Lilla's Feast (35 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Lilla must have seen Reggie there. Standing in the crowd. Waving at her, calling out to her and Vivvy furiously. Reggie, half his usual size, missing that crisp, pressed, open-necked shirt and the whistle around his neck with which he always seemed to be starting some race or umpiring some match. Reggie standing alone because his wife had made it back to England and his children had all gone off to nurse or fight in the war. Reggie smiling to see her, his eyes shining with relief that she was still alive.

Chapter 14

THE BIG CAMP

WEIHSIEN INTERNMENT CAMP, NORTH CHINA, SEPTEMBER 1943, ELEVEN MONTHS INTO LILLA’S IMPRISONMENT

The new camp spread out in front of Lilla in row after row of long, thin, gray huts as far as she could see. Here and there, the single-story skyline of this former missionary compound was punctuated by a taller building hovering over the tips of the low trees dotted along the alleyways and open spaces between the buildings. The pictures drawn by inmates show that each block was peppered with a row of door- and window-shaped holes, like a long line of animal stalls. A series of beams protruded out of the front of each row, like the side of a cage that had been temporarily lifted to let the creatures out. Clothes flapped from the wooden poles. A few graying sheets and towels seemed to skip just clear of the quagmire that must have been oozing like a lava flow through every gap the buildings allowed. “The monsoon rains were late that year,” writes Pamela Masters, a teenager who had gone straight into Weihsien from Tientsin with her parents and two elder sisters. The rains usually came in August, but when Lilla arrived in September, the camp pathways were still inundated, the compound a sticky sea of mud.

The mud stank. The stench must have hit the back of Lilla’s nostrils and the top of her throat as her bus rolled in through the camp gates. It was a reek “of rotting human excrement,” writes Masters. Of refuse and sewage. Of the discarded items that life leaves behind—which, in a way, was what the two-thousand-odd inmates of Weihsien, the remnants of the northern treaty porters, were. The elderly and schoolchildren. Taipans and civil servants. Prostitutes and thieves. An entire jazz band from Tientsin. Britons, Americans, Canadians, South Africans, Dutch, Belgians, Norwegians, Greeks, Cubans, Filipinos, Jewish Palestinians, Iranians, Uruguayans, Panamanians, a lone Indian, and even one German—a wife who had decided to follow her American husband and daughter into the camp. The people whose national governments had simply abandoned them to their fate. They had all been swept up in the great river of mud that was this war. Bundled together, rained on, and left to rot at the far end of the world, now distinguished only by the identification badges that they “had to wear at all times,” writes Murray, who, in an attempt to render this vast new camp less frightening to her youngest daughter, stitched a badge on her doll, too.

Weihsien internment camp: the perimeter fence, walls, and watchtower by the hospital block

Lilla and Casey were in either block 20 or block 8. The only record of who was where in Weihsien is a column of numbers jotted alongside a camp census typed up at the end of June 1944. The smudged room numbers were inserted after this, but nobody now knows when, or whether the internees were in those rooms for a night, a week, or a year.

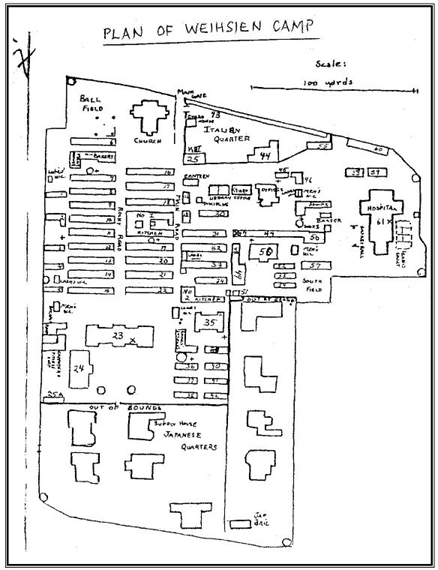

Plan of Weihsien camp, drawn by internee Langdon Gilkey

And what those numbers tell me is that, at some stage during their imprisonment, Lilla and Casey spent at least one night apart. Lilla in block 20, room 3, and Casey in block 8, room 5. As a couple of pages of prisoners’ names are missing, I don’t know whether they were alone in these rooms or temporarily sharing with the husband and wife of another couple. The elderly men in block 8, perhaps because it was near to the men’s showers and latrines, and the women in block 20. Or, I have been told, Casey may have been ill enough to need nursing care for a while. As there was only one ward in the hospital and many nurses—nursing being one of the few professions open to women back then—an interned nurse would move in with a patient, the rest of the patient’s family moving out to make room for her for as long as necessary. I don’t think it can have been that long. Casey may have been weakened by interrogation and imprisonment, but he would still make several journeys across the world in the years to come. In any case, although on first sight the number of buildings in the camp made it appear large—there were sixty-odd buildings in total, at just a couple of hundred yards square— it was all too compact a space for two thousand people to eat, wash, work, and sleep in. And blocks 8 and 20 were both off a black cinder pathway in the northwestern corner of the camp, known as Tin Pan Alley or Rocky Road, only a few yards away from each other.

The compound had a few large buildings containing old classrooms that were now being used as dormitories for the single men and women in the camp. The former missionaries’ houses—the most comfortable places there—had been taken over by the Japanese. The remainder, and the majority, of the camp’s accommodations consisted of those long, thin, gray huts that had originally been built as rows of single cells to house individual Chinese missionary students. Even before they had been abandoned, looted, and occupied first by Chinese soldiers and then by the Japanese, they had been spartan. Now they were miserable, and each had to house at best just a married couple, but often a family of four. The cells measured just nine by twelve feet—barely enough room to cram three mattresses onto the floor. The door and one window stood at the east-facing front, and there was a tiny opening for ventilation at the back. “The rooms had all been badly neglected,” writes Masters. “The white plastered walls were peeling and in need of repair, and the only electrical fixture was a ceiling lamp, hanging from a frayed cord.” And “there was no furniture,” points out Murray, “just a shelf on the wall.”

It was Lilla’s greatest domestic challenge yet. Less hospitable—and potentially hotter—than the Indian postings in which she had sweltered. Damper than the “rat-palace” in Kashmir. Less personal than Mrs. Bridges’s lodgings in Calcutta—and certainly smaller. And most galling of all, a stay that each day she must have hoped to see the end of. She had already been locked up for a year. Who was to say that she wouldn’t be locked up for another or more—two, three, four, or ten years, twenty even? If she survived that long. Perhaps, like murderers or other penitentiary lifers, she and Casey would die in prison.

Nonetheless, I can imagine Lilla doing her best to make their cell a home. She starts with the beds. Even the height of a mattress would at least keep them a few inches away from the cockroaches that hopped around the floor at night, occasionally landing on their faces. And from the rats that left their greasy slithers along the bottoms of the walls, “of which there were a number of varieties”—“providing the noisiest nighttime entertainment by far.” She pulls some slightly crumpled embroidered linen out of their cases. After a year in camp, it isn’t as fresh as it had been when she left home. Still, it is something with which to make their beds. Next she slides out the photographs and prints that she took from her home. Using pins, she tries to stick them onto the walls. Some fall back down immediately, bringing slabs of plaster with them and exposing the gray brick. With a great deal of huffing and puffing, she and Casey manage to shunt their cases into the empty corner of their room and arrange them to make a table and chairs, of sorts. Lilla sets out a couple of tiny painted china pots at one end, spreads a small embroidered tablecloth over the middle of the trunk. Finally, she pins up a couple of tea towels over the front window. Something to close them off from the camp outside and its two thousand pairs of eyes.

That’s one of the few things Lilla used to mention when she talked about the camp. That she had remembered to pack tea towels. And used them for curtains.

The one aspect of the room that would have defeated her was the lightbulb dangling from the ceiling. It hung there, ugly, bare, in the center of the tiny room, no doubt irritating her every time it caught her eye. Making her think that she ought to have brought a lampshade too.

Still, at last, she and Casey had somewhere to themselves. And a precious door with which to shut out the world outside. And here in Weihsien, the world outside their little space needed much more shutting out than it had in Chefoo. Instead of looking out on the familiar, still eerily beautiful ghost town of Chefoo that might any day spring back to life, Lilla now found herself looking out at a painfully brave new world.

Every aspect of the inmates’ lives in Weihsien was ordered by layer upon layer of ruthlessly efficient committees. “Everything was so much more sophisticated than at little Temple Hill,” comments Cliff. These had been set up by the first prisoners to arrive at Weihsien, on the instructions of the Japanese. By the time that Lilla and the rest of the Chefoo contingent arrived, the committees were a well-established hierarchy committed to the principles of “mucking in” and “pulling your weight” to an almost authoritarian extent. There was a supplies committee that rationed out food. There was an education committee in charge of an almost terrifyingly high standard of prisoners’ learning programs that ranged from biochemistry for children to Russian for adults to athletics taught by the Olympic 400 meter champion Eric Lid-dell, who was also interned in Weihsien, having been a missionary in Tientsin. A quarters committee distributed the prisoners among the cells and dormitory places as it saw fit. A discipline committee both decided upon and enforced the laws of the camp. And a labor committee allocated the camp’s mainly manual jobs according to each prisoner’s fitness and experience. Taipans and thieves alike were sent to clean the latrines, pump water for cooking and showers, eke out meals for hundreds on limited rations in the three camp kitchens, and keep the roofs on the decaying buildings.

The committees ran an extraordinary range of camp facilities. These included camp shops offering shoe mending, watch repairs, clothes mending, bookbinding, a barber, and a general exchange known as the White Elephant. There was even a financial service provided by the Tsingtao Swiss consul, a Mr. Eggar. Whenever he managed to visit Weihsien, he would distribute Red Cross “comfort money” to prisoners in exchange for IOUs that would have to be redeemed at the end of the war. There was a fully functioning camp hospital, although with limited equipment and supplies. Urgent cases obviously took priority, but prisoners with other medical needs found that these could be satisfied, too. Some female prisoners even chose to have hysterectomies there.

Furthermore, there was an impressive list of camp entertainments. Baseball and softball matches, cricket matches, soccer matches, rugby, touch football, band practices, plays, and musical revues were all put together to take up as much of the prisoners’ time as possible. The whole committee system seems to have been designed to hypnotize the prisoners with such an array of activities and duties that their minds had no time to wander to what might be happening outside.

It worked. Weihsien was its own little metropolis. A utopia of prison camps. “With such centralized organization, our community began to show the first signs of a dawning civilization,” writes Langdon Gilkey, who was in his early twenties and had been teaching at Yenching University. The committees admirably kept the prisoners alive and more or less healthy and sane. They did the best job they could possibly do. The only thing they could possibly do.