Little Casino

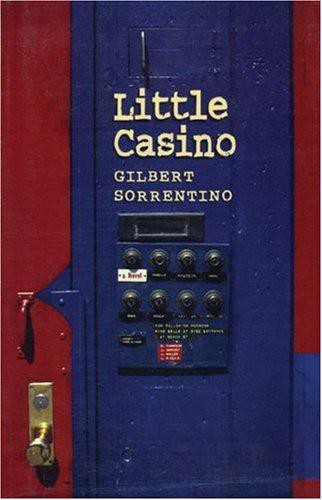

Little Casino

COPYRIGHT © 2002 by Gilbert Sorrentino

AUTHOR PHOTOGRAPH © Vivian Ortiz

COVER AND BOOK DESIGN Linda Strand Koutsky

COVER PHOTOGRAPH © Painet Stock Photos

COFFEE HOUSE PRESS is an independent nonprofit literary publisher supported in part by a grant provided by the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation by the Minnesota State Legislature, and in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Significant support was received for this project through a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency, and the Jerome Foundation. Support has also been provided by Athwin Foundation; the Bush Foundation; Buuck Family Foundation; Elmer L. & Eleanor J. Andersen Foundation; Honeywell Foundation; McKnight Foundation; Patrick and Aimee Butler Family Foundation; The St. Paul Companies Foundation, Inc.; the law firm of Schwegman, Lundberg, Woessner & Kluth, P.A.; Marshall Field’s Project Imagine with support from the Target Foundation; Wells Fargo Foundation Minnesota; West Group; Woessner-Freeman family Foundation; and many individual donors. To you and our many readers across the country, we send our thanks for your continuing support.

COFFEE HOUSE PRESS books are available to the trade through our primary distributor, Consortium Book Sales & Distribution, 1045 Westgate Drive, Saint Paul, MN 55114. For personal orders, catalogs, or other information, write to: Coffee House Press, 27 North Fourth Street, Suite 400, Minneapolis, MN 55401. Good books are brewing at coffeehousepress.org

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Sorrentino, Gilbert.

Little Casino/Gilbert Sorrentino.

p. cm.

isbn 1-56689-126-4 (alk. paper)

isbn 978-1-56689-288-9 (ebook)

1. Brooklyn (New York,N.Y.) — Fiction.

2. Autobiographical memory—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3569.07 L58 2002

813’.54—dc21 2001052943

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Some sections of this book have appeared in

Conjunctions,

to whose editor the author makes grateful acknowledgment.

When you look through binoculars, you are holding an instrument of precision and you see very clearly a small cabin which would seem quite indistinct without the binoculars. So you say, “Well, well, it’s just like another one I know, they are almost alike,” and as soon as you say that you no longer see it, in your mind you are comparing it with the one you think came

before,

while, in fact, it comes after. Truth means binoculars, precision, the thing that really comes first is the binoculars. You should say, “Well, well, these binoculars are almost the cabin.”

—ROBERT PINGET

Although we may catalogue a kind of chain mysterious is the force that holds the chain together.

—JOSEPH CORNELL

Contents

The very picture of loneliness

Clarity, neatness, and thoroughness

Mysteries of causes and effects

Little Casino

The imprint of death

P

EOPLE ENTER AND THEN INHABIT, HELP-

lessly, periods of their lives during which they look as if death has spoken to them, or, even more eerily, as if they themselves are companions to death. It is not usual for others to notice this in daily intercourse, but the look is manifest in photographs taken during these periods.

He and his wife stand side by side in casual summer clothes, comfortable, and, as they say, contemporary, but in no other way remarkable. Behind them is a cluttered, even messy kitchen table, in the center of which, curiously, a tangerine sits atop a coffee mug, and on the wall behind that is a very poorly done pencil drawing made by a neighbor’s daughter, a senior at the High School of Music and Art. Such infirm productions attest to the inevitable errors of talent selection. In the man’s face we can see, clearly, the imprint of death left there years ago by the deaths of his mother and father, who died less than a year apart. They died badly, as do many people, gasping, fighting, twitching, their staring eyes registering amazement at how their bodies were impatiently closing themselves down, literally getting rid of themselves. Enough! Enough!

And then they were gone, they

passed away.

His wife’s face has, uncannily, borrowed the subtly peaked, grayish blandness of his own, and so she, too, looks as if she has to do with

the other side.

But here is another photograph of a middle-aged man, let’s say he’s the wife’s brother, whose eyes, in a placid, contented, almost smug face, have the half-mad, glazed expression which used to be known, among infantrymen, as a thousand-yard stare. Precisely at the spot at which those thousand yards end, or, perhaps, begin, is the more precise word, stands death itself, in mundane disguise, of course, looking like James Stewart in one of his honest-friend roles. The face of the man in the photograph is unsettling, since its peaceful demeanor belies the crazed eyes, which reveal the dark truth. Death, as James Stewart, may have even been approaching when the photograph was taken. Which would go a long way toward explaining the ocular terror.

And here is a group of eight or nine children in a Brooklyn playground in 1959. There are four boys and two girls and they are smiling and mugging with their gap-toothed mouths, their shirts and shorts soaked from the sprinklers whose gossamer spray can be seen in the background. They are enough to break your heart. One of them, a sweet girl with straight black hair, cut short, and with a tiny Miraculous Medal on a chain around her neck, has her hands crossed on her chest. It is this pose which somehow allows access to the expression beneath the sweetness of her lovely face. The occulted expression is the one that can be seen on prisoners in Auschwitz, although this little girl knows nothing of Auschwitz. He puts the photograph down, he

hides

the photograph, but has no true idea why. Yet the message has been delivered, oh yes. It is at such times that we are brought to consider how completely strange death is, how remote from us, how foreign, how impenetrable, how unfriendly. In its ineradicable distance from our entire experience, it is inhuman.