LEGO (22 page)

Authors: Jonathan Bender

This might be the chicken-egg question of AFOLs. Do adult fans exist because LEGO has encouraged friendly competition and developed builders since childhood? Or is LEGO merely responding to the wants of a group of adults who dreamed of becoming master builders as children? It reminds me of a discussion at Brickworld that spontaneously arose during a talk about why adult fans go through a Dark Ages.

“How much is LEGO doing to support online communities?” asked Scott, an AFOL from Alabama.

“We were supporting Brickshelf for a time; but we stopped that and decided we needed to step back. We’re here to experience your community. But as soon as we take ownership, it’s not the AFOL community anymore. We need this community to be self-sufficient,” responded Steve Witt, a LEGO community relations coordinator.

Steve is in a unique position to comment on LEGO’s policies because he’s one of the adult fans whom the company has hired to try to define its relationship with the AFOL community. Only twenty-six, he’s arguably the most powerful adult fan in the United States. He also has instant credibility because not only does he have historic knowledge of sets, but he also still builds regularly. With bushy black hair and a thick goatee, Steve could be any young guy just out of college, eating lunch at Chipotle, still attached to Nerf guns, and playing World of Warcraft for hours after his day job.

The difference is that his day job is working for LEGO. After graduating from Texas Christian University, Steve wasn’t sure what he wanted to do with his degree in education. An avid space builder, Steve met Jake McKee, then LEGO community relations coordinator, through TEXLUG in Dallas. Jake agreed to take him on in 2003 as an intern, because LEGO had a hiring freeze at the time. After Jake left LEGO to launch his own consulting business, their two-man department had shrunk to one. In May 2005, Steve was promoted to head community relations coordinator just six months into the LEGO Ambassador Program.

After Brickworld, Steve and I play phone tag, and I don’t know what to expect from a conversation with him. At AFOL conventions, Steve has something of a split personality. There are the glib one-liners that shut down hecklers during Q&As and I think help him navigate the tricky position of knowing more information than he can share. But there is also an earnest side indicative of a person who wants you to like him, and there are the hints he can’t help dropping about upcoming releases.

“I like to think that I’m basically the same; although I do sometimes put up a bit of a front at conventions,” Steve says when I ask him what it’s like to be a LEGO fan inside the company. “You can see the difference between the two worlds in something simple: the fan community and the company even have different names for colors.”

But he’s not just a liaison at conventions. Steve is also the adult fans’ voice within the company, explaining how adult consumers might perceive or react to production decisions. He tries to reach out to employees to let them understand why AFOLs connect with their product. To do that means discovering what his coworkers are passionate about, be it action figures or fonts.

“My dad collects stamps. I see no point, but I appreciate that he loves it. Passion for anything doesn’t mean you’re crazy,” says Steve.

Toward the end of our conversation, I ask Steve about Dan Brown, telling him I just got back from the Toy and Plastic Brick Museum a few weeks ago.

“I don’t have that much interaction with Dan,” says Steve. It’s the only truly corporate answer I’ve received from a very noncorporate person. What he doesn’t say tells me a bit more about where Dan stands with the company. He’s outside, and LEGO is still deciding if they’re going to let him look in.

While talking to Steve, I’ve put together most of a World of LEGO Mosaics set. It’s the box I snagged at a thrift store for a dollar the previous month—a blue-and-white shark with flowing green seaweed on a clear baseplate. At sixteen studs by sixteen studs, it’s not much bigger than a bread plate, only taking the edge off my desire to build. I need something more.

I have a grand plan to build a monster black-and-white mosaic of Kate and me. I credit Brian Korte’s portfolio with the inspiration, having seen the black-and-white mosaic he made from a photograph to give his fiancée, Molly. Since then I’ve wanted to build something I could give Kate as a gift, and I have settled on a ninety-six-stud-square mosaic.

The picture I have in mind is from a vacation to Normandy, France, taken in our time-honored tradition of holding the camera out in front of us with one hand and getting a shot of our heads smushed together.

“Step 1 is reducing the pic to 96 pixels [by 96 pixels—so that each pixel is a Lego stud]. Then you’ll see what you’re dealing with. It won’t be pretty any more. This is what separates the programs from the artist,” writes Brian when I e-mail him for advice.

I open the vacation photo in Photoshop and set to tweaking it so it will make a good mosaic. I change the contrast on the photo to black-and-white and reduce the size of the picture. The image quickly morphs into an arrangement of blocks; it’s not even clear to me what each of the blocks represents. I begin to play with the levels and curves, hoping I remember enough from a one-day impromptu lesson from a newspaper editor in Revere, Massachusetts, about six years ago. I also adjust the portrait into five colors to match the LEGO color spectrum: three grays, white, and black.

“You have to capture them as a portrait, not mimic the photo,” Brian told me earlier when I asked how important it is to match the mosaic to the photo.

I print out four guides, each of which represents a quarter of the mosaic. I’m ready to build.

When he gets to this point, Brian told me, he often brings in friends to help him finish his large-scale models, buying them pizza in exchange for an evening of snapping the studs into place, following his printouts where one pixel equals one stud. He tells me that he occasionally hazes new builders by telling them that the LEGO logo (featured on each stud) needs to be facing the same direction on every brick of a studs-out mosaic. The positioning of the LEGO logo doesn’t matter; but I’m glad I’m not that naive.

I don’t have nearly enough bricks to even start my mosaic, so I get ready to place my first big BrickLink order. I spend two hours on the site comparison shopping before I realize that the cost of having bricks shipped from four different sellers negates any real cost savings. I’m disappointed that 1 × 1 white plates will cost me nearly six cents apiece, because I need 180 of them; but I’m ecstatic that 1 × 1 black plates are only three cents. I buy 7,790 bricks, doubling my collection with a click of my mouse. In one week, $224.76 worth of LEGO elements are slated to arrive at my house from Yorba Linda, California.

I get impatient waiting for the bricks to arrive, so I go to a local source for the green baseplates that will form the base of the mosaic. The rain falls softly as my car idles in front of a generic gray office building ten minutes from my house. The digital clock reads 12:15 p.m. It’s time to make the exchange. Andreas Stabno appears in the revolving door and motions for me to come inside.

“You got the stuff?” I joke. He’s brought six green baseplates, thirty-two studs wide and long. I hand him a check for $29. Andreas is glad to see that I’m working on a big project. I finally understand how he felt picking up the monorail set in the parking lot of a St. Louis train station.

I think about surprising Kate, but the dining room table will be my main workstation for the next few months, and I think she’ll figure out something is up.

“I bought six baseplates from Andreas today. I’m building a ninety-six-by-ninety-six mosaic for you,” I tell her. It’s easier to start with $29 and then work my way up to the BrickLink purchase.

“That’s great; but don’t you mean nine baseplates?” says Kate.

I pause; my master building project already has a pretty big problem. I’ve done my math wrong on an art piece that is basically a creative use of math. Six baseplates would leave me with a ninety-six by sixty-four mosaic.

“Right, that’s what I said, nine baseplates.”

But that’s the beauty of BrickLink, because five minutes later I’ve sent $15.33 electronically to Cincinnati, Ohio, for three green baseplates.

I get excited each day the mail comes, hoping it is the large box of bricks for my mosaic. Instead, my second LEGO BrickMaster set arrives, a nifty green army jeep with an Indiana Jones minifig. It’s one of the few sets I put together that I immediately decide I will not be cannibalizing for parts, because it’s Indy and you can’t disrespect Dr. Jones.

Building with LEGO has opened me up to my other fan tendencies, through both the sets and the other adult fans. The creative element of LEGO allows the fan experience to be more interactive. I’ve been exposed to a lot of different fanboys (and a few fangirls): the AFOL universe overlaps with comic books, Star Wars, and Harry Potter—all strong subcultures in their own right. In some cases, it seems that there is a direct correlation between geek attraction and building with LEGO as an adult; Indiana Jones and Star Wars fans often find themselves picking up plastic bricks after a long hiatus because of specially released sets.

But beyond a direct connection, part of me feels that adults who are willing to embrace LEGO and redefine a children’s toy are simply more confident in letting their geek flag fly. They’re willing to embrace their fandom in other areas and risk ridicule, because after all, what’s more geeky than playing with LEGO?

I’ve had only one interview in my career when I felt like a fan. In my first few weeks as a staff reporter for the

Lynn Journal,

I learned that Marshmallow Fluff was made in the paper’s hometown of Lynn, Massachusetts. I called and arranged a tour of the factory and was taken around by a member of the second generation to run the privately held business. Don Durkee spent a half hour showing me the manufacturing plant and the process behind making the iconic marshmallow spread of my childhood. I failed to ask a single question.

Lynn Journal,

I learned that Marshmallow Fluff was made in the paper’s hometown of Lynn, Massachusetts. I called and arranged a tour of the factory and was taken around by a member of the second generation to run the privately held business. Don Durkee spent a half hour showing me the manufacturing plant and the process behind making the iconic marshmallow spread of my childhood. I failed to ask a single question.

And now I’m about to embark on a second trip as a fan. I’ll be spending three days inside LEGO headquarters: touring the factory, the set vault, and the Idea House—the former home of Ole Kirk Christiansen that has been turned into an employee museum. I hope I can think to ask a few questions.

15

Danish Rocky and a Real Star Wars Expert

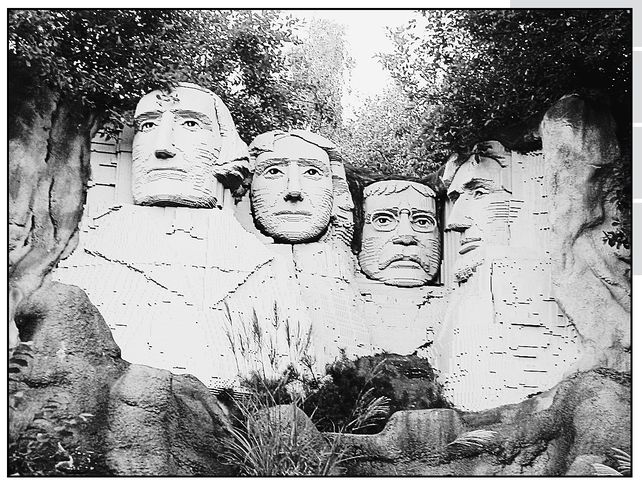

The 1.5-million-piece LEGO Mount Rushmore sits above Legoredo—the Old West reincarnated—at LEGOLAND in Billund, Denmark.

The C Terminal at the airport in Amsterdam has the least confusing duty-free stores of all time. Kate and I roll our bags past LEATHER, DIAMONDS, and SHOES. None interest me.

“Toys,” reads Kate aloud. “Want to go see if they have any LEGO?” But I’m already inside the shop. I buy a small catapult set explicitly for the dwarf and troll minifigs. I have no intention of building the kit, but I think I can use the green heads for a zombie build.

It’s late Saturday morning in the third week of September and we’re taking the commuter flight to Billund, Denmark, the headquarters of LEGO. I’m envisioning the plane filled with happy children—like the pre-island scene in

The Lord of the Flies.

But once we board, with the exception of a single ten-year-old, the rest of the passengers look like the businessman sitting next to me in designer jeans and a collared shirt.

The Lord of the Flies.

But once we board, with the exception of a single ten-year-old, the rest of the passengers look like the businessman sitting next to me in designer jeans and a collared shirt.

After the plane has taken off, I pull out a binder of articles concerning LEGO to prepare myself for my arrival at company headquarters. I stack these on top of

The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide

and start taking notes. I look up from reading and see that Kate is working on the Trebuchet set, having just snapped together a dwarf minifig.

The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide

and start taking notes. I look up from reading and see that Kate is working on the Trebuchet set, having just snapped together a dwarf minifig.

“Poor guy can’t bend his legs,” says Kate, noting that the dwarf’s legs aren’t hinged, making him shorter than a traditional minifig. A few minutes later, I hear an evil-sounding

razurrr.

Kate is walking a troll waving a black flag emblazoned with a white skull toward me. I burst out laughing, and the guy next to me looks up from his leather portfolio to give a polite smile.

razurrr.

Kate is walking a troll waving a black flag emblazoned with a white skull toward me. I burst out laughing, and the guy next to me looks up from his leather portfolio to give a polite smile.

My wife is a bit punchy after the overnight flight to Amsterdam, and we’re seated in an exit row—not a good combination. “Weapons test,” says Kate as she launches the 2 × 2 round brown projectile from the trebuchet and it shoots forward into the row ahead of us. Kate has to unbuckle her seat belt to retrieve the piece. We are relatively well-behaved for the rest of the hour-long flight. On touchdown, the man to my right gets up to grab his laptop bag from the overhead bin. It’s black with four primary-color LEGO bricks on the side and a red LEGO luggage tag.

“Enjoy your stay here,” he says, smiling before deplaning.

“Thank you,” I mumble, my cheeks reddening with the certainty that fate will make him one of the LEGO executives I’m destined to meet in the next few days.

There is no doubt that Billund is a company town. Any traveler landing at Billund Airport in 1964 would have disembarked in the hangar built for LEGO, just off the grass airfield owned by the company. An actual terminal wouldn’t be constructed for another two years. Today the airport is owned by the eight surrounding municipalities and sits just a half-mile from LEGO corporate headquarters.

Other books

Angel's Flight (A Mercy Allcutt Mystery) by Alice Duncan

Requiem Murder [Book 2 of the Katherine Miller Mysteries] by Janet Lane Walters

Ghost Thorns by Jonathan Moeller

The Work and the Glory by Gerald N. Lund

ICE BURIAL: The Oldest Human Murder Mystery (The Mother People Series Book 3) by JOAN DAHR LAMBERT

The Best Laid Plans by Lynn Schnurnberger

Love Bites by Barbeau, Adrienne

Tourists of the Apocalypse by WALLER, C. F.

King Of The North (Book 3) by Shawn E. Crapo

On Target by Mark Greaney