heels, throw up his hands. In the days of Empire, I'd be

flogged for failing to look the part. That's when I noticed the tweed cap in

his hands. He twisted it like he was wringing the neck of a pheasant on some

country estate. Everything about him boiled my piss. I'm working class, c'mon,

it's in the contract.

He strolled over; his voice was high and full of

affectation. 'Mr Dury, I have come a long way and ...'

'Stop right there.'

His eyes ducked into his head.

'Call me Gus. I hear the mister

in there, I think

you're after money, or worse.'

He looked to the ceiling again. Huffed. Was that a tut?

I let it slide. I sensed his distaste at the way I talked, not my accent,

though that was bad enough — heavy on the Leith — what got him was what riled

teachers in school, made them say, 'The temerity!'

I motioned him to sit; the barman brought over a bottle

of mineral water that Urquhart had ordered and placed it on the table with a

few coins of change beside it.

I eyeballed him as he pocketed the money; could tell we

weren't going to get along, we were too close to polar opposites. I said, 'Your

letter didn't tell me much.'

He checked himself; two yellow tombstones bit down on

his lower lip. His pallor was grey as concrete. His reply came slowly, 'I

believe you are a man of some ... reputation.'

I allowed myself a blink. But no more. I feared if I

gave in to temptation I'd be exposed as a man laughing himself up.

He went on, 'You have, I understand, some background.'

'

Background

?' I was scoobied.

'I took the liberty of, oh what's the demotic? Checking

you out.'

The hand again. I blocked his words. I was acting out

old habits. 'And how did you manage that?'

He shifted in his seat, started to unzip the front of

his wax jacket. As he became more settled, he removed his scarf, revealing a

dog collar. Suddenly my previous question lost its relevance.

'You're Church?'

'I am, yes, Church of Scotland ... that makes a

difference?'

The short answer was, 'Yes', the easy one was, 'Should

it?'

He said: 'That would be an ecumenical matter.'

I picked up my pint again, supped, said, 'I believe you're

right. Perhaps we should skip it and get down to business.'

'Indeed.'

His full name was Callum Urquhart. A Church of Scotland

minister from the East Ayrshire town of Cumnock. The place had once been a

thriving mining town, I knew Keir Hardie had been a union organiser there once,

but that was quite some time before Thatcher got her hooks into the miners and

started to dismantle 'society'.

Urquhart seemed agitated and eager to offer an

explanation. 'I'm a little unsettled,' he said.

'How come?'

'I have what you might call, no good reason to be here.'

'Should I get my coat?'

'No. No. Please, if you'll indulge me, Mr Dury.'

I raised brows. '

Gus

.'

'Of course ... Gus.'

He played with the lid on his mineral water, Highland

Spring,

still

. Sparkling just too exciting an option. 'I have reason,

but in no way can it be described as good.' He sighed, 'I have a daughter and

she is no longer contactable through the proper channels.'

The proper channels

... he spoke of his daughter

like he was some ponytailed ad-man at a PowerPoint presentation.

He went on. 'I'm afraid, she has, erm, well ... it's

rather embarrassing, gone missing.'

Embarrassing

? Somehow, that didn't seem the right

word. A daughter gone from home was a cause for sleepless nights, not a cause

for losing face. I eyed him cautiously over my pint, gave him some more rope.

'She got herself mixed up with the wrong crowd some time

ago. My parish is a very poor community, we once had some settled prosperity

but it's long gone and I'm afraid in its wake came some rather extreme views.'

I knew pit communities had it tough, they lost their

livelihood so an old bitch could prove a point. Some got paid off, a few grand

to piss up the wall, they called them six-month millionaires. It didn't sound

like a recipe for strong community.

'Extreme?' I said.

'Well, yes ... anarchists.'

'Go on ...'

He poured out his mineral water, drank deep, he had

quite a thirst on him now. I knew the territory. 'My daughter, Caroline, she

was a very wilful child and ...'

'Whoa, back up ... was? What makes you think we're

talking past-tense here, Minister?'

He bridled, removed a handkerchief and wiped his palms. 'A

figure of speech, I have no reason to believe ... I mean, I have nothing to go

on, Gus, that is why I have come to you.'