Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (17 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Koechlin was anxious to hear how Monet was coping with the war. He hoped that, despite everything, he had been able to carry through on his water lilies project: “I hope you’ll be able to describe to me a dining room encircled by water with the lilies on the walls floating up to eye-level.”

26

This vision of the paintings was very much in keeping with Monet’s hope, expressed in 1909, that he could install a “flowery aquarium” in a domestic setting to provide a tranquil oasis. However, Monet’s reply to Koechlin revealed a larger ambition. He explained that he had recommenced work even though he felt ashamed to be painting when so many people were suffering and dying. “But it’s true that moping changes nothing. Therefore,” he told Koechlin, “I’m pursuing my idea of a Grande Décoration.”

This letter marks the first time Monet referred to his project by this resounding name—one that indicated aspirations enhanced beyond a set of dining room walls. “It’s a big project to undertake,” he admitted to Koechlin, “especially at my age, but I don’t despair of finishing as long as my health holds. As you have guessed, it’s the project I’ve had in mind for a long time already: water, water lilies and plants spread across a very large surface.” He closed by inviting Koechlin to come to Giverny to observe the state of his work.

27

Monet’s use of this new term, “Grande Décoration,” which he pointedly capitalized, was intended to pique the interest of Koechlin, a respected art historian and administrator whose specialty happened to be the decorative arts. He served on the council of the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, an association that supported and aimed to improve France’s industrial arts. He had been one of the prime movers behind the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, founded in 1882 and relocated in 1905 to the Pavillon de Marsan in the Louvre. This museum brought together for public display the finest fruits of France’s industrial arts: Sèvres porcelain, Gobelins tapestries, laces and bonnets once owned by the Empress

Marie-Louise, and books from defunct aristocratic libraries. There were also many exhibits from the East: ivories, goblets, and carpets, as well as a Japanese sword and prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige that had been donated by Koechlin himself. It staged an annual exhibition of Japanese prints, and before the war it had mounted a show of something else dear to Monet’s heart: French gardens.

28

Also on display in the museum were huge decorative murals by nineteenth-century French painters. All of them had originally been executed for prestigious locations such as the Tuileries, the Élysée Palace, and the grand salons of sundry spectacular châteaus. Two of the painters with work on conspicuous display in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Jules Chéret and P.-V. Galland, had executed murals for the Hôtel de Ville in Paris. It was a project that Monet knew all too well, because on two separate occasions, in 1879 and again in 1892, his name had gone forward for this very job—both times unsuccessfully.

29

Furnishing important public buildings with

grandes décorations

had long been regarded as the most noble and illustrious role for painting. “Real painting,” exclaimed Théodore Géricault a century earlier, “means painting with buckets of color on hundred foot walls.”

30

His onetime protégé Eugène Delacroix had heartily concurred, deploring the artistic decline caused by small easel paintings and celebrating instead “the magnificent decorations of temples and palaces...in which the artist traces on the wall with the expectation that his expression will be eternal.”

31

Delacroix was the most prolific muralist of the nineteenth century, having spent a good part of his career covering the walls and vaults of important public spaces with inspiring allegories and bloody battle scenes. The Palace of Versailles, the Palais-Bourbon, the Luxembourg Palace, the Gallery of Apollo in the Louvre, the Hall of Peace in the Hôtel de Ville – the politicians and potentates of France could scarcely raise their eyes to the heavens anywhere in Paris without encountering one of Delacroix’s large-scale decorations. These commissions were not only tangible marks of the state’s official favor—what the grateful Delacroix himself called its “flattering distinction”

32

—but also testimony to his vast ambition.

A generation later, Manet’s friend Gustave Doré, an engraver, regarded muralists with little esteem. He used to insult his artistic opponents by saying: “Shut up, you’re nothing but a decorator!”

33

Degas and Pissarro had been contemptuous of murals, but Manet and some of the other Impressionists—and then, as the century turned, Post-Impressionists such as Maurice Denis and Édouard Vuillard—were as enthusiastic as Delacroix. The Impressionists may have made their names with smallish canvases and portable easels that they carried into the fields and forests, but that did not mean none of them dreamed of painting with buckets of color on hundred-foot walls. In 1876, Renoir had lobbied the government’s Fine Arts administration for a public mural commission, and in 1879 Manet had tried, like Monet, to secure the Hôtel de Ville commission. Neither met with success, and indeed none of the Impressionists made their marks with large murals in grand public spaces.

*

In 1912 the poet and critic Gustave Kahn pointed out in an article in a French newspaper the painful but undeniable fact that Impressionism had never been given the opportunity to express its decorative abilities “on the great walls of a palace of State.”

34

Monet with his undoubted decorative abilities seemed the obvious choice for such a commission. In 1900 a curator at the Louvre had written: “If I were a millionaire—or a Minister of Fine Arts—I would ask Monsieur Claude Monet to decorate some huge festival gallery in a People’s Palace for me.”

35

But no millionaires or ministers had stepped forward.

Nonetheless, Monet’s ambitions for his paintings were beginning to stretch beyond his and Clemenceau’s original vision of a domestic setting. He was aiming instead, it appears, at a larger and more public venue—one that would allow his paintings, his Grande Décoration, to cover a “very large surface.” The question was where and how a compliant millionaire or minister could be found in the dark days of 1915, and whose walls would be vast enough to hold these mighty decorations.

*

THE FORLORN MOOD

of the Monet home persisted through the winter. “We live here without seeing a living soul,” he wrote in February. “It’s not particularly cheerful.”

36

Nonetheless, Blanche was still at his side, and Michel remained with him in Giverny, not yet having been mobilized—“which pleases me,” Monet wrote, “because he’ll avoid the cold days of winter.”

37

The horrors of the trenches in winter were one of the many things provoking the wrath of Clemenceau. “Our soldiers are cold,” he thundered in a letter, “and have not been given blankets or gloves or sweaters or warm underwear.”

38

Monet’s mood was always closely related to the progress of his work, and the solitude of Giverny was at least conducive to painting. “I’m not creating miracles,” he informed a friend in February, “and I’m wasting a lot of paint. But this absorbs me enough that I don’t think too much about this ghastly, appalling war.”

39

In fact, his work was sufficiently advanced by the end of the month for him to contact Maurice Joyant, a gallery owner in Paris, asking for the exact dimensions of his premises. The fifty-year-old Joyant, known as “Momo,” had been a close friend of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, exhibiting his paintings (Joyant’s gallery hosted a major Toulouse-Lautrec retrospective in 1914) and sharing with him an interest in food (he would later publish a cookery book with their joint collection of recipes). Momo ran a gallery on the Right Bank with his partner, an Italian printmaker named Michele Manzi.

Le Figaro

commended these two “men of taste” for taking such an active part “in the struggles of the modern schools.”

40

In the summer of 1912 and again in 1913 they staged large Impressionist exhibitions, with Monet prolifically represented on both occasions.

Monet’s reason for contacting Momo stemmed from the fact that two years earlier, in February 1913, the Galerie Manzi-Joyant had hosted an exhibition billed as “a large exhibition of decorative art, featuring all the artists who brought into modern art a note that was new and original.”

41

The reviewer for

Le Figaro

rhapsodized over the sumptuous display; everything from ceramics and Lalique glassware to Gobelins textile designs and grand state-sponsored murals—a whole treasure trove, in

other words, of belle époque decorations and furnishings. “Never have artists with greater skill,” wrote the reviewer, “created such rich and beautiful objects for collectors both now and to come. Never has there been a greater preoccupation with creating for their homes such original and harmonious decorations.”

42

Among the artists whose paintings were featured in the exhibition was Monet, along with Degas and Renoir. The reviewer for

Le Figaro

expressed his regret, like Gustave Kahn a year earlier, at what might have been had these masters of Impressionism been used more productively as decorators. One of the great successes of the exhibition, it could not have escaped Monet’s notice, was Gaston de La Touche, an old friend of Manet and Degas. La Touche had produced murals, in a timidly Impressionist style, for the Élysée Palace and the Ministry of Agriculture; and Raymond Poincaré and his wife “lingered for a long time” before these grand state-sponsored decorations during their visit to the exhibition.

43

Joyant had been hoping to stage an even larger exhibition of decorative art in 1916, but the war had scuttled that plan. For Monet, however, an opportunity presented itself, hence the query to Momo regarding “the exact dimensions of your gallery, length and width. When I come to Paris,” Monet tantalized him, “I shall tell you why.”

44

Monet’s solo exhibitions ordinarily took place at the Galerie Durand-Ruel, whose proprietor, Paul Durand-Ruel, by now eighty-four years old, had faithfully supported and promoted the Impressionists since the 1870s, sometimes at great financial cost to himself. “He risked bankruptcy twenty times to support us,” Monet later remembered.

45

Durand-Ruel’s gallery was found in the rue Laffitte, which was known because of the proliferation of galleries as

la rue des tableaux

(street of pictures). It was, coincidentally, a few doors away from the house in which Monet had been born (“a possible sign of predestination,” according to Clemenceau).

46

Here Monet had exhibited his wheat stack paintings in 1891, his poplars in 1892, his views of Rouen Cathedral in 1895, his paintings of the Thames in 1904, and his waterscapes in 1909. Durand-Ruel was, in addition, the man who financed Monet’s move to Giverny in 1883

and then, in 1890, his purchase of Le Pressoir. As Monet had told an interviewer at the end of 1913: “It would take a special study to explain the role played by this great merchant in the history of Impressionism.”

47

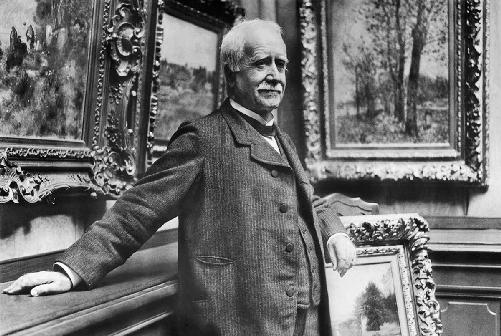

The art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel in his gallery.

Yet Monet was anticipating a different venue for the unveiling of his latest paintings. Evidently the dimensions of the Galerie Durand-Ruel, which had only shown his smaller canvases, he judged inadequate for mounting a display of his Grande Décoration. He may also have found the lighting inadequate: Louis Vauxcelles, touring Monet’s purpose-built studio in 1905, noted that “the light is so much better than in the dungeons of Durand-Ruel’s gallery.”

48

Monet had plainly been making rapid progress since his foray into the cellar with Clemenceau only ten months earlier. Indeed, this new cycle of paintings appeared to be approaching some sort of completion. Even so, in February 1915 it was incredibly audacious, if not blatantly impractical, to envisage staging a solo exhibition of major new paintings—and paintings of a lily pond at that, ones that had been executed

(as he told everyone) as a distraction from the anxieties of wartime at a time when, he acknowledged, other Frenchmen were suffering and dying. How ready the French public might be for poetic glimpses of a water feature in rural Normandy was surely open to doubt.

MONET MAY NOT

have been planning to exhibit his Grande Décoration with Paul Durand-Ruel, but he did have another use for this self-sacrificing and indefatigably supportive businessman. Since the panicky days at the end of August, Monet had been dunning Durand-Ruel and his son Joseph for money: payment from their sales of his paintings. When his first request bore no results, he wrote more pointedly in November, asking Joseph to give him “at least a portion of what you have already owed me for some time already.” The time might well come, he claimed, “when I’ll be strapped for cash.” Joseph no doubt could foresee a time when he, too, might be strapped for cash; nonetheless, he responded quickly, and before a week had passed Monet received a check for 5,000 francs. Monet duly thanked him but added meaningfully in a P.S.: “I took note of your promise to give me other payments when you can.” Another payment arrived the following spring, at the beginning of April, when Durand-Ruel generously stumped up 30,000 francs.

49

This was a large sum, roughly equivalent to the annual salary and expenses of a senator. Durand-Ruel could ill afford such largesse at a time when the art market was depressed because of the war. But Monet, by the spring of 1915, had big plans for spending his money.