Let’s Get It On! (21 page)

Authors: Big John McCarthy,Bas Rutten Loretta Hunt,Bas Rutten

DeLucia then fell back and nestled Baker’s foot into his armpit for a heelhook attempt. Amazingly, Baker countered the hold and escaped to his feet. Ladies and gentleman, we had a fight.

Another takedown and a reversal from each man later, DeLucia lined up a triangle choke, locking up Baker’s head and arm by creating a triangle with his legs around them. Again Baker fought his way out of the finishing move. DeLucia found the triangle choke again from his back, but this time he flipped to top position with it. DeLucia was in perfect position to start punching Baker, who’d faded under all the pressure.

I was a little startled when DeLucia started speaking to him. “Dude, I don’t want to hit you anymore. Just give it up.”

After eating a few more fists, Baker did.

The final opening-round match, which would lead off the live pay-per-view, matched Royce against five-feet-seven, 160-pound karate expert Minoki Ichihara. Again, Royce’s first opponent of the night had symbolic value. Karate had had a healthy run in the United States, thanks to films like

The Karate Kid,

and the Japanese Ichihara was viewed as mysterious and potentially dangerous. Of course, I didn’t think Ichihara had a chance. We were talking about a man who’d dedicated his life to a discipline that doesn’t allow strikes to the head.

If the other fighters had known I’d already studied jiu-jitsu under Royce for nearly a year, maybe they would have said something about me refereeing his fight. But I never thought I would have a problem with it, and I never did anything special for Royce.

In my mind, it was the same as being a police officer. When a child molester moved next to a school and the neighbors harassed him, I had to be impartial, protecting his rights just as I would any other citizen. I learned early on in refereeing that there would always be fighters whose personalities I liked more than others, but that didn’t mean I could treat one fighter better than his opponent once the bell rang. I couldn’t gamble with people’s lives like that. So when Royce entered the cage, it was simply my eighth bout of the night; that was all.

The bout played out predictably with Royce taking Ichihara down with his trusty double-leg and mounting him. Ichihara had zero knowledge of ground technique, so he held on to Royce’s body while Royce peppered him with the occasional punch. Royce finally pulled the lapel of Ichihara’s uniform across the Japanese fighter’s neck in a gi choke to coax out the tap.

The sixteen had been whittled down to eight.

In the first quarterfinal, my resolve was tested again. Patrick Smith was matched against ninjutsu expert Scott Morris. The two quickly clinched, but Morris lost his footing on his takedown attempt, allowing Smith to fall into full mount. Smith then proceeded to beat on Morris with fists and elbows.

Again I was pointing and screaming to Morris’ corner to throw in the towel for their fighter, who had essentially been punched unconscious. The cornerman looked at me, turned his back, and threw the towel into the audience.

Smith stopped only because he thought my yelling was directed at him. He jumped off Morris, ranted, and paced around the Octagon. I quickly moved Smith away from Morris just in case he got any ideas to resume his destruction.

The fight lasted thirty seconds from start to finish, and in that half a minute I realized this system wouldn’t work. Given the power, corners weren’t coming through when their fighters really needed them most.

Already UFC 2 was unfolding much differently than its predecessor, and I didn’t like what I was seeing. My view from the cage kept getting worse.

The next quarterfinal bout would become one of the most infamous of all the early fights because it included the show’s second alternate, Fred Ettish. A kenpo karate expert from Minnesota, Ettish had flown to Denver for the tournament with no guarantee that he’d get to fight. When Ken Shamrock had withdrawn with a broken hand, the first alternate had been moved into the tournament. When Freek Hamaker couldn’t continue with a hand injury, Ettish was called up.

Fred was like me. He believed in what the UFC stood for and wanted to support it any way he could. With twice as many fights to deal with that night, SEG and WOW were short-staffed and disorganized backstage, so they’d asked if Ettish would lend some manpower.

Fred was ferrying the fighters from the hotel to the staging area when Rorion found him to say he’d be going on. Ettish had less than ten minutes to find his cornermen in the audience and wrangle them backstage, change into his gi, and warm up.

Ettish patty-caked early kicks with Johnny Rhodes, who’d battered his first opponent for nearly twelve minutes earlier that night. The 210-pound Rhodes swiftly stumbled Ettish with a counter right hand, then pushed him to his back with a few follow-up shots.

I knew right away that Ettish wouldn’t be able to win.

Ettish tried to fend off Rhodes from his back by flailing his legs, but the next punch opened Ettish’s forehead and sent him onto his stomach. He covered up, but Rhodes pummeled him with fists and knees. Propped on his left elbow, Ettish stretched his right arm to keep tabs on his standing stalker, shaking his head to get some of the blood out of his eyes.

All I wanted to do was get Ettish out of there.

Rhodes didn’t have a lick of ground fighting knowledge, but he finally climbed on top of Ettish to find a way to finish the bout. Rhodes grabbed Ettish’s neck with his right arm for an improvised choke and squeezed it with his bicep.

I followed Ettish’s body as it flopped around the mat like a helpless fish pulled from the water. Then I saw the tap and jumped in.

A dazed and bloodied Ettish managed to blurt out, “I didn’t tap.”

Crouched beside Ettish, with his white gi and black belt stained with blood, I said, “Okay.” What else could I say? I knew I’d seen him tap. I guess he didn’t remember it because he was going out from the choke.

His battle had just begun. Over the years, no other UFC fighter has been as ridiculed as Ettish. Fans denigrated him, called his style fetal fighting, and launched websites to crucify a man for those immortal three minutes and seven seconds. All because he had enough courage to go in there, do the best he could with what he knew at the time, and show an immense amount of heart. Since that day, I’ve had nothing but respect for Fred Ettish.

In the other pair of quarterfinal bouts, grappler Remco Pardoel knocked out Orlando Weit with elbows on the ground, and Royce armbarred Jason DeLucia. Both were over in under two minutes, but I performed poorly in the latter one.

During Royce and DeLucia’s fight, I stood on the wrong side and missed the whole setup to Royce’s armbar submission and the inevitable tapout. I think I’d overestimated what DeLucia would be able to do because he’d been training in Brazilian jiu-jitsu for a few months. DeLucia tapped Royce’s leg nine times and tapped the mat seven times more when Royce fell to his side with the hold still in place.

Afterward, I told DeLucia, “I’m sorry I didn’t get to you fast enough.”

“Well, I was tapping,” he answered, slightly perturbed. DeLucia received no lasting damage to his arm, but there’s a famous picture of the armbar, Royce’s tense body stacked and extended into the air with teeth clinched, that captures my mistake plain as day.

Needless to say, I learned that my own positioning was as important as the fighters’ and I wouldn’t be able to see everything from any one vantage point. I’d have to keep moving.

In the semifinals, Patrick Smith submitted Johnny Rhodes with a standing guillotine choke. I’m glad Rhodes had been paying attention at the rules meeting when I’d told the fighters they could tap out with their feet if they had to. Rhodes did just that at the forty-five-second mark.

As expected, Royce submitted Pardoel in the second semifinal match, which advanced him again to the finals to meet Smith. The much larger Pardoel put up a struggle when Royce tried to take him down, but the Dutch fighter was open season once Royce got him to the canvas. Mounting Pardoel’s back and getting his hooks in, or wrapping his heels around the Dutchman’s legs so he wouldn’t slip off, Royce used Pardoel’s own gi under his chin to submit him with a lapel choke.

After the bout when I presented the winner, Pardoel tried to raise his hand, but I pushed it down. I guess he was used to winning.

The fifteenth and final bout of the night was upon us with Royce meeting the strong, aggressive kickboxer Patrick Smith. We called this the classic striker versus grappler match. Again, I had no worries for Royce, and apparently he didn’t either.

“If you put the devil on the other side, I’m going to walk into the fight,” Royce told the cameras before the bout.

Smith, the local Denver favorite, was far from the devil. He didn’t even connect with a kick before Royce had him in his arms to initiate the takedown. Once he got it, Royce mounted Smith’s chest in seconds and threw six short, bare-knuckled punches straight at Smith’s face. Smith looked like he was on the verge of tapping out, but his corner threw in the towel as I intervened. Seventy-seven seconds had passed.

I was surprised Smith had tapped so fast because he’d built up some steam during the show. Smith’s UFC 1 introduction video kept running through my head. Pedaling on a stationary bike with his short dreadlocks swaying back and forth, Smith said, “Hi, my name is Patrick Smith. I’m impervious to pain. I don’t feel pain.”

In an ironic display of respect, Royce and Smith embraced and exchanged words.

“You’re a tough man,” Royce said.

“You’re the best,” Smith replied.

Again, Royce was hoisted onto the shoulders of his ecstatic family, Rorion and Helio included, as he held an oversized show check of $60,000 over his head for the world to see. The memo line said, “For: Being the Best!”

Nobody was there to tell me, but I was aware I couldn’t congratulate Royce or celebrate with the rest of the team right then. I had to remain impartial.

Afterward, I met up with Elaine, and we went to the after party in a small ballroom inside the hotel.

“Mr. McCarthy, you’re fantastic,” Bob Meyrowitz said, handing me an envelope.

“There’s something extra in there for you.”

I’d been told I’d be paid $500, but they’d added an extra $250. They must have been happy with what I’d done.

I wasn’t sure I was, though. I believed in the UFC’s goal—to find the best fighting style—but I wasn’t thrilled about the methods used or the role I’d played to get us there.

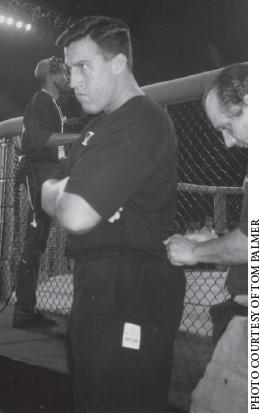

Keith Hackney, Kimo Leopoldo, Harold Howard, Roland Payne, and Royce meet the press at UFC 3 (September 1994)

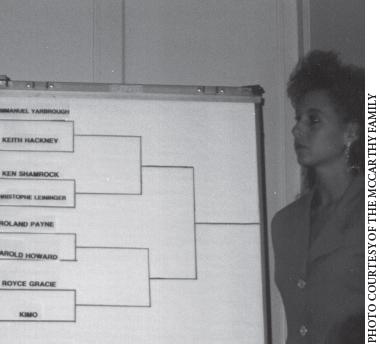

Royce’s future wife, Marianne, placing names on the board after the fighters are paired by number with the bingo machine for UFC 3 (September 1994)