Loving Monsters (30 page)

Authors: James Hamilton-Paterson

– But in the meantime I had been banished to Hither Green. My mother wrote to tell me how sorry she was that I was a child of Satan and would need to be burned in everlasting flame. My

father wrote to Anderson & Green. I reclaimed and burned my incriminating diary. The

liber

if not the

amor

perished in flames. And at the end of all these writings and inveighings and burnings there was I, silent on a dock in Tilbury with a brand-new trunk and mixed feelings, as well as a Benson watch and fifty pounds from my father who tried not to cry as he tucked the envelope into my top pocket. So yes, by the time I arrived in Suez I was pretty glad to be out of it. That description I gave of my excitement at being abroad was accurate enough, even if it said nothing about the various traumas that had obliged me to be there. But since I was looking forward to seeing Philip imminently on his way through Suez I suppose I had all the motive I needed to stick it out. –

*

I took what I had heard back up the hill. This shocking revelatory morning had been capped by Jayjay informing me that he was dying. It was official, he said, and swore me to secrecy. He would tell Claudio and Marcella in his own good time. ‘Nobody’s indispensable,’ he said with a smile of remarkable sweetness. ‘They are when you haven’t yet finished their biography,’ I retorted. Oh Jayjay … No wonder you threw caution to the winds this morning and broke your silence. And there I was until only a matter of hours ago still complaining that you weren’t coming clean, that your life was boring me, that my own was more insistent.

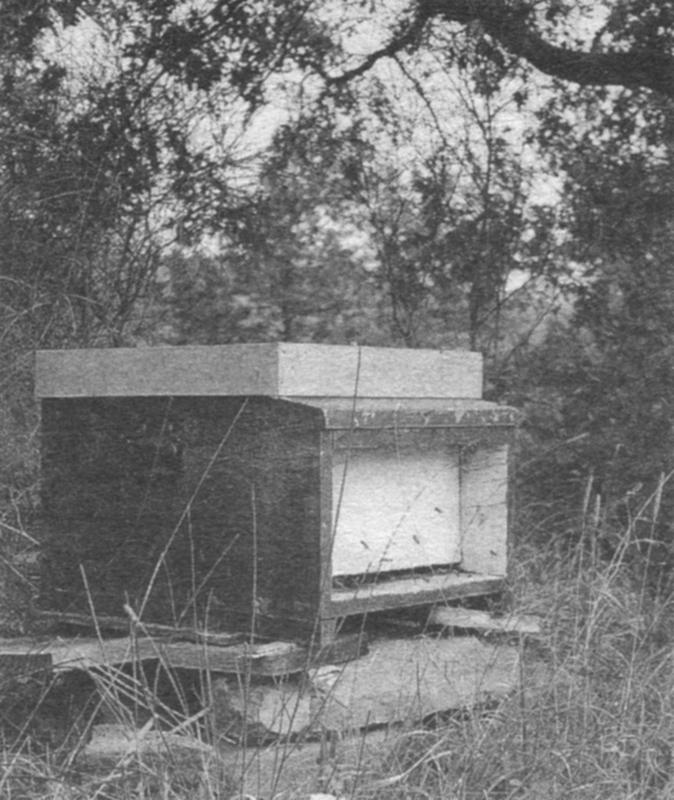

Sometimes I have this pressing desire to visit the bees and watch them on their sorties. Their unreflecting industry is an antidote to human messiness and travail, the love and tears of it all that billows up like cannon-smoke at Waterloo to obscure friend and foe and even the sun that might otherwise guide us home. At their busiest period in summer the worker bees live only a matter of weeks before they are worn out and their sisters (for they are all females) on corpse duty tug the bodies out of the hive and dump them on the entrance sill. Nobody’s indispensable. Most mornings there are two or three dead bees lying on the threshold of their home as evidence of brisk housework. The whole community

gives off an intense healthy smell hard to describe because it has such a wide range of associations. Of honey and sweetness, naturally, but equally of good housekeeping. There is a piercing cleanliness about it. Being obsessively clean, bees much dislike the smell of human sweat. To wear stale clothes while beekeeping is a solecism that greatly increases the chance of being stung. Even in the cool of dawn, summer hives diffuse their scent into the still air so powerfully they can be smelt fifty yards away. If work itself has a smell it is surely one of the components of this hive-scent and carries with it a faint hint of reproof, even of menace. These are creatures doing their living at a hectic pace and in their own arcane way. Our factory is our home, says the smell: you disturb us at your peril. Only those as clean and hard-working as ourselves have any right to the fruits of a labour that costs us our lives.

I often stand by the hives, sniffing this industrious incense that in some way slows the heartbeat. In fact, so restorative are bees that I invariably regain the one thing they conspicuously lack, a

sense of humour. I know I am back in kilter when I can say to them: ‘I’m sorry, girls, but it has to be said. When all your many virtues and talents have been duly listed and praised, we’re still left with one unignorable drawback: you’re dumb. Dumb, dumb, dumb. There’s so little flexibility programmed into you. I have only to move this hive two yards to one side and most of you will be unable to find your way back home again. Even a single yard would be enough to confuse you and, if it were winter, a good few of you would freeze to death inches from your own front door. That, I’m afraid, is

dumb

.

You’re going to have to do better than that if you ever want to take a step up the evolutionary ladder.’

To stand beside a beehive and laugh at its occupants for being easily disorientated may at best look like a small consolation. At worst one would sooner not speculate.

The sense of shortening time was confirmed by an almost imperceptible change in our arrangement. The sessions Jayjay and I had together were as frequent as ever but now less open-ended. After a couple of hours he would begin to tire. Six months was the span his doctors were predicting, the last part of which could hardly be expected to yield much in terms of work, and I had already inescapably committed two months of this precious allowance to my other book. With much difficulty I had arranged a further series of vital interviews in places as far apart as Hawaii, Canada and Australia where judiciously retired members of the old regime were living high off the hog. These were men, and in two cases women, who had reluctantly agreed to talk to me only after mutual friends had leaned quite heavily on them. The least appearance of casualness or date-breaking on my part would be as fatal as if I were to hint that my real mission was to write some sort of journalistic exposé. Now I would have to leave in a week’s time. I explained this apologetically to Jayjay.

‘I quite understand,’ he said. ‘The tug of the exotic, the light of tropic suns. Mind you, I feel it’s a little unseemly going on with this beachcomber act of yours when you’re easily old enough to be a grandfather. One only hopes you don’t do a Crusoe in cut-off jeans.’

‘Would that I could. This is a trip for well-cleaned shoes and a polite smile. Something you need never again affect.’

‘Only you, James, would have the appalling taste to turn a death sentence into a stroke of fortune. Still, thank you so much for pointing out the silver lining I might otherwise have missed. However, and joking apart, I’m perfectly aware you have your other work to do and must go. Don’t worry about it. Besides, there’s not so very much more I can tell you about myself now. I feel as though I’ve said it all, for what little it’s worth.’

‘But the great and the good? The Henry Kissingers?’

‘Oh, they’re easily dealt with. Still, you may remember that even before you agreed to take on this chore I did tell you that my first thirty years were the ones that counted. Probably true for most people, in any case. When I look back now the things of my life that seem most valuable and formative are all from that period and the recent half-century is a blur by comparison. That, I’m afraid, was the era of the great and the good. Not that I haven’t enjoyed much of it immensely. But it’s an odd irony that one should recall more fondly the process of learning how to live than doing the actual living. True of sex, too, I’m afraid. It was a revelation to start with but degenerated into a mere pleasure.’ Jayjay looked reflective for a moment then suddenly waved an elegant hand to indicate the beamy sitting-room, the terrace beyond the open French windows, the famous garden. ‘What am I going to do with all this

stuff

?’

‘It depends on your spirit of malice, Jayjay. You can always leave this place to someone with the proviso that it is converted for

agriturismo.

That way you can ensure the Valle di Chio will be made privy to the bayings of pink foreigners on holiday losing their tempers with their kids. It will be highly instructive for the

locals about cultural difference, especially if the foreigners are British. You know, the whole rigmarole that begins with always getting up too late to go anywhere or shop properly. There’s the mother who vaguely feels she wants to see Fine Art and the father who’s grumpy at having to pretend he does, too, although he’d far rather sit in the shade and get pissed because it’s so damned hot. Those excursions with the children in the back of the car, surly with computer games, barely appeased by promises of ice creams and swimming pools … Yes, I think you could do worse than leave that as your legacy to the neighbourhood.’

‘Heavens, James, what an unspeakable father you would have made.’

‘It’s true.’ I have never told Jayjay about Emma. I am indeed an unspeakable father.

‘But I don’t feel at all vindictive, and least of all towards the Valle di Chio which has given me generous shelter these last twenty-odd years. Well, these are my problems, not yours. A week, you said? We’d best return to Egypt at once and finish up there.’

‘Before we do, Jayjay, could I just get something straight about Adelio? In the light of your recent revelations, that is.’

‘Were we lovers, you mean?’ he pre-empted me with slight impatience. ‘No. Not exactly. I shall explain all, while at the same time glumly registering how depressing it is that from now on you will inevitably suspect my motives if I betray the least interest or concern for any male below the age of sixteen. You don’t have to protest,’ he added, raising a conciliatory hand. ‘It’s a sign of the times we live in. Once those stupid categories have been imposed no-one is allowed to fall between them. Pseudo-science has spoken. If you’re not this you’re that. One can never again be something quite other.’

A further sign of the times was that Marcella came in to ask if I wanted coffee. Hitherto she had let us fend for ourselves but I could see she was now keeping a firm eye on Jayjay. I had no doubt that if she thought I was over-tiring him she would ask me

to leave. Nor was he any longer allowed coffee on his previous awesome scale. Apparently the doctors had told him that at his age the body’s metabolic rate is quite slow, which is why they were able to talk in terms of six months rather than three. They alleged that gingering things up with large doses of caffeine was quite the wrong thing to do in the circumstances. These days Jayjay had to make do with tisanes, and he would stare sadly at the bloated sachet as it floated at the rim of his cup like a corpse in a pond, diffusing a thin ichor. The world divides itself into coffee-and tea-drinkers and the two seldom overlap.

*

– By the end of May 1941 Crete and the Balkans were in German hands and Axis forces were again massing on the Egyptian border. Once more things looked bad for us up in Alexandria and they suddenly looked worse still when the Germans began bombing the city. Churchill had already warned Mussolini that if he bombed Cairo the RAF would bomb Rome but Alexandria was obviously considered fair game.

– That first raid was chaos. We were told to stay put while they tried to evacuate civilians. But the more the sirens went and the Germans tried to hit the harbour and the main station, the more I realised nobody knew what to do. There were no real contingency plans. Or if there were, the right people hadn’t stayed to implement them. My only thought was for the Boschettis. I left SOE’s warehouse in Sid Dix’s charge and went straight to their flat. There, parked right outside, was the Hungarian Count’s Delahaye. I roared inside brandishing the Webley revolver I’d been issued and which I’d never loaded. I found everyone huddled on the kitchen floor, including Bathory-Sopron who had an antimacassar wrapped around his head. I was amazed to find anybody there. I assumed that the Italian legation would have taken care of its own but to be fair no-one really knew what the hell was going on, the wretched Italians least of all, given that they were now being blitzed by their own allies. The Count, meanwhile, turned out not to be injured, merely petrified. I got the family out of the

house and into the Delahaye, grabbing a spare tin of petrol I had in the back of the Fiat. At the last moment the Count tried to get in. He still had the antimacassar wrapped around his head. I was suddenly infected with Adelio’s loathing of the man. I shoved the muzzle of the revolver into the area of his moustaches and told him to start walking. I then hopped behind the wheel of his car and tried to head out of town, hoping to reach the Damanhur road.

– Bombs were going off in the distance, the roads were a mass of refugees, carts, panicked horses and so on. It was a bit of a nightmare, really. And yet in the middle of it all I remember seeing a lemonade seller calmly sitting under a tree with his brass urn, offering refreshment to the people as they stampeded past him. Then there was a massive explosion right behind us and the car was kicked forward by the blast. There was a shriek from Adelio in the back to say that their house had been hit

and

the Morettis’

and

the Lebanese restaurant

and

Mr Abbas’s laundry was on fire. Eventually we did get on to the Delta road and joined the general stream of traffic. At this point I had no idea what I was doing or where I was going. I wasn’t a proper combatant but oughtn’t I to stay in Alexandria and look after the warehouse? So powerful is the urge to join refugees streaming away from a skyline marked with boiling black clouds of smoke that I just glanced in the mirror and kept going. ‘

Madonna

santissima

,’

Mirella kept on saying fatalistically. ‘

Madonna

car

a.

We’re as good as dead.’ ‘I don’t suppose you have any

documenti

on you?’ I asked. ‘No passport or anything?’ But of course none of them had a thing and presumably all their private belongings were now entombed in the inferno of their apartment block. I had no idea how I could explain myself and this carload if we ran into a military checkpoint, as we surely would outside Cairo if not in Damanhur or Tanta. By now I was assuming that the raid was a softening-up operation as a prelude to Rommel’s full-scale invasion, and there seemed no future in going back to Alexandria, not even for Mirella and her family. I told her I was heading all the way to

Cairo where she and the children would just have to throw themselves on brother Renzo’s mercy.

– And a strange drive we had of it, too. Mirella climbed into the back to comfort Anna, who was petrified. Adelio seemed not to need comforting and took her place in the front seat on my right. As a matter of fact he appeared to be enjoying himself, as I suppose you can when you’re fourteen, have just seen your mother’s detested lover left at gun-point in the middle of an air raid and are now speeding along in the man’s coveted roadster. He had always said he wanted to leave Alexandria and now he was. To my surprise we made it through Damanhur and Tanta without being stopped. I think the car impressed the Egyptian army. But we were stopped outside Cairo where we were diverted on to the Heliopolis road to make way for a stream of British army lorries heading for Alexandria. The road block was manned by the Egyptian army but staffed by British officers who couldn’t recognise any of the codes on my ID card and were downright difficult about the poor Boschettis. In my case SOE was supposed to be so secret that not even the military knew about it, and anyway at that time Egypt was full of irregular units of varying degrees of secrecy and known by a bewildering variety of codes and nicknames. I remember my warrant card meant nothing to these fellows, unfortunately. Much telephoning went on before I was put through to someone who could vouch for me. Actually he was the chap who had fixed my temporary secondment to Alexandria. I told him I was bringing in an Italian diplomatic family who had current knowledge vital to our interests or some such nonsense.

– Finally they let us through and I took them straight to Renzo’s flat. He was in, and unfortunately for him so was his Greek boyfriend Kostas in a speedily donned Charvet dressing-gown. Renzo explained away this gorgeous apparition none too convincingly as a business associate who had been taken ill. I think only little Anna believed it but there were more important things to worry about. At least the Boschettis were reunited with Renzo and for the moment safe, if badly hampered by having no papers.

I was anxious to get back to Alexandria and save what little I possessed, including a trunkful of pornography, before marauding Axis troops could loot the contents of my flat. But I didn’t succeed in leaving Renzo’s without hearing the beginning of fulsome accounts by Mirella and Adelio of how I had saved their lives. It’s funny, until then it hadn’t occurred to me that there was maybe some truth in this. Had I not gone to their apartment and virtually bundled them down the stairs at pistol-point they would no doubt still have been crouched in the kitchen when the flat was hit five minutes later. That part was sheer chance; yet it was a sheer chance that was to lead all the way to this very house in Tuscany. And in turn that was due to Adelio, who in some ways was the strangest child I ever met. At the time I was still trying to fathom his behaviour of the previous week, just before the raid on Alexandria. –

*

It is the last time they would drive together to a beach, although neither of them knows it. The tension in Alexandria is worth escaping if only for the afternoon. The powerful Italo-German forces are halted only fifty miles to the west. In the kitchens of Pastroudis and other fashionable patisseries pastry chefs with icing bags are writing

Viva

l

’

Italia

and

W Il

Duce

on the new batch of cakes in order to display them in time for the invaders’ arrival. They also spell out

Sieg

Heil!

and, as though greeting tourists rather than troops,

Willkommen

in

Ägypten

in flowing blue and pink icing. Jayjay has wangled a free afternoon and he and Adelio are heading eastwards along the coast in the dented Fiat, away as if by instinct from the advancing front. This time, by the sort of mutual consent that is unspoken, they drive well past Faroukh’s palace at Montazah and out along Abu Qir bay. The road is deserted. Soon it shrinks to barely more than a dust track, a causeway between the sea on the left and Lake Idku on the right. On a small rocky promontory they come upon the remains of a tower. As he parks the car in its shade Jayjay explains this was a lighthouse that was struck by a stray salvo

from one of Nelson’s ships in the battle of 1798. There is evidently something in the place and the moment that diverts Adelio’s attention away from the thermos flasks of ice cream wrapped in towels. The utter stillness, the empty churning of the sea, the singing heat and a jewelled lizard moving with jerky prehistoric tread over the scarred stonework: all conspire to produce a reflective melancholy. There is no need to mention the great army at present camped over the horizon. Instead Jayjay observes how often this piece of apparently deserted terrain has been the scene of battles; that only a year after Nelson defeated the French fleet in this very bay Napoleon won a land battle at Abu Qir when in turn he defeated an Ottoman Turkish force that outnumbered his men by more than two to one. Adelio gazes around at the empty landscape as it simmers and trembles in the heat.