Leaving Mundania

Authors: Lizzie Stark

Copyright © 2012 by Lizzie Stark

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-56976-605-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stark, Lizzie.

Leaving mundania : inside the transformative world of live action role-playing games / Lizzie Stark.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

Summary: “The story of adults who put on a costume, develop a persona, and interact with other characters for hours or days as part of a LARP, or Live Action Role-Playing game. A look at the hobby from its history in the pageantry of Tudor England to its use as a training tool for the US military”âProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-1-56976-605-7 (pbk.)

1. Fantasy games. 2. Role playing. 3. Shared virtual environmentsâSocial aspects. I. Title.

GV1469.6.S63 2012

793.93--dc23

2011041606

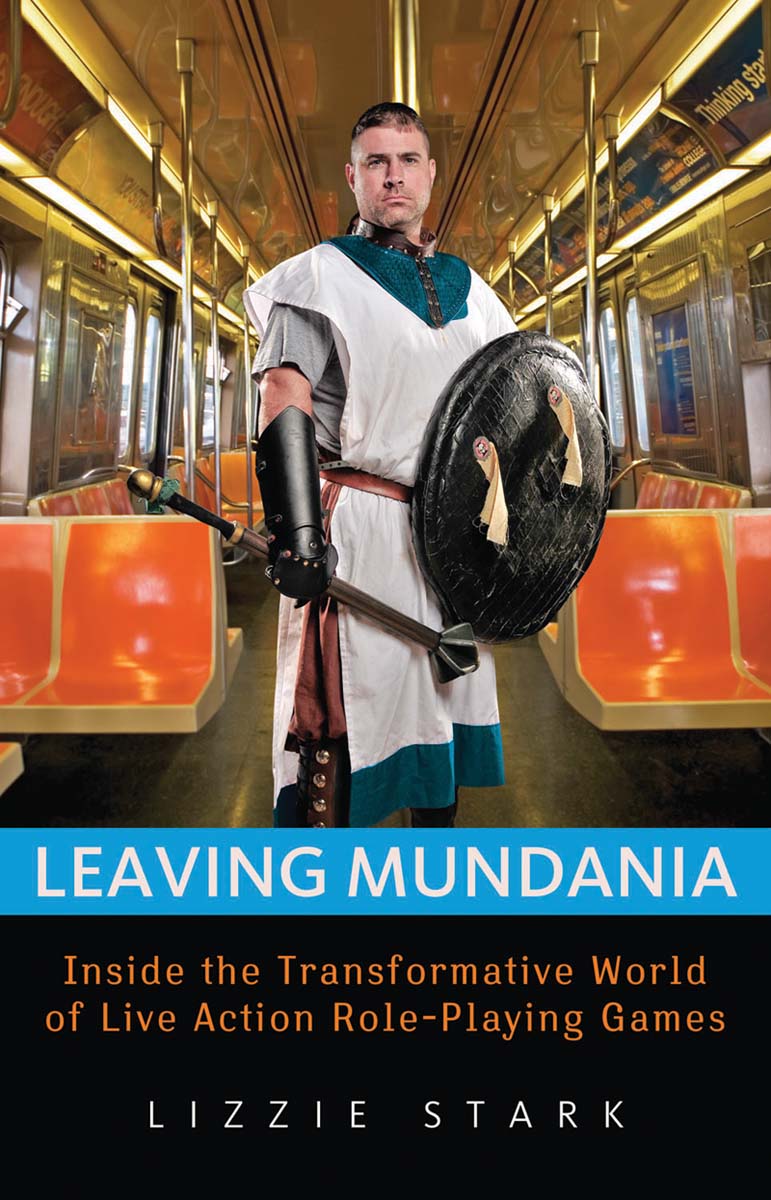

Cover design: Rebecca Lown

Cover photograph by Kyle Ober; bus image © Alloy Photography/Veer Interior design: Sarah Olson

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

For the larpers. And George.

Closeted Gamers and the Satanic Panic

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts.

âShakespeare,

As You Like It

I

n real life, they drive your trucks and make your copies. They teach your children, and repair your computers, and when you have a heart attack, they're first on the scene. They fight your wars and stock your stores and build your roads. They research new vaccines and obscure old deities. They care for your mentally ill. They train your FBI agents and catch child molesters. They are students, EMTs, lawyers, detectives, computer gurus, security guards, professional sideshow freaks, filmmakers, chefs, insurance administrators, scientists, and businessmen.

On the weekends, they are elves, magicians, cowgirls, vampires, zombies, arcane priests, samurai, druids, Jedis, zeppelin pilots, and chain-mailed warriors of unreasonable strength. They save the world. A lot. They are larpers, and they are misunderstood.

A larp, or a live action role-playing game, is similar to a theatrical play performed with no audience and no script.

*

One or more directors, called game masters, or GMs, organize everyone, select the form of the performance, and decide whether the setting resembles, for example,

Lord of the Rings, Hamlet,

or

Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Game masters have many jobs. They create plot obstacles for the player characters, challenges for the players to solve during the game. They also collect props and set the scene either by describing it verbally or by dressing the spaceâa church fellowship hall, a Boy Scout camp, a hotel roomâto look like part of the game. Sometimes the game masters write out the characters and cast them. Other times the players write their own characters. The outcome of every larp remains in question, as the characters improvise all their lines and use their wiles to solve the plots laid out for them. In all things, the game master is the final authority, the god of this little world, capable of deciding who wins the cowboy shootout in the climactic scene, if there is any dispute, and whether that found trinket is magical or merely pretty.

Just as there are many types of movies and novels, there are many styles of larp. Some larps resemble page-turning genre fiction and offer players an escapist adventure, while other larps seem more akin to literary fiction, helping players explore particular emotions, such as jealousy or love. The setting of a larp is only limited by one's imagination. There are medieval fantasy larps, Wild West larps, vampire larps, cyberpunk and steampunk larps, and larps that take place in particular historical periods. Some games involve fantastical elements such as magic or vampires, while other games are firmly rooted in the rules of reality. A game may last a few hours, a weekend, or, in rare cases, longer. One-shot games are intended to be run once,

as a stand-alone experience, while campaign games run for years, decades even, spread over monthly or yearly events. Although larps are commonly called “games,” there is no winning or losing in the traditional senses; there is only having fun or not having fun, truly immersing oneself into a character and developing that character, or not. The performers themselves are the only audience, each player the ultimate judge of his or her own experience.

Essentially, larp is make-believe on steroids for adults. Computer games, with all their realistic scenery, are nothing compared to a larp. Sure, a computer character can wear cool armor and swoop through the detailed landscape of the game world, but in a larp, players actually stalk down their enemies in the woods, moving silently, muffling the jingling of their coin pouches.

There is no single sanctioning body of larpers, no tally of how many people participate in this hobby, but there are hundreds of larp groups across the United States, with memberships ranging from a few people up to hundreds. In addition, dozens of gaming conventions across the country feature larps as part of the fun each year. The twice-yearly conventions run by the New Jersey group Double Exposure, for example, draw hundreds of larpers. The hobby has a global following, with numerous groups in Europe and Australia. The convention Knutepunkt, which means “nodal point” or “knotpoint” in Norwegian, rotates around Scandinavian countries each year, changing its name according to the host language. Knutepunkt treats larp as an art form and is less a convention than a conference offering panels on the nature of larp itself. Each year it publishes a book of scholarly essays on the hobby.

If the idea of adult make-believeâgrownups in elf ears, dressed in bodices and Renaissance skirts, or clad in black trench coats and sunglasses indoorsâseems frivolous to you, you are not alone. Larp has a bad rap, conjuring pictures of jobless misanthropes living in their parents' basements. In fact, larp is so geeky a hobby that other geeksâcomic book lovers, reenactors, trekkies, and Dungeons & Dragons enthusiastsâoften pooh-pooh it as a lower form of nerdery. Despite the stereotype, I found many larpers to be employed, clever, and, yes, cool. It takes a certain self-assurance to put on a costume outside of

Halloween or a theatrical production and to play a swashbuckler or a mad scientist. And in a world full of digitized interactions, I found it remarkable that so many people were willing to make timeâonce a month, in some casesâto see one another and further the narrative.

Larp is far more than a game. It's a multimedia entertainment, an über-hobby, one that can encompass other forms of play. Many larps offer players games-within-games, from games of chance, such as poker, to contests of strength and balance performed with padded weapons. Players often show off other skills and hobbies during a larp. A singer might perform during a game set in a nightclub, a chef might play a cook and dole out real food to genuine compliments, and those skilled with needle and thread create fabulous costumes for themselves and others. Some players get into the technical aspects of larpâreading rules and crunching numbers to come up with the most favorable skill combinationsâwhile others blow off steam by killing monsters. There are players who love to solve game master-created puzzles or get into the heads of their characters. Others want to soak up an otherworldly atmosphere.

The saying “Entertainment is what you pay for, but fun you make yourself,” seems particularly relevant to larp. In order to make the game world more realistic, larpers are constantly on the prowl for cheap, everyday objects that might be transformed into props. The most obvious example is the transformation of PVC pipe and foam into a boffer, a homemade padded weapon used for combat in some games. One larp I attended built a primitive sprinkler system out of pipe at a Boy Scout camp to make it “rain” indoors on a band of characters. Sometimes, it's the thrift shop that provides costuming inspiration or tchotchkes that might help set a historical scene just so. Few game masters earn money from organizing events; rather, they do it for the joy of giving pleasure to others.

The drive to larp, to simulate reality for one's own edification and amusement, has ancient roots and modern applications. The Tudors of England enjoyed lavish, outdoor multimedia entertainments, for example, while the King Arthur-obsessed Victorians held medieval jousts with sometimes-disastrous results. Nowadays, many institutions use larp-like activities for educational purposes. Medical schools

enlist fake patients to help train their doctors, law schools run mock trials, and most impressively, the US Army builds fake towns, shoots mock explosives made of foam, and costumes its own soldiers with stomach-churning wounds in the service of pre-deployment training.