Living Silence in Burma (40 page)

Read Living Silence in Burma Online

Authors: Christina Fink

10 A tea shop with a sign urging discipline in the background, Pa-an, Karen State, 1998

11 Villagers undertaking forced labour, Pegu Division, 2000

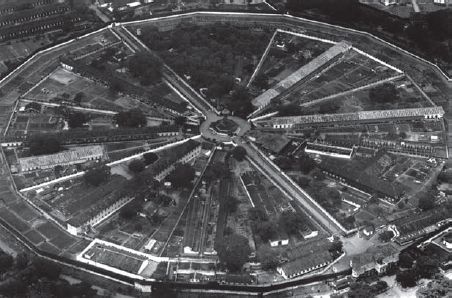

12 Insein Prison, where many political prisoners are held, just outside Rangoon, 2006

13 A man praying at Shwedagon Pagoda, Rangoon, 2006

14 A woman having her palm read, Rangoon, 2006

15 Organizing newspapers for delivery, Rangoon, 1996

16 Newly arrived refugees awaiting treatment for malaria and tuberculosis, Thai–Burma border, 1992

11 | The artistic community: in the dark, every cat is black

We have no true pleasure because we cannot share our thoughts. (A poet, Rangoon)

Writers, poets, film-makers, musicians and artists provide social commentary, express the deepest feelings of the people, and serve as creative forces that can inspire and motivate. Since the mid-1960s, however, their ability to communicate openly has been severely curtailed. Censorship boards operate in every field of public expression and impose harsh and often arbitrary judgements on the work submitted to them. Since 1988, successive military regimes have also used the carrot and the stick, bestowing awards and luxury goods on those who are loyal while threatening potential dissidents with oblivion. Most people in the artistic community try to walk a fine line between ensuring their ability to work and maintaining their integrity. Meanwhile, the authorities have sought to use the arts to project their own image of the country – as united and firmly rooted in Burman culture.

Writers pushing the boundaries

In August 1962, the Revolutionary Council promulgated the Printers’ and Publishers’ Registration Act, which stated that all printers and publishers must register with the Ministry of Information and provide copies of every published book, magazine and journal. This policy has remained in force ever since. The Press Scrutiny Board checks all publications, and this takes place not when they are in draft form, but after they have already been printed. In some cases entire books are banned and the whole print run has to be thrown away. In the past, magazine publishers were frequently ordered to delete certain paragraphs or even whole articles, so the publisher would have to go through every single issue inking over the section or ripping out the pertinent pages.

1

Magazine buyers would thus be aware of the hand of the censors when their magazine suddenly skipped from page 25 to 28, or when there was a silver square over a section of text. In the late 1990s, the regime decided to hide the work of the censors by requiring magazine editors to rewrite sections that were deemed inadmissible, so that the readers would never know that the magazine had tried to get across a more provocative point.

The effect of these practices is that authors and editors are under severe pressure to self-censor. Publishers don’t want to risk financial loss by having their books printed and then rejected. Likewise, magazine editors try to avoid being subjected to extra scrutiny and delays because of articles that push the limits. Thus printers and publishers often prefer to work with writers who do not challenge the boundaries, although a number do try to push the boundaries when they think they can.

Writers who have previously been imprisoned for their work or for support for the democracy movement are often blacklisted for many years. Worries about being blacklisted hold many writers back from trying to push the limits or participating in political activities. Nevertheless, some writers still try to express what they believe is important, usually in hidden ways. Maung Tha Ya is one writer who refused to compromise. After 1988 he wrote short stories that alluded to the killings of pro-democracy demonstrators. As a result, his work has been banned ever since.

2

In 2008, the well-known poet Saw Wei published a poem entitled ‘February 14’, about a man who is jilted by his lover. The poem seemed innocuous enough and easily passed the censors. But there was a hidden message: if the first letter of each line is read vertically, it says, ‘Power-crazy Senior General Than Shwe’.

3

Once readers detected this and the news spread, Saw Wei was arrested and sent to prison.

Some writers give in and write only about non-controversial topics, some focus on doing translations, and some stop writing altogether. Still, there are writers who are committed to the idea that they should act as the moral conscience of the nation, and they try to convey their messages through the use of metaphors and symbols. As Anna Allott has described in

Inked Over, Ripped Out

, such writers are confronted with a dilemma: if their metaphors are too obvious, the censors will catch them; if they are too obscure, not only the censors but also the readers will miss the point.

4

Sometimes the opposite happens, and readers impute meanings to the text that the author did not intend, or at least that s/he publicly denies.

Since the mid-1990s, the number of magazines and journals has grown rapidly, and they cover a wide range of subjects, including economics, domestic and international news and literature, as well as sports, entertainment and the occult. News publications have to publish as weeklies or monthlies because of the onerous censorship process, leaving only state-controlled daily newspapers. While a much wider range of information can be printed, particularly in periodicals that have good connections to higher-ranking authorities, the censors do not allow anything that they

think could make the regime look bad. All coverage of the monks’ demonstrations in 2007 was banned, and in the weeks after Cyclone Nargis, journalists could not get approval for any stories about the problems that survivors and displaced people faced.

5

Such stories implied the government wasn’t doing its job properly; only positive stories were allowed.

In addition, all publications must include the regime’s propaganda slogans on the first page. Under the SLORC and SPDC regimes, this has meant the ‘Three National Causes’: namely, ‘non-disintegration of the union, non-disintegration of national solidarity, and perpetuation of sovereignty’. Thus, even when reading a book or magazine in their own homes, people feel the presence of the state intruding. Moreover, magazine and journal editors are sometimes told to include commentaries by pro-regime writers which support the regime’s policies. To refuse would be to risk having the publication shut down.

Some writers in the mid-1990s tried to have an impact on society by promoting self-improvement and a can-do attitude. Translations of American advice books such as

The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People

by Stephen R. Covey sold rapidly, while editors of serious journals featured ‘overcome all odds’ stories translated from

Reader’s Digest

. One of the main proponents of this school of thought was a writer and public speaker named Aung Thinn. He advocated focusing on individual development, setting goals and using willpower to achieve results. Tapes of his motivational talks were extremely popular and sold well throughout the country.

Such ideas were criticized by more radical students, who saw them as a move away from broader political objectives and towards personal, and often materialistic, ends. Indeed, because the goals to which the self-help proponents were dedicated were not explicitly political, the regime allowed some of them to speak fairly openly.

Some proponents of the self-actualization school have argued that the restoration of democracy in Burma requires the development of a democratic culture, and a democratic culture depends on the widespread cultivation of management techniques, reasoning skills and self-reliance.

The regime, on the other hand, has promoted the idea that its leaders alone know what is best for society. Because the top authorities are sincerely working for the country, no one has the right to challenge their policies. This has led to a kind of numbness on the part of the general population. According to one writer who supports the self-actualization literature: ‘We need to fight our passivity.’ Many of the proponents of Western motivational techniques hope that by following concrete steps,

people will gain confidence in their ability to think and act. As one well-educated woman put it: ‘Fear has deprived a lot of people of their reasoning power.’