Legions of Rome (3 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

Once Tiberius became emperor the task of filling empty places in the legions became even more difficult. Velleius Paterculus, who served under Tiberius, made a sycophantic yet revealing statement about legion recruitment in around

AD

30: “As for the recruiting of the army, a thing ordinarily looked upon with great and constant dread, with what calm on the part of the people does he [Tiberius] provide for it, without any of the usual panic attending conscription!” [Velle.,

II

,

CXXX

] Tiberius, who followed Augustus’ policy of recruiting no legionaries in Italy south of the River Po, broadly extended the draft throughout the provinces.

Legionaries were not permitted to marry. Recruits who were married at the time of enrollment had their marriages annulled and had to wait until their enlistment expired to take a wife officially, although in practice there were many camp followers and many de facto relationships. The emperor Septimius Severus repealed the marriage regulation, so that from

AD

197 serving legionaries could marry.

For many decades, each imperial legion had its own dedicated recruitment ground. The 3rd Gallica Legion, for example, was for many years recruited in Syria, despite its name, while both 7th legions were recruited in eastern Spain. By the second half of the first century, for the sake of expediency, recruiting grounds began to shift; the 20th Legion, for instance, which had up to that time been recruited in northern Italy, received an increasing number of its men from the East.

When a legion was initially raised, its enlistment took place en masse, which meant that a legion’s men who survived battle wounds and sickness were later discharged together. As a result, as Scottish historian Dr. Ross Cowan has observed, Rome “had to replenish much of a legion’s strength at a single stroke.” [Cow.,

RL

58–69] When a legion’s discharge and re-enlistment fell due, all its recruits were enrolled at the same time. Although the official minimum age was 17, the average age of recruits tended to be around 20.

Some old hands stayed on with the legions after their discharge was due, and were often promoted to optio or centurion. There are numerous gravestone examples of soldiers who served well past their original twenty-year enlistment. Based on such gravestone evidence, many historians believe that all legionaries’ enlistments were universally extended from twenty to twenty-five years in the second half of the first century, although there is no firm evidence of this.

Legions rarely received replacements to fill declining ranks as the enlistments of their men neared the end of their twenty years. Tacitus records replacements being brought into legions on only two occasions, in

AD

54 and

AD

61, in both cases in exceptional circumstances. Accordingly, legions frequently operated well under optimum strength. [Ibid.]

By

AD

218, mass discharges would be almost a thing of the past. The heavy losses suffered by the legions during the wars of Marcus Aurelius, Septimius Severus and Caracalla meant that the legions needed to be regularly brought up to strength again or they would have ceased to be effective fighting units. The short-lived emperor Macrinus (

AD

217–218) deliberately staggered legion recruitment, for “he hoped that these new recruits, entering the army a few at a time, would refrain from rebellion.” [Dio,

LXXIX

, 30]

In 216

BC

, two previous oaths of allegiance were combined into one, the

ius iurandum

, administered to legion recruits by their tribunes. From the reign of Augustus, initially on January 1, later on January 3, the men of every legion annually renewed the oath of allegiance at mass assemblies: “The soldiers swear that they will obey the emperor willingly and implicitly in all his commands, that they will never desert, and will always be ready to sacrifice their lives for the Roman Empire.” [Vege.,

II

]

On joining his legion, the legionary was exempt from taxes and was no longer subject to civil law. Once in the military, his life was governed by military law, which in many ways was more severe than the civil code.

IV. SPECIAL DUTIES

Legions’ headquarters staff included an adjutant, clerks and orderlies who were members of the legion. The latter, called

benificiari

, were excused normal legion duties and were frequently older men who had served their full enlistment but who had stayed on in the army.

V. DISCIPLINE AND PUNISHMENT

“I want obedience and self-restraint from my soldiers just as much as courage in the face of the enemy.”

J

ULIUS

C

AESAR

,

The Gallic War

,

VII

, 52

Tight discipline, unquestioning obedience and rigid training made the Roman legionary a formidable soldier. Roman military training aimed not only to teach men how to use their weapons, it quite deliberately set out to make legionaries physically and mentally tough fighting machines who would obey commands without hesitation.

As one of the indications of his rank, every centurion carried a vine stick, the forerunner of the swagger stick of some modern armies. Centurions were at liberty to use their sticks to thrash any legionary mercilessly for minor infringements. A centurion named Lucilius, who was killed in the

AD

14 Pannonian mutiny, had a habit of brutally breaking a vine stick across the back of a legionary, then calling “Bring another!,” a phrase that became his nickname. [Tac.,

A

,

I

, 23]

For more serious infringements, legionaries found guilty by a court martial conducted by the legion’s tribunes could be sentenced to death. Polybius described the crimes for which the death penalty was prescribed in 150

BC

—stealing goods in

camp, giving false evidence, homosexual offenses committed by those in full manhood, and for lesser crimes where the offender had previously been punished for the same offense three times. The death penalty was later additionally prescribed for falling asleep while on sentry duty. Execution also awaited men who made a false report to their commanding officer about their courage in the field in order to gain a distinction, men who deserted their post in a covering force, and those who through fear threw away weapons on the battlefield. [Poly.,

VI

, 37]

If whole units were involved in desertion or cowardice, they could be sentenced to decimation: literally, reduction by one tenth. Guilty legionaries had to draw lots. One in ten would die, with the other nine having to perform the execution. Decimation sentences were carried out with clubs or swords or by flogging, depending on the whim of the commanding officer. Survivors of a decimated unit could be put on barley rations and made to sleep outside the legion camp’s walls, where there was no protection against attack. Although both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony decimated their legions, this form of punishment was rarely applied during the imperial era.

First-century general Corbulo had one soldier brought out of the trench he was digging and executed on the spot for failing to wear a sword on duty. After this, Corbulo’s centurions reminded their men that they must be armed at all times, so one cheeky legionary went naked while digging, except for a dagger on his belt. Not famed for his sense of humor, Corbulo had this man, too, pulled out and put to death. [Tac.,

XI

, 18]

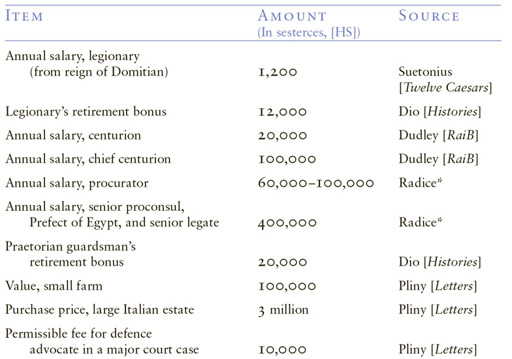

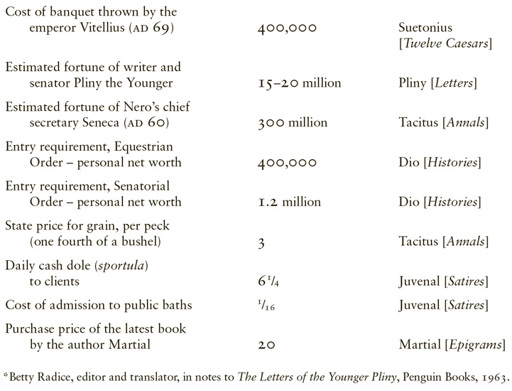

VI. LEGIONARY PAY

Julius Caesar doubled the legionary’s basic pay from 450 to 900 sesterces a year, which was what an Augustan recruit could expect. This was increased to 1,200 by Domitian in

AD

89. [Dio,

LXVII

, 3] Before this, Roman soldiers were paid 300 sesterces three times a year, installments which Domitian raised to 400 sesterces each. [Ibid.]

The legionary’s annual salary was infinitesimal compared to the 100,000 sesterces a year earned by a

primus pilus

, the most senior centurion of a legion, and the 400,000 a year salary of the legate commanding the legion. Deductions were made from the legionary’s salary to cover certain expenses, including contributions to a funeral fund for each man. Conversely, he also received small allowances for items such as boot nails and salt.

Another source of legionary income was the donative, the bonus habitually paid to the legions by each new emperor when he took the throne—300 sesterces per man was common. The legionaries normally received another, smaller, bonus on each subsequent anniversary of the emperor’s accession to the throne. In addition, emperors frequently left several thousand sesterces per man to their legionaries in their wills. Profits from war booty could also be substantial. After Titus completed the Siege of Jerusalem in

AD

70, so much looted Jewish gold was traded in Syria that the price of gold in that province halved overnight.

A legionary could lodge his savings in a bank maintained at his permanent winter base; his standard-bearer was the unit’s banker. In

AD

89, Domitian limited the amount each man could keep in his legion bank to 1,000 sesterces, after a rebel governor used funds from his legions’ banks in an abortive rebellion against him. [Suet.,

XII

, 7]

A soldier who fought bravely could have his pay increased by 50 percent or doubled for the rest of his career, and accordingly gained the titles of

sesquipliciarus

or

duplicarius

. Men with these awards were represented separately from the other rank and file when units submitted their strength reports to area headquarters, immediately following the optios and centurions on the lists. Men of duplicarius status proudly made reference to it on their tombstones.

To gain popularity with the legions, the emperor Caracalla (

AD

211–217), “who was fond of spending money on the soldiers,” increased legionary pay and introduced various exemptions from duty for legionaries. [Dio,

LXXVIII

, 9] Cassius Dio, a senator at the time, complained that the salary increase would add 280 million sesterces to the cost of maintaining the legions. [Dio,

LXXIX

, 36] In

AD

218, Caracalla’s successor Macrinus announced that the pay increase would only apply to serving legionaries and that new recruits would from that time forward be paid at the same rate as had applied during the reign of Caracalla’s father, Septimius Severus. This only hastened Macrinus’ overthrow that same year. [Ibid.]

VII. COMPARATIVE BUYING POWER OF A LEGIONARY’S INCOME (First–Second Centuries

AD

)

VIII. MILITARY DECORATIONS AND AWARDS

Legionaries who distinguished themselves in battle could expect not only monetary rewards. At an assembly following a victorious battle, soldiers would be called forward by their general. A thorough written record was maintained on every man in every unit, with promotions, transfers, citations, reprimands and punishments all studiously noted down by the man’s optio, the second-in-command of his century. The general would read the legionary’s previous citations aloud, then praise the soldier publicly for his latest act of gallantry, promoting him and often giving him a lump sum cash award or putting him on double pay, before presenting him with decorations for valor, to the applause of the men of his legion. Polybius recorded these awards, which continued to be presented for hundreds of years: [Poly.,

VI

, 39]

THE SPEAR: for wounding an enemy in a skirmish or other action where it was not necessary to engage in single combat and therefore expose himself to danger. Literally “the Ancient Unadorned Spear,” a silver, later golden, token. No award was made if the wound was inflicted in the course of a pitched battle, as the soldier was then acting under orders to expose himself to danger. The emperor Trajan appears to be presenting a spear to a soldier in a scene on Trajan’s Column.