Lillian Alling (15 page)

The village of Prince of Wales, more generally known as just Wales, is located on the tip of the Seward Peninsula, 111 miles (178 kilometres) northwest of Nome. It has been the home of Inupiat Eskimos for thousands of years, and until the influenza epidemic of 1918â19 killed a large proportion of the population, it had been a major centre for whaling due to its strategic location on the animals' migratory route. By 1929, the economy was based mainly on subsistence hunting, fishing and trapping. Ales Hrdlicka, the Smithsonian anthropologist, visited the small settlement of Wales a few years after Lillian's journey. His diary notes,

Wales is a straggly village, or rather two villages, located on a large, flat, sandy spit, dotted with water pools and projecting from the Seward Peninsula toward Asia ⦠From the hills above it, the natives assure, one can see on a clear day the East Cape of Asia.

1

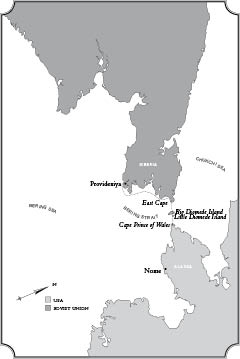

The Seward Peninsula was once part of the Bering land bridge, a thousand-mile-wide swath of land that connected Siberia with mainland Alaska during the last ice age, which ended about 11,700 years ago. It provided an entryway for plants, animals and humans to migrate from Asia to North America. After the ice melted and the waters rose again, the bridge disappeared beneath a shallow sea that was just 52 miles (84 kilometres) wide at its narrowest point between the continents. Cape Prince of Wales on the Seward Peninsula is the closest point on the Alaskan mainland to the mainland of Russia. Opposite it sits Cape Dezhnev or East Cape in the Soviet province of Chukotka. The Chukchi people who live there have traditionally made their living by fishing and hunting, and they traded with people from other regions in the Soviet Union and with the American mariners and traders who plied their trade in the Bering Strait.

In spite of strained relations between the US and the Soviet Union in 1929, the Native people of both countries still travelled regularly across the strait each year from June through Novemberâwhen the water is usually ice-freeâin order to trade and buy supplies. This traffic was either ignored or undetected by authorities on either side of the strait. In winter, groups from each side of the Bering Strait would would travel by dogsled, meeting off the Diomede Islands, which lie between the two countries, and camping on the ice. Little Diomede Island belongs to the US, while Big Diomede is part of the Soviet Union; the international dateline runs between them.

The boats used by the Native people on both sides of the strait were called umiaqs (or oomiaqs or umiaks), walrus-hide boats that were specifically constructed to handle the waters of the Bering Sea. Ruth and Bill Albee, who taught in Wales, Alaska, in 1934, gave a good description of the local boats in an article they wrote for

Practical Mechanics

in 1938:

In developing the oomiak, these Eskimos faced the problem of designing a boat for hunting walrus and whales in the stormy waters of Bering Strait with its crushing ice floes and treacherous currents. Since whales often weigh as much as fifty tons and walrus from 2,000 to 3,000 pounds each, they must be hunted by large crews. The boat must be capable of transporting eight to ten men, surviving heavy weather and bringing home the catch.

The oomiak is dory-shaped for seaworthiness, and from twenty-five to forty feet long. The frame is of light driftwood spruce, each piece carved to shape and the pieces lashed together with rawhide thongs ⦠Each oomiak is equipped with oars, paddles, mast and sail, and usually an outboard motor. The oars are used for long pulls, should the motor fail; the paddles for fast work amid ice floes; the sail to take advantage of favorable winds. Caught far out at sea, with a whale in tow, the crew may utilize motor, sail and oars simultaneously. We found no record of any oomiak crew at Cape Prince of Wales having been lost at sea.

2

In his book

Arctic Trader

, published in 1957, the well-known Alaska trader Charlie Madsen explained how Native people on both sides of the strait were happy to purchase motors from him:

When improved models replaced the earlier motors, I was able to barter quite a few outboards to natives along the Arctic Coast, at the Diomedes and King Islands, and Cape Prince of Wales. It became the custom for a number of Eskimos of King Island, the Diomedes and Cape Prince of Wales to unload their families, dogs, cooking utensils and food into umiaks equipped with outboards and sail to Nome for the summer, where they set up shelters outside the town ⦠[These motors] were accepted with wholehearted enthusiasm by Chukchis and Eskimos not only for long journeys but likewise in their hunts for seals, sea lions and whales.

3

However, it was not just the Native people who crossed back and forth between the two continents. Many Alaskan merchant ship owners, such as Charlie Madsen and Olaf Swenson with his ships, the

Nanuk

and the

Elisif

, were also regular visitors to the Siberian side to trade western goods for furs with the Chukchi people. As well, some of the North Americans who traded in Siberia moved there and lived with Chukchi women, thereby cementing relationships with the Russian people. Thus, although the Albees' postman had dubbed Lillian's plan to seek passage across the strait “a crazy notion,” it was not crazy at all. It was, in fact, quite reasonable for her to expect to travel to Siberia with Chukchi traders who were returning home from a trip to Alaska, or with Inupiat people from Alaska as they travelled to the Soviet Union. Alternatively, she could have hitched a ride with an American trader on a regular trip to the Diomedes and gone from there with Chukchi people to East Cape in Siberia.

The term Siberia is neither a political delineation nor an economic one. It is geographic and cultural, and usually means the area of the Soviet Union east of the Ural Mountains, continuing all the way to the Pacific Ocean and Bering Sea. It has diverse climates, cultures, peoples, languages, economies and ecologies. The remote Siberian villages in the Soviet province of Chukotka where Lillian would have landed relied on hunting, fishing and trading to survive. During poor fishing or hunting years, it was human against nature, and nature inevitably won. As a result, in the 1920s, the Soviet government set up a series of trading posts, which assisted with supplying both food and community connections and also provided control over the lives of the people in this area.

The Chukotka population was not literate in the late 1920s because the Chukchi did not have a written language; this did not begin to change until 1931 when the Soviet government implemented education in both Russian and Chukchi. As a result, in 1929 there were no newspapers in Chukotka,

4

although one paper from neighbouring Kamchatka,

Poliarnaia zvezda

(North Star), an organ of the Kamchatka District Bureau of the Communist Party, District Executive Committee and District Professional Union, was distributed there. However, my checks on its contents revealed nothing about Lillian or news of any foreigner landing on Siberian shores between September and December 1929.

5

I have also been unable to find any oral accounts as the region was sparsely populated, and the population later dispersed due to starvation. I could also find no official documents referring to her nor any other trace of her in Russian archives. In fact, I discovered that it is extremely difficult to get any information about the history of the Siberian coast in 1929.

In 1926, three years before Lillian made her journey across the Bering Strait, young John William Adkins from Maine had been working in Alaska when he decided he would try to obtain work in the Soviet Union. On July 27, in Nome, he hired Ira M. Rank's

Trader

to take him to Little Diomede Island. There he hired some Native people to take him in their skin boat to East Cape on August 1.

Adkins reported to the GPU (the State Political Administration, which later became the KGB) as soon as he landed. He had no passport and no visa, but he stated he was looking for work, and if he could not find work, then he wanted to take a Russian ship to Japan or Argentina. He received permission from officials to board the Russian ship

Astrakahn,

but when it stopped at Petropavlovsk he was arrested as an illegal immigrant by the GPU there, who were less accommodating than their East Cape counterparts. Adkins was

jailed for two months, but he was then given

permission to live and work in the USSR. Unfortunately, after working for a few years he fell victim to the Soviet terror and died in a prison camp.

6

*

I asked myself what could have happened to Lillian once she landed on Siberian soil. I believe the main problem she would have confronted, once in the Soviet Union, was the burgeoning bureaucracy of terror. It is possible that, like John William Adkins, she was immediately required to sign in with Soviet officials, and if, like him, she met with a friendly face, she may have been allowed to continue down the coast of Siberia. Alternatively, she may have come up against the full force of Soviet officialdom and been thrown immediately into jail. She appears to have had no passport that would allow her to legally enter the Soviet Union. Even if she held one issued by the pre-revolution Russian government, it would not have been valid under the new regime. In fact, it is not known whether she held a passport of any kind. Certainly she did not hold an American passport or she would not have been turned away at Hyder, Alaska. There is no record of her presenting any documents to the Canadian Customs officer at Niagara Falls, and in the three years she travelled across North America, she does not seem to have had any other identifying documents in her possession. (T.E.E. (Ern) Greenfield says that, when Lillian was arrested in BC, she carried a landing card showing that she had arrived in New York in 1927, but since she was already on her way across Canada by that date and he was recalling events some forty-five years after they happened, there is no proof that she carried this document. In addition, he is the only person to have mentioned it.)

Perhaps, though, she managed to arrive onshore unnoticed by anyone except local residents. Then the most likely scenario is that she remained in Chukotka for the winter because, if she set out alone and on foot across the treeless tundra at that time of year, she would not have access to her usual diet of berries and leaves and she would never have survived the desperately cold temperatures. It is possible, however, that she travelled farther inland by dogsled or reindeer team with Chukchi hunters. In the fall of 1928, Olaf Swenson, the Alaskan owner of the

Nanuk

and the

Elisif,

made an overland journey to the city of Irkutsk, hiring relays of dog and reindeer teams. The trip covered 4,300 miles (6,920 kilometres) and took 113 daysâthey often travelled day and nightâbut Swenson had the money to finance such a trip. As far as it is known, Lillian's funds were extremely limited. Perhaps, however, she could have afforded passage on a boat that would have taken her farther down the coast to a larger town before she headed west, although south of the tundra she would have met the impenetrable swampy coniferous forest of the subarctic known as the taiga. In his book

In Bolshevik Siberia: The Land of Ice and Exile

, explorer Malcolm Burr described the Siberian taiga as Lillian would have seen it in 1929:

And so we entered the taiga ⦠the huge, dense, impassable jungle where the trees struggle with each other to reach the light and upper air, where giants die and crash down to lay rotting on the ground and make soil for the next generation. It is a strange world. Only three roads cut it, the great rivers Yenisei and Lena, which run away to waste in the Arctic, and this great long ribbon of a railway which has cut its path through it from west to east. The rest is roadless, a mass of bog and rock covered by shrub and the endless forest with here and there an oasis cut by some enterprising settler in the neighbourhood of the [rail] line or along the trees.

7

It seems to me that where Lillian was headed after she landed in Chukotka would have depended on who she really was and what her final destination was. If she was a Polish national and was trying to return to Poland, her best course of action would have been to head all the way south to the port city of Vladivostok, which was, and is, the terminus for the Trans-Siberian Railway. From there she could have taken the train all the way to Poland. The main difficulty with that choice was that she would been checked regularly by customs and passport control. But if, lacking papers and money, she could not actually ride the train, she could have chosen to walk the 4,500 miles (7,240 kilometres) through Russia to Poland following the rail line. This would have allowed her to avoid passport control and other government representatives altogether.

If she was attempting to rejoin family members exiled to Siberia, it is uncertain what her destination would have been. Polish people had been exiled to Siberia for nearly a century and were scattered throughout the entire region. She may have had a difficult time locating them, although it is possible that she had received specific instructions before leaving New York State.