LEGO (26 page)

Authors: Jonathan Bender

Steven breaks it down simply by saying, “Our products were there; we weren’t there yet.” Adult fans can serve as that bridge—helping to give product demonstrations at toy fairs and stores, acting as de facto salesmen for the company.

“If we gave them money for their services, it would be like an employer/employee relationship and we would lose their passion. We try to compensate these guys with the best commodity we have, which is LEGO,” says Steven.

LEGO had discovered how to turn the passion of adult fans into a tangible benefit for their company. And suddenly executives at LEGO were wondering just what else adult fans could do.

17

Protectors of the Brand

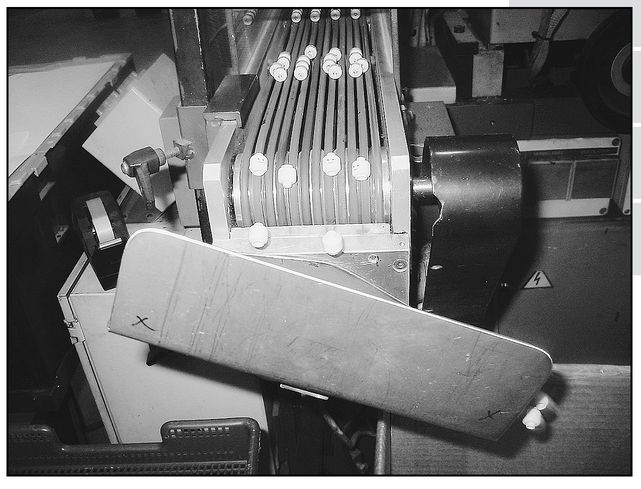

Minifig heads roll off the assembly line at the factory in Billund—just some of the approximately 36,000 LEGO elements made each minute. That’s about 19 billion a year.

My late grandfather was convinced that he could solve the energy crisis. He theorized that if we installed a pinwheeltype device on top of every car, we could harness the power of wind energy while driving. He submitted his idea to every major automaker, and every single one responded with a polite letter explaining that they could not even acknowledge receipt of his idea.

My grandfather just needed someone like Helle Friberg to believe in his ideas. The director of the New Business Group at LEGO is the person responsible for translating adult fans’ passion into a viable business model for the company. From Darth Vader cuff links to LEGO block-based Transformers—there’s a never-ending list of ideas submitted by people who are certain about what is the next big thing for LEGO. Helle gets to hear them all, because the LEGO Group thinks the future of its business could be in that slush pile. Somehow she is still smiling when we sit down with Tormod Askildsen around a white conference table in the back of the Havremarken building on my third and final day of meetings.

“Everything big turns small, so rather than try to single out a single business opportunity that will give us a billion dollars, we preferred to start up a lot of small initiatives, see them grow, and learn and experiment,” says Helle.

She runs a division where AFOLs are central to the business model envisioned by LEGO. The New Business Group has become a de facto venture capital arm for adult fans, acting as a business incubator designed to let LEGO and its partners experiment with micro businesses. The LEGO Group is trying to capitalize on the implicit trust among its existing brand ambassadors—the AFOL community.

“LEGO has one dominating business model. It’s the way we invent and bring new things to the market. It’s what LEGO has become after fifty years of business. So the idea is now to let people develop their own business on our LEGO platform. As a result, the person might just be more important than the idea,” says Helle.

In 2006, LEGO launched a pilot program under the New Business Group that tapped adult fans to design commercially available sets. It was an extension of LEGO Factory, which allowed users to virtually create and order a custom set using 3-D software on LEGO’s Web site.

“The idea was, wouldn’t it be neat if you could make your own LEGO set? So, we brought in some of the most talented fans to develop their own sets. They develop it and we publish it,” says Helle.

The New Business Group creative director Paal Smith-Meyer approached adult fans Chris Giddens and Mark Sandlin about designing two space sets. Star Justice and Space Skulls were released in April 2008.

The same year that LEGO began pursuing fan sets, the first third-party licensing agreement was signed. HiTechnic is a company that produces aftermarket sensors that are compatible with Mindstorms NXT. Then, in August 2007, LEGO agreed to provide a year’s worth of funding to

BrickJournal.

The adult fan magazine was able to transition from digital to print issues with the influx of capital.

BrickJournal.

The adult fan magazine was able to transition from digital to print issues with the influx of capital.

“BrickJournal

makes a lot of things happen, but it’s like any entrepreneur building a business. We want to get to the point that Joe [Meno] can develop

Brickjournal

as a medium to support himself,” says Tormod.

makes a lot of things happen, but it’s like any entrepreneur building a business. We want to get to the point that Joe [Meno] can develop

Brickjournal

as a medium to support himself,” says Tormod.

The goal was to limit the financial risk for Joe, letting him focus on community outreach and regularly travel to fan events.

BrickJournal

features information on new product lines, interviews set designers, and profiles prolific adult fans.

BrickJournal

features information on new product lines, interviews set designers, and profiles prolific adult fans.

“It was cool when they were interested. It was cooler when they said, ‘It’s your magazine,’” Joe tells me when I ask him about the contract.

The latest business to launch with the aid of the New Business Group is Brickstructures, which produces to-scale architectural models of famous landmarks. The principal is architect Adam Reed Tucker, the co-organizer of Brickworld.

“It’s a project that isn’t necessarily generating a huge amount of income for us, but it is an experiment in how to work with external partners,” says Helle.

LEGO leveraged the custom supply chain established through LEGO Factory to set up the back end of Brickstructures. With the limited release of the Sears Tower and the Empire State Building, LEGO can discover if batch production is efficient while establishing new distribution channels—Brickstructures will be sold in museum gift shops and at the landmarks as well.

Despite early partnerships for the New Business Group that focus on sets, Helle makes it clear that LEGO doesn’t see the entrepreneurship arm as a designer incubator. “It’s not our end goal to develop LEGO set builders out of great community builders,” says Helle.

That might not be the goal of the New Business Group, but the talent of some builders compels them to be noticed by LEGO. And some of those AFOLs end up working for LEGO, like Jamie Berard, thirty-three, an adult fan currently working in Billund as a set designer.

I almost get caught walking a minifigure across the white desk of a meeting room adjacent to the Idea House when Jamie walks in and shakes my hand, a smile on his face. It’s strange to see his hands punctuate his points in person; I’m used to watching them from LEGO’s Web site, where Jamie narrates a series of instructional videos on how to build simple shapes like columns. He has close-cropped black hair and the skinny build of somebody who seems to be constantly in motion.

Jamie was an avid LEGO fan growing up, spending hours building in the basement of his childhood home in Methuen, Massachusetts.

“Quite often, it would be three or four in the morning and then I would realize, oh, I’m supposed to be sleeping. I think it is part of the reason I don’t see myself getting bored or tired, because it’s not different from what I was doing,” says Jamie.

He always thought he would design amusement park rides, because as a child he didn’t know that LEGO hired designers. In 1985, LEGO released the Yellow Airport, and Jamie, at the age of ten, was already building like an adult fan. Despite receiving the airport set the previous Christmas, Jamie asked for it again the following year.

“I started asking for duplicates, because I saw there were some models that I never wanted to take apart because I loved playing with them and loved the themes,” says Jamie.

As his friends outgrew their LEGO sets, Jamie inherited their collections and before long had five Yellow Airports. Since LEGO was never a childish hobby for Jamie, he never went through the Dark Ages that stops the progress of a lot of adult builders. In 2000, a year after graduating from Merrimack University, Jamie began to chart the sales cycles in order to figure out when LEGO sets would be cheaper.

“I heard two adults talking in the toy store about buying sets for themselves and what they were building, which was definitely unusual. I was interested, so I asked the guy at the register if that was normal,” says Jamie.

He had just seen some of the members of the New England LEGO Users Group (NELUG). Jamie went to a meeting the next month and realized that he wasn’t the only adult building with bricks. Jamie had never given up on LEGO, but he also never stopped thinking about theme parks. He tinkered with motors to create LEGO amusement rides and got a job at Disney World as a monorail driver. There he discovered that adults will act like kids if you just take them out of their everyday routine.

“People expect that everything at Walt Disney World is going to be magical. That lets you tap into the idea that anything is possible, and suddenly you’ve convinced a whole train full of people that they have to lean around the curves in order for you to steer the monorail,” says Jamie.

But it’s difficult to earn a living at Disney, and Jamie returned to the Northeast, finding work as a carpenter. A new dream job opened up in 2003 when LEGO announced a nationwide Master Model Builder Search for candidates to join the six master model builders at LEGOLAND California.

Jamie made the finals, flying out to California to build at LEGOLAND. He constructed an airplane amusement ride where the planes rotated up, down, and around with the help of the wind. But after a day of building, Jamie’s was not one of the three names called. He would not be a master model builder. The loss crushed him.

But it didn’t stop his determination to work for LEGO. Jamie drove down to Enfield, Connecticut, to ask if there were any openings in the warehouse department—anything to get his foot in the door. In October 2004, he got his first opportunity, working as a volunteer on the LEGO Millyard Project, the largest permanent minifigure exhibit outside LEGOLAND. LEGO master model designers Steve Gerling and Erik Varszegi led the design and build team of volunteers like Jamie in six phases over two years.

“LEGO has a policy of not paying fans to help, but instead giving them free product, and that to me was sustenance. I would have worked day and night for the company, only expecting LEGO in payment,” says Jamie.

The three-million-brick exhibit, located at the SEE Science Center, is a historical imagining of the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, a former textile manufacturer, in Manchester, New Hampshire. Over eight thousand minifigures were used in staging the downtown Manchester scene as it might have appeared in 1900.

“I think most fans see building as their alone time, and bricks are so valuable to them, either on a sentimental or monetary level. To build in a group setting is a very different dynamic. For the first time I was being asked to build something—it wasn’t just what I wanted to build,” says Jamie.

He was one of a half-dozen foreman from NELUG who worked with fellow LUG members, but also with volunteers who weren’t necessarily adult fans. Steve and Erik would walk around, blueprints in hand, building a level of gray plates one stud high to lay the foundation for the project. That’s when Jamie had to help teach people to build, or at least to understand the blueprints.

“You have to translate it to somebody in a language they understand through bricks. And they have to have a good time contributing, but not be doing something we would just have to take down later,” says Jamie.

Although he was working alongside LEGO employees, he had no idea he was about to become one. In August 2005, Jamie attended BrickFest, an AFOL convention in Washington, D.C., to sit on a discussion panel with two master model builders and talk about the Millyard Project. He made the fortuitous decision to bring his LEGO Ferris Wheel. His skill as a builder, plus the work he had done on the Millyard Project, convinced LEGO executives that he had the ability to be a set designer. As part of the fan outreach program, they were looking to bring somebody into the company who understood the world of adult fans but also could learn to build sets for an audience of children. To put it in perspective, it’s like a movie executive showing up at Comic-Con, viewing a film made by one of the convention attendees, and offering him a development deal on the spot.

By 2006, Jamie was a production designer in Denmark designing new LEGO sets. He remembers packing a cargo container in preparation for moving to a one-bedroom apartment in Billund. When he looked at his lack of furniture and the fact that his clothes were five to ten years old, Jamie saw what LEGO had come to mean to him.

“I was packing up my life and taking stock of just how much LEGO I had. It made me realize my priorities and that the hobby was that important to me. There’s something about this medium that lets you get to know yourself better. The LEGO you have is really a reflection on you, and that’s pretty powerful,” says Jamie.

Set designers must continually work creatively around a series of constraints. New sets have to be built on time, under budget, and even in the right color. It might be time for a blue product, because the town line already has a yellow, red, and green set. When I learn this, I realize that not all fans would want Jamie’s job.

“I’m often building something that someone else wants. In fact, most of the time building things that a six-year-old wants. I haven’t been six for at least ten years,” jokes Jamie.

He works primarily on the Creator line, which tries to teach kids how to build cars, buildings, and sculptures. The first set he designed came out in 2007, a Fast Flyers kit that looked like a red-and-white F-14 jet. As part of the creation process, Jamie also had to adjust to model reviews—the last step before a product is considered ready for building instructions. Here, a set designer has to sit down with more experienced designers, who build his set to see if it needs any changes based on the building experience.

Other books

04. Birth of Flux and Anchor by Jack L. Chalker

City of Bells by Wright, Kim

Finally My Happy Ending (Meant for Me Book 3) by St. James, Brooke

By the Sword by Mercedes Lackey

Tales of Pirx the Pilot by Stanislaw Lem

Ryan's Bride by James, Maggie

The Witch's Stone by Dawn Brown

The Funny Man by John Warner

The Fine Print: How Big Companies Use "Plain English" to Rob You Blind by Johnston, David Cay

Wicked Magic by K. T. Black