LEGO (9 page)

Authors: Jonathan Bender

But even in the worst year to date for the Danish company, its future identity and a considerable profit driver was being introduced: LEGO Mindstorms. The Robotics Invention System (RIS) was developed in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab. As part of a line of educational toys, Mindstorms came with two motors, two touch sensors, a light sensor, and a collection of LEGO Technic gears, axles, and bricks. Children ten years and older were encouraged to build their own robots using the kits, with a second version introduced in 2006 as LEGO Mindstorms NXT In the first twelve years, more than 1.3 million kits were sold.

But Mindstorms was not immediately the darling of the do-it-yourself community. The uncertain future of the company also led LEGO to look seriously at licensing opportunities, agreeing to create sets based on the Harry Potter and Star Wars series. LEGO was officially no longer just about bricks. The popularity of separate licensing lines convinced LEGO to offer a new intellectual property line that was completely outside the system of play. Bionicle (“biological” combined with “chronicle”), a product line of biomechanical beings from a science fiction world, appeared in Europe in 2000 and in the United States a year later. The figures would support a clothing line, a series of comic books, computer games, and DVDs.

LEGO was experiencing growing pains as the company sought to expand its identity. For every success like Bionicle, there was a Galidor: Defenders of the Outer Dimension—the short-lived action figure that didn’t win over many adult fans.

“Galidor is nothing more to me than a huge ink stain on Lego’s history, and signaled the lowest point in their dark ages (which I define to be from 1997 to 2004). The line was based on a failed TV show that lasted only one year, and was basically an action figure line with the Lego brand name slapped on. No studs, barely any technic pins, and pieces that are basically useless in any creations. I don’t even consider the line real lego [sic], and I’m extremely glad that TLC learned a lesson,” wrote the user Zarkan on the Bionicle fan Web site BZPower.

LEGO was about to discover the dark side of its adult fans.

“Fear is the path to the dark side. Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate,” warns Yoda in

Star Wars Episode 1: The Phantom Menace.

Unfortunately, LEGO didn’t have a Jedi Master on its payroll.

Star Wars Episode 1: The Phantom Menace.

Unfortunately, LEGO didn’t have a Jedi Master on its payroll.

LEGO’s financial struggles and disparate product lines made adult fans fearful that the company they had come to love was in danger of disappearing. They saw the classic story of a family business that just couldn’t adapt to a changing business environment. The fear developed into anger for a faction of adult fans who were frustrated by the company’s new moves toward products like Galidor that didn’t seem to hold any appeal for adults. The hate would follow shortly.

In 2004, the company faced a second crisis, losing $327 million. The Harry Potter franchise was tied in to the release of movies and failed to gain traction without a big screen offering to accompany new sets. The Bionicle line was thriving, but LEGO was having trouble predicting which sets would be successful, leading to shortages of popular models and overproduction of slower-selling sets.

Amid takeover rumors in which Mattel was mentioned as a possible suitor, the Kristiansen family made a decision to reinvest their money and hire a CEO from outside the family. Jørgen Vig Knudstorp, a former management consultant with McKinsey and Company and director of strategic development at LEGO, was tapped to revitalize the company. Drastic changes commenced.

Knudstorp identified two major areas that needed to be addressed immediately: the supply chain and the current cost structure. It was the back end of the business that was killing LEGO, not competition from video games or low-cost manufacturing in China.

The big-box retailer hadn’t existed when LEGO first began shipping to small toy stores. LEGO had two factories and three packaging centers in five different countries. They were making too many products in too many places.

In an effort to cut costs, LEGO also looked closely at its product mix. Those few primary colors initially available for LEGO pieces had grown to more than a hundred hues. The customization of the minifigures, often the most expensive part in a set because of the stamping required to provide detail, became more elaborate as faces and uniform details were added.

For every plastics company, the price of colored resin is going to be a major expense. Under Jesper Ovesen, chief financial officer, LEGO instituted a pilot program that considered a change in the ordering and production of the base substance for the bricks. By narrowing the list of suppliers and developing a system to track the cost of each element, LEGO suddenly could get a better idea of the true costs of every brick to leave the factory.

In 2004, the company changed the tones of brown, light gray, and dark gray as part of a move to shrink the palette to sixty-three colors. The colors were focus-grouped with customers and major retailers; however, marketers didn’t include adult fans in the development process.

“Focus groups will cheerfully run your company into the ground if they are leading your decisions. This goes for any focus group, AFOLs included,” wrote Jules Pitt on LUGNET in May 2004.

The colors were relaunched as light stone gray, dark stone gray, and “new” brown. Adult fans nicknamed the new gray “bley” for its bluish-gray tint and the feelings of

blah

that it inspired. AFOLs had a laundry list of complaints. Anger bubbled over into hate.

blah

that it inspired. AFOLs had a laundry list of complaints. Anger bubbled over into hate.

Some suggested that the new colors resembled MEGA Bloks bricks, which is like saying your Rolex looks like it came from a New York City street vendor. AFOLs felt betrayed; they felt that their collections had been rendered worthless, as the new shades weren’t visually compatible with the original gray bricks introduced in 1977. BrickLink sellers panicked, as the company’s decision changed the market overnight, drastically reducing the price of the gray inventories in the secondary market. Over time, the price of old gray would skyrocket, according to the principles of supply and demand. In the wake of the backlash, LEGO designated the three new colors as universal, pledging that they would never change.

“There is no possible explanation you, or anyone else, could offer that would legitimize a change to colors that are not compatible with their original versions. These new colors make the old versions look terrible, and this could easily have been prevented! Are the Lego designers and executives color blind? Making these colors ‘universal’ is not the answer. Making the original versions of these colors ‘universal’ is the correct choice, but it is clear to me that this company has no idea what its own products are all about.

“Proof is in the financial situation that Lego currently faces. I am sure it will only get worse,” wrote adult fan Greg Muri, who promised that LEGO had lost a customer.

With uneven profits and a declining toy market, LEGO couldn’t afford to lose customers. Although adult fans might constitute only an estimated 5 percent of LEGO’s buying audience, they have a dramatic impact on the other 95 percent. And that’s when Jake McKee, the first community relations coordinator, got involved.

Jake is skinny with light brown tennis fuzz hair and a closely clipped goatee. The Dallas native started at LEGO Direct, where the company sold sets and merchandise via a catalog and a corporate Web site. Jake’s experience working directly with consumers led to the creation of his new position in 2000, after which he spent six years as the main liaison between the North American adult fan community and LEGO. Better yet, the year earlier he had started building with LEGO again, reliving his own childhood through the LEGO Star Wars sets. Adult fans had a man on the inside. McKee worked to make the company understand the interests of adult fans and tried to explain to adult fans the realities of running a company.

“As I’ve said before, out of all bad things comes something positive. In this case, the positive is that there are many more people internally who understand your passion and interest,” Jake posted to LUGNET in September 2004.

Herein lies the heart of the tension between the adult fan community and LEGO as a corporation. AFOLs would always form a minority of the toy company’s customer base. But they would be a vocal minority, and just like Ross Perot, they wanted a seat at the table with the guys making the decisions.

Although LEGO might recognize that AFOLs were talented builders and, in many cases, tech-savvy brand loyalists, this raised an issue for the company: how do you value the contributions of customers who don’t directly impact the bottom line?

To AFOLs, listening was not enough.

“Understanding is but a small step towards what really matters. Let us know when they start to care,” was Purple Dave’s response.

6

Brick Separation Anxiety

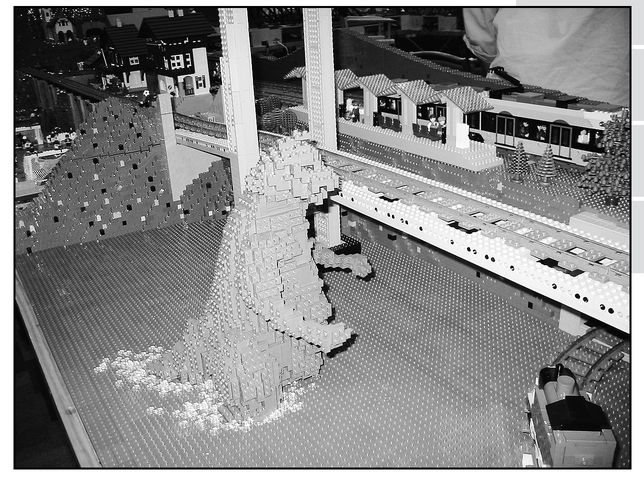

Godzilla emerges from the water hungry for train tracks in the Greater Midwest LEGO User Group’s twenty-foot display at Brickworld 2008 in Wheeling, Illinois.

I used to make fun of my dad for caring so deeply about when the mail arrived at his office. Then I started getting freelance writing checks in the mail, and now I figure I owe him an apology. In our Tudor-style home that was built in 1938, we have a slot to the left of the front door where our mail-lady slides in letters and magazines. The box that catches these can comfortably fit a postcard, so retrieving the mail often involves the same maneuver that leaves children’s hands stuck in Big Choice machines before the Claw gets them. I might not be completely ready to have kids of my own.

Working from home means that I’m the first to attempt this daily maneuver. After I hear the familiar plunk of a rubber-banded bundle, I reach in to find that my May issue of

LEGO Club Magazine

has arrived. I manage to get it out of the mail slot without ripping it, and start to flip through the pages. Based on the content, I can assume that I have raised the average age of their subscriber base significantly. It’s tied to the release of the LEGO Indiana Jones video game, which, even to an adult, looks pretty fantastic.

LEGO Club Magazine

has arrived. I manage to get it out of the mail slot without ripping it, and start to flip through the pages. Based on the content, I can assume that I have raised the average age of their subscriber base significantly. It’s tied to the release of the LEGO Indiana Jones video game, which, even to an adult, looks pretty fantastic.

It reminds me of the old

Nintendo Power

magazine, which was designed to complement the original eight-bit Nintendo. The

LEGO Club Magazine

is a mix of product announcements, sneak previews, contests, and a comic where the drawings have been given blocky, LEGO-esque features. There are a number of creations built by kids, and this again calls to mind the dispiriting effect of returning to skiing later in life. As on the slopes, it would appear that children are whizzing by me effortlessly, while I’m just trying to stay on my feet and not hurt myself in the process.

Nintendo Power

magazine, which was designed to complement the original eight-bit Nintendo. The

LEGO Club Magazine

is a mix of product announcements, sneak previews, contests, and a comic where the drawings have been given blocky, LEGO-esque features. There are a number of creations built by kids, and this again calls to mind the dispiriting effect of returning to skiing later in life. As on the slopes, it would appear that children are whizzing by me effortlessly, while I’m just trying to stay on my feet and not hurt myself in the process.

It is difficult to find benchmarks in the world of LEGO building. It’s not as if you can build at a fourth-grade level or emerge with a certificate of completion. There are no formal schools for training or lesson plans. So in the beginning, I rely on the age range recommended on the LEGO set package.

Kate comes home to find a small blue-and-white tow truck on my desk. The tiny Creator set, seventy-nine pieces, has been put together between the time she left for work and when she came back. LEGO is proving to be an outstanding tool for procrastination. In addition to helping me avoid my work, I find that buying smaller sets prevents me from having to unbox the Trade Federation MTT—the massive Star Wars set in the spare bedroom that has gathered a fine layer of dust, but so far has escaped the interest of our cat, Houdini.

“You are getting better,” says Kate, holding up the tow truck that evening.

“Well, not really. This set is rated for kids age six to twelve,” I admit.

“Well, you build really well for a twelve-year-old,” she says. I notice later that she picks up the instructions and considers the other two build options for the mini vehicle set. I tell her to feel free to build, but she declines, opting for a yoga class instead. Kate doesn’t yet know that my plan for returning to LEGO involves getting her to build alongside me. Phase one is set for the third weekend in June, when the second annual Brickworld is being held in Wheeling, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. Brickworld is a major AFOL convention, a three-day affair of building contests, lectures, and public displays. So, in two weeks I’ll introduce Kate to the world of adult fans—leading her around on one of the public display days—hoping it inspires her to want to build more.

As I pack up my bag to get ready for Brickworld, I consider bringing something that I have built to the convention. As with baseball card or craft shows, table space will be allocated, with LEGO user groups given adjoining tables to set up collaborative displays. Organizer Bryan Bonahoom, a boisterous rocket scientist from Fort Wayne, Indiana, whom I met at Brick Bash, sends an e-mail reminding everyone to submit information for their MOC (my own creation) cards. An MOC card is a white piece of paper folded in half with your name and the name of your creation that will be put at the front of the table to identify what you’ve built.

Other books

Extinction by J.T. Brannan

Interrupted by Zondervan

The Wild Ways by Tanya Huff

What Matters Most: The Billionaire Bargains, Book 2 by Erin Nicholas

My Lord Murderer by Elizabeth Mansfield

The Full Experience by Dawn Doyle

Reinventing Mike Lake by R.W. Jones

Tough Love by Cullinan, Heidi

Their Ex's Redrock Three by Shirl Anders

The Fantastic Family Whipple by Matthew Ward