Low & Slow: Master the Art of Barbecue in 5 Easy Lessons (25 page)

Read Low & Slow: Master the Art of Barbecue in 5 Easy Lessons Online

Authors: Colleen Rush,Gary Wiviott

BOOK: Low & Slow: Master the Art of Barbecue in 5 Easy Lessons

4.34Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

To hone this skill, start making mental notes about the relationship between the pile of charcoals and the temperature on the oven thermometer whenever you open the cooker to check the water pan or charcoal level. As I’ve already preached, I’m not obsessive about temperature. The number on the thermometer can waver between 225°F and 275°F throughout a cook. But a combination of the temperature and the condition of the charcoal pile can tell you a lot.

LOW TEMP + LOW, BURNED-UP CHARCOAL:

Add a fresh batch of lit charcoal.

Add a fresh batch of lit charcoal.

LOW TEMP + LOW, RED-HOT CHARCOAL:

Add a fresh batch of unlit charcoal.

Add a fresh batch of unlit charcoal.

LOW TEMP + HIGH, PARTIALLY BURNING CHARCOAL:

The fire is choking. Check the vents for ash or stray charcoal blocking the openings.

The fire is choking. Check the vents for ash or stray charcoal blocking the openings.

HIGH TEMP + LOW, RED-HOT CHARCOAL:

Too much air is circulating over the coals or the water pan is low. Refill the water pan and check the vents to make sure they are closed to the right degree for your cooker.

Too much air is circulating over the coals or the water pan is low. Refill the water pan and check the vents to make sure they are closed to the right degree for your cooker.

HIGH TEMP + HIGH, RED-HOT CHARCOAL:

The water pan is low, the vents need to be closed by one third, or there’s too much charcoal on the pile.

CONTINUING EDUCATIONThe water pan is low, the vents need to be closed by one third, or there’s too much charcoal on the pile.

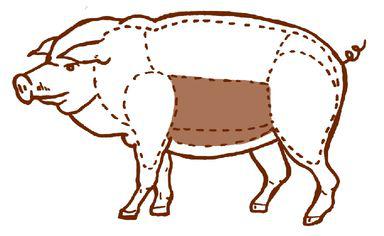

SPARE RIBS ARE THE BRUISERS OF PORK RIBS—

they’re the rack you want on your side in a bar fight and the one you don’t want to meet in a dark alley. The ribs come from the belly of the pig, a.k.a. bacon country, and are bigger, tougher, and fattier than a rack of baby backs. It’s what you serve when the real eaters in your crowd are coming over for dinner.

they’re the rack you want on your side in a bar fight and the one you don’t want to meet in a dark alley. The ribs come from the belly of the pig, a.k.a. bacon country, and are bigger, tougher, and fattier than a rack of baby backs. It’s what you serve when the real eaters in your crowd are coming over for dinner.

The meat on a spare rib needs a longer smoke in order to turn the tough connective tissue and layers of internal fat into unctuous, pork perfection. Because the meat spends more time on the cooker and it’s laced with fat, these ribs can (and should) be seasoned more aggressively, whether you use a dry or wet rub. Seasonings tend to mellow in low and slow cooks, and you want a flavor that can cut through the rich, fatty meat. Keep this in mind when you’re choosing seasonings to make your own rub.

BUYING GUIDETHINK OUTSIDE THE SUPERMARKET.

Independent butchers, retail meat lockers, and food clubs like Sam’s Club and Costco tend to have better butchers, better-quality meat, and a better price.

Independent butchers, retail meat lockers, and food clubs like Sam’s Club and Costco tend to have better butchers, better-quality meat, and a better price.

DON’T BUY WHAT YOU CAN’T SEE.

With loose slabs of ribs or racks vacuum-sealed in clear plastic, you can inspect the condition and cut of the meat. Bulk boxes of ribs may include odds and ends of trimmings or poor cuts you don’t want.

With loose slabs of ribs or racks vacuum-sealed in clear plastic, you can inspect the condition and cut of the meat. Bulk boxes of ribs may include odds and ends of trimmings or poor cuts you don’t want.

CHECK THE TRIM.

Ideally, you want untrimmed spare ribs, but most supermarkets trim the tips and brisket bone and package the racks as St. Louis–style ribs.

Ideally, you want untrimmed spare ribs, but most supermarkets trim the tips and brisket bone and package the racks as St. Louis–style ribs.

AVOID SHINERS.

If you can see rib bone “shining” through the meat, it’s been over-trimmed and signals poor butchering.

If you can see rib bone “shining” through the meat, it’s been over-trimmed and signals poor butchering.

INSPECT THE FAT AND MEAT.

You want even white streaks of fat running through the meat. Avoid (or trim) racks with big patches of fat. Don’t buy a rack with dark spots or dry edges.

You want even white streaks of fat running through the meat. Avoid (or trim) racks with big patches of fat. Don’t buy a rack with dark spots or dry edges.

SAY NO TO “ENHANCED” RIBS.

These racks are treated with saltwater, flavoring, and other preservatives that can make the ribs too salty.

These racks are treated with saltwater, flavoring, and other preservatives that can make the ribs too salty.

CHECK THE WEIGHT.

“3½ down” refers to trimmed racks of spare ribs under 3½ pounds—the ideal weight, according to some pitmasters. We’re using untrimmed racks, which can weigh up to 6 pounds. Heavier racks can indicate an older animal and tougher meat. One slab serves 3 to 4 people.

“3½ down” refers to trimmed racks of spare ribs under 3½ pounds—the ideal weight, according to some pitmasters. We’re using untrimmed racks, which can weigh up to 6 pounds. Heavier racks can indicate an older animal and tougher meat. One slab serves 3 to 4 people.

RIB-TIONARYSPARE RIBS:

A whole section of ribs cut from the belly, with tips still attached.RIB TIPS:

Belly-side strip of cartilage and meat on spare ribs.ST. LOUIS–STYLE:

Spare ribs with rib tips trimmed off.KANSAS CITY–STYLE:

Spare ribs with rib tips and the “skirt” of flap meat trimmed from the bone side.

YOUR FAVORITE CARNIVORES

will delight at the sight of big, meaty slabs of untrimmed spare ribs piled high on a cutting board, but sometimes you’ve got to dish out a classier spread to help convert the shy and picky eaters. Here’s how to put a party dress on your pig.

will delight at the sight of big, meaty slabs of untrimmed spare ribs piled high on a cutting board, but sometimes you’ve got to dish out a classier spread to help convert the shy and picky eaters. Here’s how to put a party dress on your pig.

1. Remove the membrane (page 125).

2. Trim off the triangular “points” on both ends of the spare ribs, leaving ½ to 1 inch of meat from the first bone on either side.

3. Cut off the rib tips at the line of fat that runs horizontal to the bones. (Don’t throw the rib tips away! Season the tips and throw them on the cooker at the same time as the ribs. Tips are the chef’s snack, and the early tasting will let you know if you need to re-season the racks at the end of the cook.)

4. Trim off the hanging flap of meat and any patches of fat or tough sinew.

ONCE THE SPARES ARE OFF THE COOKER,

you can cut and serve the ribs several ways.

you can cut and serve the ribs several ways.

HOLLYWOOD CUT:

Cut flush against the inner side of the first bone on both sides of the rack. Skip the second bone and cut flush against the outer side of the third bone. Repeat. You’ll end up with several rib bones with meat on both sides, as well as a few ribs stripped of meat. The big, double-meaty, flashy ribs are to serve. The stripped bones and ends are chef’s treats.

Cut flush against the inner side of the first bone on both sides of the rack. Skip the second bone and cut flush against the outer side of the third bone. Repeat. You’ll end up with several rib bones with meat on both sides, as well as a few ribs stripped of meat. The big, double-meaty, flashy ribs are to serve. The stripped bones and ends are chef’s treats.

COMPANY CUT:

Cut the racks so that there are three bones per serving; then slice between each rib bone, about three quarters of the way through. The ribs will stay attached, so eaters still get the satisfying, visceral tug of pulling the meat apart.

Cut the racks so that there are three bones per serving; then slice between each rib bone, about three quarters of the way through. The ribs will stay attached, so eaters still get the satisfying, visceral tug of pulling the meat apart.

FINE CHINA CUT:

Slice down the middle of the meat between each rib, all the way through. Each rib will be separate and easy to handle—a meaty, yet delicate serving (if such a thing exists in barbecue ribs) for your refined Aunt Hildred to nibble.

Slice down the middle of the meat between each rib, all the way through. Each rib will be separate and easy to handle—a meaty, yet delicate serving (if such a thing exists in barbecue ribs) for your refined Aunt Hildred to nibble.

HUNGRY MAN CUT:

Toss a full rack of ribs on the table before each hungry, snarling fellow. Move quickly, or risk losing a finger. Have a garden hose ready for cleanup.

CURSES! FOILED AGAIN.Toss a full rack of ribs on the table before each hungry, snarling fellow. Move quickly, or risk losing a finger. Have a garden hose ready for cleanup.

THE QUESTION OF WHETHER OR NOT TO

wrap ribs in aluminum foil pops up frequently on barbecue forums, so let me address it here and now: foiling is for weenies. Foiling is often associated with the 3-2-1 method: three hours bare on the cooker, two hours wrapped in foil on the cooker, one hour unwrapped. The foil traps in steam and juices, so the ribs are braised and steamed in their own liquid. This cuts the cooking time and the amount of charcoal you use. The foil also “protects” the meat from absorbing too much smoke, and it keeps the exterior of the ribs from getting too dark.

wrap ribs in aluminum foil pops up frequently on barbecue forums, so let me address it here and now: foiling is for weenies. Foiling is often associated with the 3-2-1 method: three hours bare on the cooker, two hours wrapped in foil on the cooker, one hour unwrapped. The foil traps in steam and juices, so the ribs are braised and steamed in their own liquid. This cuts the cooking time and the amount of charcoal you use. The foil also “protects” the meat from absorbing too much smoke, and it keeps the exterior of the ribs from getting too dark.

To this, I have four responses. First, you’re making barbecue ribs, not braised ribs. By definition, that means cooking with a clean, controlled charcoal and wood fire, and if you follow the tenets of this program, you won’t need “cheats” like foil to make tender, perfect ribs. Braised ribs also have a mealy, unappealing texture. Second, in case the title of the book didn’t give it away, this is low and slow cookery. Making beautiful barbecue takes time. If you want a shortcut, throw the ribs in the microwave or boil them. Third, are you really worried about the extra $2.50 you might blow in charcoal doing the cook properly? And fourth, you don’t have to worry about over-smoking if you use the KISS setup and follow the instructions for the cook—using the right number of wood chunks or splits (not chips) and maintaining a clean, controlled fire.

MORE RUBS AND SAUCESMOST BARBECUE RUBS AND SAUCES

can be used on any type of ribs (or chicken, for that matter), but I tend to turn up the heat or choose stronger flavors when I’m making blends specifically for spare ribs. Big, bold flavors are right at home on meaty spare ribs, and the longer cook and the all-around fatty goodness of the ribs have a mellowing effect on even the most aggressive seasonings on the meat.

This is my signature rub—the recipe I’m asked for most often and the one I’m most protective of. To be honest, my version never stops evolving. Sometimes I add pequín chile and habañero powder to amp up the heat. I’ll add cumin, coriander, and turbinado sugar if I’m making beef ribs. Lemon zest in the mix works well on chicken, and ground sage goes in if I’m making pork. In other words, this is a highly futz-able rub. This recipe yields a big batch of rub, but I think you’ll find many other uses for it, including Lesson #5. I throw it into everything, including dips, mayo, and salad dressing. Shameless self-promotion: The rub is also available online through The Spice House. I like to use a blend of my favorite dried, ground Mexican chili peppers. I recommend toasting and grinding whole, dried peppers instead of using the store-bought powder, or you can substitute two tablespoons of the Toasted Mexican Pepper Blend (page 18).

MAKES ABOUT 2½ CUPS

Other books

Sisters of the Quilt Trilogy by Cindy Woodsmall

Love Me Always (I Hate You...I Think) by Davis, Anna

Amelia by Siobhán Parkinson

More Stories from the Twilight Zone by Carol Serling

That Awful Mess on the via Merulana by Carlo Emilio Gadda

With Everything I Am by Ashley, Kristen

Affliction by S. W. Frank

The River by Beverly Lewis

Her Cowboy Knight by Johnna Maquire

Brittle Shadows by Vicki Tyley