Legions of Rome (4 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

THE SILVER CUP: for killing and stripping an enemy in a skirmish or other action where it was not necessary to engage in single combat. For the same deed, a cavalryman received a decoration to place on his horse’s harness.

THE SILVER STANDARD: for valor in battle. First awarded in the first century

AD

.

THE TORQUE AND AMULAE: for valor in battle. A golden necklace and wrist bracelets. Frequently won by centurions and cavalrymen.

THE GOLD CROWN: for outstanding bravery in battle.

THE MURAL CROWN: awarded to the first Roman soldier over an enemy city wall in an assault. Crenellated, and of gold.

THE NAVAL CROWN: for outstanding bravery in a sea battle. A golden crown decorated with ships’ beaks.

THE CROWN OF VALOR: awarded to the first Roman soldier to cross the ramparts of an enemy camp in an assault.

THE CIVIC CROWN: awarded to the first man to scale an enemy wall. Made from oak leaves, the Civic Crown was also awarded for saving the life of a fellow soldier, or shielding him from danger. The man whose life was saved was required to present his savior with a golden crown, and to honor him as if he were his father for the rest of his days. It was considered to be Rome’s highest military decoration, and the holder of the Civic Crown was venerated by Romans and given pride of place in civic parades. Julius Caesar was awarded the Civic Crown when serving as a young tribune in the assault on Mytilene, capital of the Greek island of Lesbos.

Entire units could also receive citations, and these were displayed on their standards.

IX. LEGIONARY UNIFORMS AND EQUIPMENT

In early republican days, each legionary was expected to provide his own uniform, equipment and personal weapons, and to replace them when they were worn out, damaged or lost. After the consul Marius’ reforms, the State provided uniforms, arms and equipment to conscripts.

The tunic and personal legionary equipment remained basically unchanged for hundreds of years. By Augustan times, the legionary wore a woolen tunic made of two pieces of cloth sewn together, with openings for the head and arms, and with short sleeves. It came to just above the knees at the front, a little lower at the back. The military tunic was shorter than that worn by civilians. In cold weather, it was not unusual for two tunics to be worn, one over the other. Sometimes more than two were worn—Augustus wore up to four tunics at a time in winter months. [Suet.,

II

, 82]

With no examples surviving to the present day, the color of the legionary tunic has always been hotly debated. Many historians believe that it was a red berry color

and that this was common to legions and guard units. Some authors argue that legionary tunics were white. Vitruvius, Rome’s chief architect during the early decades of the empire, wrote that, of all the natural colors used in dying fabrics and for painting, red and yellow were by far the easiest and cheapest to obtain. [Vitr.,

OA

,

VII

, 1–2]

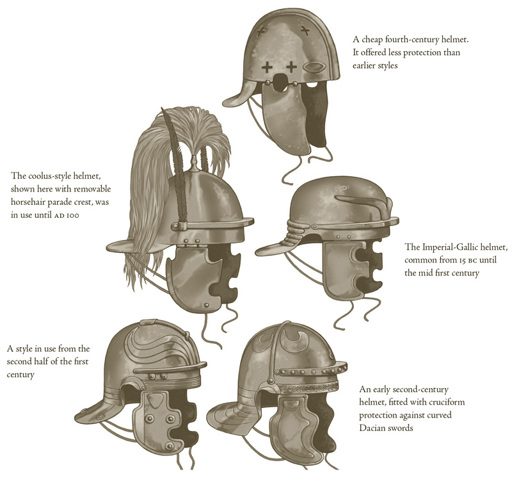

LEGIONARY HELMETS

Second-century Roman general Arrian described the tunics worn by cavalry during exercises as predominantly a red berry color, or, in some cases, an orange-brown color—a product of red. He also described multicolored cavalry exercise tunics. [Arrian,

TH

, 34] But no tunic described by Arrian was white or natural in color. Red was also the color of unit banners, and of legates’ ensigns and cloaks.

Tacitus, in describing Vitellius’ entry into Rome in July

AD

69, noted that marching ahead of the standards in Vitellius’ procession were “the camp-prefects, the tribunes, and the highest-ranked centurions, in white robes.” [Tac.,

H

,

II

, 89] These were the loose ceremonial robes worn by officers when they took part in religious processions. That Tacitus specifically notes they were white indicates that he was differentiating these garments from the non-white tunics worn by the military.

The one color that legionaries and auxiliaries were least likely to wear was blue. This color, not unnaturally, was associated by Romans with the sea. Pompey the Great’s son Sextus Pompeius believed he had a special association with Neptune, god of the sea, and in the 40s to 30s

BC

, when admiral of Rome’s fleets in the western Mediterranean, he wore a blue cloak to honor Neptune. After Sextus rebelled and was defeated by Marcus Agrippa’s fleets, Octavian granted Agrippa the right to use a blue banner. Apart from the men of the 30th Ulpia Legion, whose emblems related to Neptune, if any of Rome’s military wore blue in the imperial era, it would have been her sailors and/or marines.

Whatever the weather, and irrespective of the fact that auxiliaries in the Roman army, both infantry and cavalry, wore breeches, Roman legionaries did not begin wearing pants, which were for centuries considered foreign, until the second century. Some scholars suggest that legionaries wore nothing beneath their tunics, others suggest they wore a form of loin cloth, which was common among civilians.

Over his tunic the legionary could wear a

subarmalis

, a sleeveless padded vest, and over that a cuirass—an armored vest. Because of their body armor, legionaries were classified as “heavy infantry.” Early legionary armor took the form of a sleeveless leather jerkin on to which were sown small ringlets of iron mail. Legionaries and most auxiliaries continued to wear the mail cuirass for many centuries; there was no concept of superseding military hardware as there is today.

Early in the first century a new form of armor began to enter service, the

lorica segmentata

, made up of solid metal segments joined by bronze hinges and held together by leather straps, covering torso and shoulders. This segmented legionary armor

was the forerunner of the armor worn by mounted knights in the Middle Ages. By

AD

75, a simplified version of the segmented infantry armor was in widespread use. Called today the Newstead type, because an example was found in modern times at Newstead in Scotland, it stayed in service for the next 300 years.

On his head, the legionary wore a conical helmet of bronze or iron. There were a number of variations on the evolving “jockey cap” design, but most had the common features of hinged cheek flaps of metal, tied together under the chin, a horizontal projection at the rear to protect the back of the neck, like a fireman’s helmet, and a small brow ridge at the front.

First- and second-century legionary helmets unearthed in modern times have revealed occasional traces of felt inside, suggesting a lining. In the fourth century, the Roman officer Ammianus Marcellinus wrote of “the cap which one of us wore under his helmet.” This cap was probably made of felt, for Ammianus described how he and two rank and file soldiers with him used the cap “in the manner of a sponge” to soak up water from a well to quench their thirst in the Mesopotamian desert. [Amm.,

XIX

, 8, 8] By the end of the fourth century, legionaries were wearing “Pamonian leather caps” beneath their helmets, which, said Vegetius, “were formerly introduced by the ancients to a different design,” indicating the caps beneath helmets had been in common use for a long time. [Vege.,

MIR

, 10]

After a legion had been wiped out in

AD

86 by the lethally efficient

falx

, the curved, double-handed Dacian sword, which had sliced through helmets of unfortunate Roman troops, legion helmets had cruciform reinforcing strips added over the crown to provide better protection. It was not uncommon for owners of helmets to inscribe their initials on the inside or on the cheek flap. A legionary helmet unearthed at Colchester in Britain had three sets of initials stamped inside it, indicating that helmets passed from owner to owner. [W&D, 4, n. 56] In Syria in

AD

54, lax legionaries of the 6th Ferrata and 10th Fretensis legions sold their helmets while still in service. [Tac.,

A

,

XIII

, 35]

During republican times, Rome’s heavy-armored troops, the hastati, wore eagle feathers on their helmets to make themselves seem taller to their enemies. By the time of Julius Caesar, this had become a crest of horsehair on the top of legionary helmets. These crests were worn in battle until the early part of the first century, before being relegated to parade use. The color of the crest is debatable. Some archaeological discoveries suggest they were dyed yellow. Arrian, governor of Cappadocia in the reign

of Hadrian, described yellow helmet crests on the thousands of Roman cavalrymen under his command. [Arr.,

TH

, 34] The feathers of the republican hastati were sometimes purple, sometimes black, which possibly evolved into purple or black legionary helmet crests. [Poly.,

VI

, 23]

The helmet was the only item of equipment a legionary was permitted to remove while digging trenches and building fortifications. Helmets were slung around the neck while on the march. The legionary also wore a neck scarf, tied at the throat, originally to prevent his armor from chafing his neck. The scarf became fashionable, with auxiliary units quickly adopting them, too. It is possible that different units used different colored scarves. On his feet the legionary wore heavy-duty hobnailed leather sandals called

caligulae

, which left his toes exposed. At his waist he wore the

cingulum

, an apron of four to six metal strands which by the fourth century was no longer used.

X. THE LEGIONARY’S WEAPONS

The imperial legionary’s first-use weapon was the javelin, the

pilum

, of which he would carry two or three, the shorter 5 feet (152 centimeters) in length, the longer, 7 feet (213 centimeters). Primarily thrown, javelins were weighted at the business end and, from Marius’ day, were designed to bend once they struck, to prevent the enemy from throwing them back. “At present they are seldom used by us,” said Vegetius at the end of the fourth century, “but are the principal weapon of the barbarian heavy-armed foot.” [Vege.,

MIR

,

I

] By Vegetius’ day, a lighter spear, with less penetrating power, was used by Roman troops.

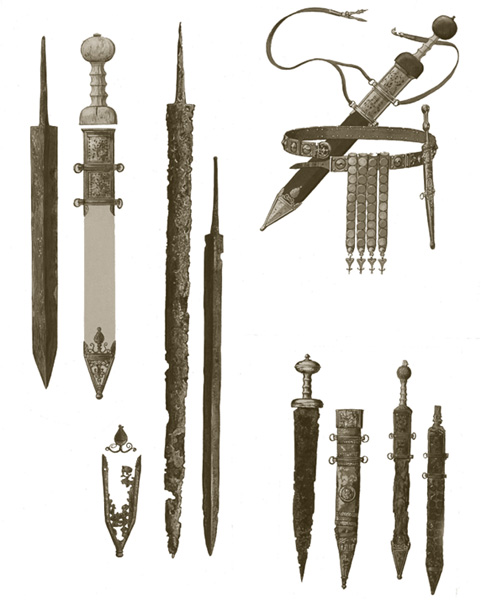

The legionary carried a short sword, the

gladius

, its blade 20 inches (50 centimeters) long, double-edged, and with a sharp point for effective jabbing. Spanish steel was preferred, leading to the gladius becoming known as “the Spanish sword.” It was kept in a scabbard, which was worn on the legionary’s right side, in contrast to officers, who wore it on the left.

Top right: Roman sword, a gladius, with baldric and dagger belt, mid to late first century AD. Bottom right: an early first-century AD gladius from Rheingoenheim and a sheath from the Rhine; a gladius found at Pompeii, and another now in a museum in Mainz. On the left: other swords found on the Rhine.

By the fourth century, the gladius had been replaced by a longer sword similar to the

spatha

carried by auxiliary cavalry from Augustus’ time. The legionary was also equipped with a short dagger, the

pugio

, worn in a scabbard on the left hip, which was still being carried into the fifth century. Sword and dagger scabbards were frequently highly decorated with silver, gold, jet and ceramic inlay, even precious stones.

The legionary shield, the

scutum

, was curved and elongated. Polybius described the legionary shield as convex in shape, with straight sides, 4 feet (121 centimeters) long and 2½ feet (75 centimeters) across. The thickness at the rim was a palm’s breadth. It consisted of two layers of wood fastened together with bull’s hide glue. The outer surface was covered with canvas and then with smooth calf-skin, glued in place. The edges of the shield were rimmed with iron strips, as a protection against sword blows and wear and tear. The center of the shield was fixed with an iron or bronze boss, to which the handle was attached on the reverse side. The boss could deflect the blows of swords, javelins and stones. [Poly.,

VI

, 23]

On to the leather surface of the shield was painted the emblem of the legion to which the owner belonged. Vegetius, writing at the end of the fourth century, said that “every cohort had its shields painted in a manner peculiar to itself.” [Vege.,

MIR

,

II

] While Vegetius was talking in the past tense, several examples suggest that each cohort of the Praetorian Guard may have used different thunderbolt emblems on their shields. The shield was always carried on the left arm in battle, with a strap over the arm taking much of the weight. On the march, it was protected from the elements with a leather cover, and slung over the legionary’s left shoulder. By the third century, the legionary shield had become oval, and much less convex.